Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Thomas Chimes at Art Museum (second review)

In the presence of a great artist

ANNE R. FABBRI

What’s a Greek kid from Elfreth’s Alley, born in 1921, doing getting hooked on Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), a French Symbolist writer famous for his scandalous play Ubu Roi? Now Thomas Chimes is on the mountaintop of his art, and we’re all down below trying to figure it out.

His current 50-year retrospective, “Thomas Chimes: Adventures in Pataphysics," was organized by Michael Taylor, the Art Museum’s curator of modern art. More than 100 paintings, metal box constructions and works on paper created by Chimes from 1959 to 2006— some never seen before— invite us to share his journey through life, thumbing his nose at the world and making art that will survive all of us. The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue with an essay by the curator. Additional recent Chimes works are on exhibition at the Locks Gallery, introducing a new direction for the artist and cause for celebration. And more is still to come.

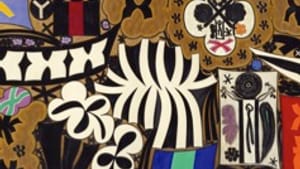

At the entrance to the museum exhibition we are greeted with a colorful, horizontal oil painting on canvas, Mural (1963-65, 83 x 213 inches), on loan from the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida. It began as a Crucifixion scene; now it’s an homage to the new art in France in the first half of the 20th Century, including Matisse-inspired patterns and high value colors, Rouault’s forms and dense black markings, plus the remnants of a presumed figure on a cross (at least, the arms and hands indicate such ). Another cloverleaf enclosure repeats the tragic motif. Despite the jazz beat of the composition, colorful flags in the lower right offer the only promise of hope.

Finding his own voice in Philadelphia

Colorful preparatory sketches and drawings for this mural painting begin the exhibition and, for me, were the most surprising works in the show. Thick licks of yellows in a modernist tempo shout Van Gogh. With these paintings, Chimes was part of the post-World War II New York Art League coterie, and he was making it, (two of his paintings were purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in 1961 and ’63). However, Chimes moved back to Philadelphia in 1953 and began to find his own voice instead of being just part of the chorus.

The next gallery reveals a totally different Chimes, one who expresses himself and no one else. For the next ten years Chimes utilized his expertise as an aircraft mechanic to create mixed metal box constructions of subtly shaded metallic surfaces with knobs and compartments that seemed destined to house something pure and indefinable. Some contained haunting portraits; others abstract symbolic shapes. They exude an eerie presence, vitality confined within bounds. They look as if they should be one surface of a solid form that has some useful purpose. But since when does art need such an excuse for being?

Waiting for the axe to fall

Having explored this facet of non-objective art, Chimes moved on in the 1970s to create a pantheon of portraits based on old, sepia photographs of 19th Century literary figures, primarily French Symbolists who were part of the circle of Alfred Jarry, his new consuming interest. Their overall brown tonality and heavily grained wood frames could be derived from Eakins’s portraits, but that seems to me to be a glib interpretation of Chimes’s persona. I think he used the apparent imagery and palette of the 19th Century bourgeois sense of decorum to create his own esoteric symbols based on eroticism. Then he waited for the axe to fall, but it never did. The portraits were valued for what they seemed to be, not what they were. Look closely; see what you think.

Suddenly, everything changed in the 1980s. Chimes abandoned portraits of dead heroes, stripped away color and, working in a larger format, abandoned himself to visualizing life as his alter ego, Alfred Jarry, and his infamous creation, King Ubu. Jarry’s Pataphysics satirized the contemporary fascination with science and paraphrases its logical explanations for everything. These are haunting paintings, often beginning as a landscape, then eliminating the sky and horizon. We see a figure on a bicycle, then the bicycle disappears, the figure fades and only the head and hat remain. Others begin as landscapes of Philadelphia, with Memorial Hall pared down to a dome— or is it a breast with a protruding nipple, possibly expressing a mid-life masculine longing for the testosterone of his youth when everything is referenced by eroticism? These are paintings of no man and every man in the solitude of his life’s journey.

Like the last sentence of Finnegan’s Wake

Chimes then eliminates every possible redundancy including size and color. His final work in the Art Museum exhibition is Untitled (Finnegan’s Wake), 2000-2006, a group of 25 oil paintings on panels measuring three by three inches. Each panel contains a different figure or symbol from his earlier work, a reprise of the album of his life. Nothing extraneous remains. Nothing is lost. Like the last sentence of Finnegan’s Wake, it begins again…

The Chimes exhibition at the Locks Gallery includes some 50 small works, series of up to ten panels, installed in sequence. Chimes describes them as visual poems summing up the imagery of his past works. The NtroP series, numbered by the artist according to the number of panels in that specific series, transforms images into portraits, like ancient coins revealing the gilt on their raised edges. His portraits are here as well as the mystical numbers found in alchemy journals, and even the Crucifixion images, many of them displaying a new technique of raised lines defining the forms. Grouped in sequences of these small images, lacking all color and any decorative references, the effect is magical, the sense of presence of a great artist. We are fortunate to be able to claim him for the Philadelphia pantheon, but his art belongs to the world.

Chimes commented on his life’s work in Homeric terms, responding to a bystander, “Why are you weeping, stranger? The gods arranged all this destruction; what remains is the song.”

