Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

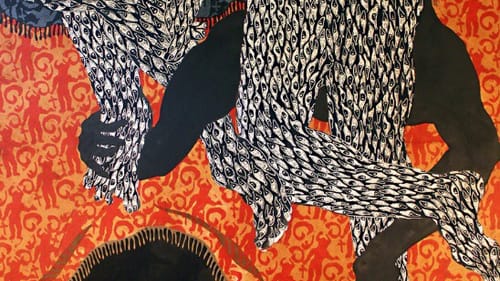

Art of the archipelagos

The Delaware Art Museum presents ‘Relational Undercurrents’

The Delaware Art Museum just opened the thought-provoking Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago. Both striking and challenging, the exhibition features 50 wildly different artists who explore the rich cultures of island nations trampled by colonizers (from conquerors to tourists) and buffeted by weather and global politics.

All these works were created in the 21st century and—like the 17 countries they represent and illuminate—span geography and genres to elicit strong responses. Strikingly curated by Tatiana Flores and organized by California’s Museum of Latin American Art, the exhibition challenges cultural tropes via fecund messages that bubble up from visual first impressions.

Impossible to contain

Though it’s centered in the museum’s largest gallery, Relational Undercurrents literally cannot be contained. Just as it encompasses many countries and multiple points of view, the art spills into nearby hallways and gathering spaces. A small gallery has been transformed into an intimate screening room for eight (sometimes uncomfortably visceral) mature-content video artworks.

One of the exhibition hallmarks is that many of these pieces (whether monumental or exceedingly intimate) are at first visually welcoming—seemingly inviting through style, color, whimsy, or familiarity—but they soon deliver much deeper meanings.

Mapping, horizons, representation, and ecologies

Flores explores four themes. “Conceptual Mappings” considers cartography and its attempt to both define and carve up the archipelago. Juana Valdes (Cuba, b. 1963) created Under View of the World (2015), a cyanotype (blue photograph) of the undersides of imported porcelain, to chart colonialism via commodity circulation. And Karlo Andrei Ibana (Puerto Rico, b. 1982) blanked out countries on four small globes with green chalkboard paint for Collective Memory II (2012-19), inviting viewers to create their world while commenting on the erasure of peoples and culture.

“Perpetual Horizons” explores whether the line delineating sky from land and sea—a constant that also shifts—is a source of hope or a limit. A striking oversized digital photograph by Marianela Orozco (Cuba, b. 1973), Horizons (2012), confronts this contradiction: a woman rests her head on outstretched arms, creating a horizon that both embraces and confines her. And three lush photographs (2003) by Jean-Luc de Laguarigue (Martinique, b. 1953) that document the evacuated, sea-eroded town of Nord Plage seem tranquil, but close study reveals their desolation.

“Representational Acts” considers identity—individual, social, and national—in cultures that have withstood colonialism and occupation. Dancing Pouring, Crackling and Mourning (2015) is a huge, vibrant painting by Didier William (Haiti, b. 1983), whose representations of Papa Legba (Haitian deity of the crossroads) create a textile pattern. In Present, Present, Present (2017), Sofía Galisá Muriente (Puerto Rico, b. 1986) made a can’t-turn-away four-channel video installation that documents her country’s “exotic funerals,” with the deceased posed to depict hobbies or favorite activities. Sasha Huber (Switzerland and Haiti, b. 1974) made Shooting Back (2004) with a semiautomatic staple gun and 100,000 staples, a violent creative act that resulted in a surprisingly serene portrait of Christopher Columbus.

“Landscape Ecologies,” the exhibit’s fourth section, features one of its most riveting works. Lost at Sea by Edouard Duval-Carrié (Haiti, b. 1959) is a monumental work on aluminum that disconcertingly references everything from a bleak Gauguin to a painting on velvet. In contrast are three delicate cut-paper collages (2011) by Frances Gallardo (Puerto Rico, b. 1984) that appear to depict white lace or a black mantilla but are actually recreations of hurricanes.

A creative force

Kudos to curator Margaret Winslow and museum preparators who installed this rangy, unconventional exhibition. Artist talks, musical programs, and an African and Caribbean Festival (August 3) are coming up this summer. Gallery guides and wall texts are written in English, Spanish, and Haitian Creole, and tours are also available in all three languages.

From this part of the world, it is all too easy to see the Caribbean as a sunny, single-faceted travel destination, but this exhibition is truly an eye-opener. In Relational Undercurrents, Flores has gathered a trove of gifted artists for a serious reconsideration of this powerfully resilient archipelago and its immense creative forces.

What, When, Where

Relational Undercurrents: Contemporary Art of the Caribbean Archipelago. Through September 8, 2019, at the Delaware Art Museum, 2301 Kentmere Parkway, Wilmington, Delaware. (302) 571-9590 or delart.org.

Museum facilities, entrances, galleries, and parking are all easily wheelchair-accessible, and there are wheelchairs available to borrow at no cost. Visit online for more information on accessibility.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder