Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The artist's intention

On the third floor of the Pitti Palace Museum in Florence, Italy, I am drawing. For three weeks, I have drawn in various museums throughout Italy, standing in front of a painting or sculpture for such a long time that I am often surprised by the kindness of a guard offering me a chair.

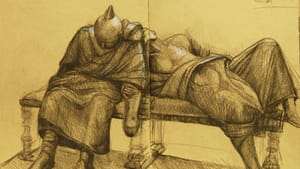

On this particular afternoon, I find myself drawing a life-sized bronze sculpture of two men on a bronze bench, a work by the mid-19th-century artist Achille D’Orsi. I think both men are slaves; they appear to be in an intense state of distress. One of the men is leaning against the other, who is slumped over at the end of the bench. The visual composition is strong, using the horizontality of one slave (who, I assume, is dying) against the verticality of the other (who appears to be comforting him).

Mario, a red-haired, freckled guard, enters the gallery in which I am drawing the two slaves. I ask him about the piece, but he doesn’t understand my question, or I don’t understand his answer. Instead, he asks me to have coffee with him. I decline, not wanting to take time off from drawing. I assume Mario is bored and glad to have a diversion in his workday.

While drawing, my mind wanders to prisons where I often exhibit my art and teach. There too, the guards get bored, but prison guards can be more aggressive. One prison guard asks me if I had sexual affairs outside my marriage. “After all,” he says, “artists are known to be wild.” I merely answer that I am old enough to be his mother, adding, “Even you don’t want to know what Mom does for sex.” He doesn’t respond.

The bronze sculpture of the two slaves at the Pitti Palace reminds me of prison and the kindness that I witness between prisoners.

The kindness of prisoners

While drawing the sculpture, I remember walking across the prison yard with art materials in boxes on a cart, when several prisoners offer to help me. I say, “Thank you,” followed by the obligatory hesitation. As a volunteer art teacher in a high-security prison, I must provide the necessary pause allowing the staff person with me to actually answer the prisoners’ offers of help. “No.” Apparently, we can manage on our own. Further into the prison yard, we meet several more prisoners who are in my class. They, too, offer help and, again, the answer is, “We can manage on our own.” The prisoners do help when we finally reach the front steps of the classroom building because, at that point, neither the staff person nor I can manage carrying the boxes up the stairs.

In this drawing reverie, I think of the prisoner Richie pushing the walker upon which he is dependent. I do not know the cause of his disability. The fact that it is prison makes me assume that Richie’s disability is the result of violence rather than a congenital problem — other than the location, though, I don’t know why I make this assumption. When Richie reaches the stairs to the classroom, he, too, is unable to maneuver up on his own. One prisoner takes Richie’s walker while another lends him an arm to lean upon. This is not the first time I have seen the prisoners helping another prisoner, particularly those with handicaps attempting to traverse this landscape, which is not friendly to anyone. I am struck with the automatic help that is given to Richie. There is no hesitation in the prisoners’ help to Richie, and Richie does not hesitate in accepting it.

Reframing the artwork

In drawing the sculpture on the third floor of the Pitti Palace, I am eventually curious as to whether the sculptural figures fit my associations to prison.

The title, which I hadn’t noticed at first, is The Parasites. To my surprise, I am totally misreading the sculpture. The two men I am experiencing as slaves (and consequently prisoners) are, in fact, drunken Roman revelers — not slaves, but captors; not dying, but sick from overindulgence. The sculpture is part of late 19th-century socialist realism, a statement against capitalistic evils.

My disconnect makes me wonder: “Does the artist’s intention matter?” Or does the viewer’s experience of the work of art take precedent? Does it matter that D’Orsi has a clear intention of propaganda in his art?

I think of the Aeneid and its pro-Augustus propaganda. Does the dimension of indeterminacy in both the D’Orsi sculpture and Virgil’s Aeneid provide space for an aesthetic interpretation rather than a purely rational voice of instruction? And does this interpretative space in both the sculpture and poem enable the dimension of art to take hold, diminishing the prescription of propaganda?

A number of years ago, I had artwork at Art Miami. While standing near one of my monoprints, I overheard a couple describing it as “dark and depressing.” No more than five minutes later, I hear another couple say the opposite: “Oh, the colors are so bright and cheery.” I haven’t a clue whether I intend gloom and doom or happy and bright. I respond to the clues of the landscape or the cues on the paper and do not designate a specific narrative to the work. If the viewer is dependent upon my intention, I have none to offer.

Art presents itself in an excess of meaning, and I am not concerned by D’Orsi’s propaganda. While drawing the bronze sculpture on the third floor of the Pitti Palace in Florence, Italy, there is just Mario the guard talking at me, and I am thinking about the kindness between prisoners.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Treacy Ziegler

Treacy Ziegler