Tio read a response, click here.

To read another review by Andrew Mangravite, click here.

ANNE R. FABBRI

What’s a Greek kid from Elfreth’s Alley, born in 1921, doing getting hooked on Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), a French Symbolist writer famous for his scandalous play Ubu Roi? Now Thomas Chimes is on the mountaintop of his art, and we’re all down below trying to figure it out.

His current 50-year retrospective, “Thomas Chimes: Adventures in Pataphysics," was organized by Michael Taylor, the Art Museum’s curator of modern art. More than 100 paintings, metal box constructions and works on paper created by Chimes from 1959 to 2006— some never seen before— invite us to share his journey through life, thumbing his nose at the world and making art that will survive all of us. The exhibition is accompanied by an illustrated catalogue with an essay by the curator. Additional recent Chimes works are on exhibition at the Locks Gallery, introducing a new direction for the artist and cause for celebration. And more is still to come.

At the entrance to the museum exhibition we are greeted with a colorful, horizontal oil painting on canvas, Mural (1963-65, 83 x 213 inches), on loan from the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida. It began as a Crucifixion scene; now it’s an homage to the new art in France in the first half of the 20th Century, including Matisse-inspired patterns and high value colors, Rouault’s forms and dense black markings, plus the remnants of a presumed figure on a cross (at least, the arms and hands indicate such ). Another cloverleaf enclosure repeats the tragic motif. Despite the jazz beat of the composition, colorful flags in the lower right offer the only promise of hope.

Finding his own voice in Philadelphia

Colorful preparatory sketches and drawings for this mural painting begin the exhibition and, for me, were the most surprising works in the show. Thick licks of yellows in a modernist tempo shout Van Gogh. With these paintings, Chimes was part of the post-World War II New York Art League coterie, and he was making it, (two of his paintings were purchased by the Museum of Modern Art in 1961 and ’63). However, Chimes moved back to Philadelphia in 1953 and began to find his own voice instead of being just part of the chorus.

The next gallery reveals a totally different Chimes, one who expresses himself and no one else. For the next ten years Chimes utilized his expertise as an aircraft mechanic to create mixed metal box constructions of subtly shaded metallic surfaces with knobs and compartments that seemed destined to house something pure and indefinable. Some contained haunting portraits; others abstract symbolic shapes. They exude an eerie presence, vitality confined within bounds. They look as if they should be one surface of a solid form that has some useful purpose. But since when does art need such an excuse for being?

Waiting for the axe to fall

Having explored this facet of non-objective art, Chimes moved on in the 1970s to create a pantheon of portraits based on old, sepia photographs of 19th Century literary figures, primarily French Symbolists who were part of the circle of Alfred Jarry, his new consuming interest. Their overall brown tonality and heavily grained wood frames could be derived from Eakins’s portraits, but that seems to me to be a glib interpretation of Chimes’s persona. I think he used the apparent imagery and palette of the 19th Century bourgeois sense of decorum to create his own esoteric symbols based on eroticism. Then he waited for the axe to fall, but it never did. The portraits were valued for what they seemed to be, not what they were. Look closely; see what you think.

Suddenly, everything changed in the 1980s. Chimes abandoned portraits of dead heroes, stripped away color and, working in a larger format, abandoned himself to visualizing life as his alter ego, Alfred Jarry, and his infamous creation, King Ubu. Jarry’s Pataphysics satirized the contemporary fascination with science and paraphrases its logical explanations for everything. These are haunting paintings, often beginning as a landscape, then eliminating the sky and horizon. We see a figure on a bicycle, then the bicycle disappears, the figure fades and only the head and hat remain. Others begin as landscapes of Philadelphia, with Memorial Hall pared down to a dome— or is it a breast with a protruding nipple, possibly expressing a mid-life masculine longing for the testosterone of his youth when everything is referenced by eroticism? These are paintings of no man and every man in the solitude of his life’s journey.

Like the last sentence of Finnegan’s Wake

Chimes then eliminates every possible redundancy including size and color. His final work in the Art Museum exhibition is Untitled (Finnegan’s Wake), 2000-2006, a group of 25 oil paintings on panels measuring three by three inches. Each panel contains a different figure or symbol from his earlier work, a reprise of the album of his life. Nothing extraneous remains. Nothing is lost. Like the last sentence of Finnegan’s Wake, it begins again…

The Chimes exhibition at the Locks Gallery includes some 50 small works, series of up to ten panels, installed in sequence. Chimes describes them as visual poems summing up the imagery of his past works. The NtroP series, numbered by the artist according to the number of panels in that specific series, transforms images into portraits, like ancient coins revealing the gilt on their raised edges. His portraits are here as well as the mystical numbers found in alchemy journals, and even the Crucifixion images, many of them displaying a new technique of raised lines defining the forms. Grouped in sequences of these small images, lacking all color and any decorative references, the effect is magical, the sense of presence of a great artist. We are fortunate to be able to claim him for the Philadelphia pantheon, but his art belongs to the world.

Chimes commented on his life’s work in Homeric terms, responding to a bystander, “Why are you weeping, stranger? The gods arranged all this destruction; what remains is the song.”

Tio read a response, click here.

To read another review by Andrew Mangravite, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.