Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Before photography was art

The Barnes Foundation presents ‘From Today, Painting Is Dead'

The story (possibly apocryphal) goes that, in 1839, influential French painter Paul Delaroche saw a daguerreotype for the first time and promptly declared, “From today, painting is dead!” He was wrong, but the new photography exhibit at the Barnes Foundation goes a long way toward explaining why the new technology dismayed Delaroche.

From metal to paper

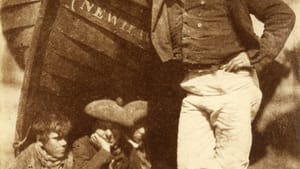

From Today, Painting Is Dead: Early Photography in Britain and France pulls together a wide range of specimens from early 19th-century photographers who were getting a handle on the new technology, learning and exploring the artistic possibilities of this new mass medium. While the artistic mainstream of the time was slow to accept photography as an art form, viewing it with disdain and even hostility, the exhibit shows that the photographers themselves were quick to find their artistic voice.

Drawn exclusively from the vast personal collection of Michael Mattis and Judy Hochberg and curated by Barnes president Thom Collins, the exhibit contains works by more than 60 photographers, from early daguerreotypes (the first photographic process, which used metal plates and was slow and unwieldy) to works by William Henry Fox Talbot, credited with inventing the first photographic prints on paper.

Regulating art

European artists and their art operated under a strict regime in the 19th century. There were rigid guidelines and categories, prioritized by Europe’s fine-arts academies according to artistic merit (and, presumably, profitability). The leading subject category was history/allegory, particularly if it imparted some moral or nationalistic message. Then, in order of priority (or perceived “artistic value”), came portraiture, scenes of daily life (or “genre”), landscapes and, lowest on the ladder, still life.

Photographers of the time worked inside these categories, and Collins has organized the show along those lines. This enables the viewer to discern how, as the technology advanced and the photographers became more adept with the process, their imagery became deeper and more nuanced.

Exposure and color

A perfect example of this development can be seen in landscapes. Early techniques required long exposures of a perfectly still subject, which explains why so many of those early portraits were stiffly posed and why skies were always overexposed and washed out. However, once film came into use and exposures could be controlled, skies could be imaged in great detail. Landscapes with billowing cloudscapes were an instant sensation.

Since the technology for color photography took more time to develop and wasn’t commercially successful until French film and photography pioneers Auguste and Louis Lumière debuted their process in 1907, almost all the photographs in From Today are black and white. This does not pose a problem for the modern eye; today, we are accustomed to black-and-white photography denoting serious “art” photos. The subtle shades of gray and sepia tones lend an air of gravitas to the images, giving them an artistic nuance often lacking in modern color photos of similar subject matter.

French postcards

One of the few exceptions to the all-black-and-white rule is a series of small daguerreotypes by an unknown French photographer of female nudes. These are, of course, examples of the famous French postcards of the 19th century. The color was imparted by paint applied by hand directly onto the metal daguerreotype plates, not an efficient method for mass production. The discreet poses and soft, gauzy colors give the subjects an ethereal Raphaelite quality reminiscent of the old master’s painted works—artful and modest to today’s eye, but considered shameful pornography in its day.

Becoming artists

Every category in the exhibit is filled with gorgeous images that today’s artistic cognoscenti would consider gallery-worthy. However, it would be years before Europe’s academic artistic elite began considering photography a valid art form and not dismissible tripe or commercial fodder for the unenlightened masses.

As is usual with a Barnes exhibit, the educational aspect of the exhibit is as important as the artistic merit of the works on display—which are considerable. Viewers can learn about the artistic milieu of the age and some of what the practitioners of this new medium went through as they struggled to become artists in their own right.

What, When, Where

From Today, Painting Is Dead: Early Photography in Britain and France. Through May 12, 2019, at the Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. (215) 278-7200 or barnesfoundation.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gary L. Day

Gary L. Day