Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Songs of ecstasy and painful longing

Tenor Mark Padmore and pianist Jonathan Biss

But what if pleasure and pain should be so closely connected that he who wants the greatest possible amount of the one must also have the greatest possible amount of the other, that he who wants to experience the "heavenly high jubilation," must also be ready to be "sorrowful unto death"? (Friedrich Nietzsche)

No Romantic composer more fully explored the sturm und drang of pleasure and pain, ecstasy and despair, than Robert Schumann, and this is especially true of his song cycles. As his colleague Franz Liszt said, “Schumann lived equally in the life of poetry and music.” Setting poetry to music gave him the opportunity to explore emotions in an intimate setting in which the words already conveyed depths of feeling and where the composer could use the human voice to transform the words of the heart into music. Tenor Mark Padmore and pianist Jonathan Biss, each a resilient and versatile musician in his own right, possess a common musical sensibility that allowed them to collaborate to maximum effectiveness on two of Schumann’s song cycles, as well as vocal-piano music of two later composers, Michael Tippett and Gabriel Fauré.

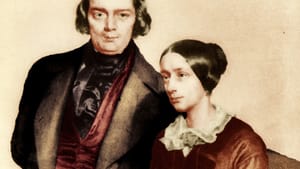

Schumann was a prolific writer of songs, early inspired by Clara Wieck, his beloved wife. Their courtship was disrupted by her father’s objections to the marriage, but love won out. For Schumann, the pleasure and pain of their courtship found words in the poetry of Heinrich Heine, from which Schumann selected nine poems for a Liederkreis (song cycle), Op. 24. The poems depict the alternating agony and ecstasy of one madly in love who knows from the beginning that the love will never be consummated. Schumann gradually built the intensity of the music to where it approaches near madness and utter despair.

Yet, contrasted with the second song cycle on the program, the music of Schumann’s Liederkreis is relatively well-contained. It can be seen, in large part, as an extension of Franz Schubert’s measured approach, in which Schubert produced lieder of such integrity that they have been the gold standard of song cycles ever since. However, ten years after composting Liederkreis, Schumann had developed his own conceptions more fully and was also experiencing increased episodes of a major mental illness, some of which for a time he was able remarkably to sublimate into great music.

During that period, when he had fully developed his own musical identity, he chose for a song cycle the beautiful but nearly deranged poetry of Nikolaus Lenau, a German poet who lived in the United States for a short period, and, back in Germany, eventually succumbed to insanity. Schumann’s Sechs Gedichte und Requiem, Op. 90, took the tortured words of Lenau (“From the silent beam of pain / You bow and turn pale / At your feet, I would like, … / To silently pour my pain out”) and transformed them into complex and intense musical expressions that pressed the limits of the theory and technique of the time.

Twists and turns

Padmore and Biss did amazingly well in communicating this concatenation of musical exploration with a sense of discipline yet with full expression of the emotional twists and turns that both Lenau and Schumann intended, or maybe we should better say, couldn’t help expressing. In any case, as the Lenau-based songs concluded with a consoling “Requiem,” it was apparent that Padmore and Biss had mastered a profound musical challenge, rendering interpretations of great passion and beauty.

The choice of compositions by two later composers, Michael Tippett and Gabriel Fauré, served to illustrate the sea change in the pleasure/pain principle between Romanticism and Modernism in Western life and thought. The Romantics endured pain for the sake of an ideal, while in modern times, pain became an existential requirement for being in the world. Thus, both Tippett’s Boyhood’s End and Fauré’s La Bonne Chanson, Op. 61, are about the paradoxical pain of enduring successful consummations.

Tippett’s poet, William Henry Hudson, got what he “wanted” (the single word “want” in ‘I want only to keep what I had” becomes extended into a rapturous chant), ecstatic recollections of his childhood in Argentina, and Fauré’s Paul Verlaine depicts repeatedly ecstatic encounters with his lover. Yet they both suffer: Hudson from the awareness that his boyhood is gone and Verlaine from an exhausting obsession with his love object. Musically, we have moved in a parallel development from Schumann’s compositions, which revolve around an ideal song form, to those of Fauré (who comes first chronologically, though not in the program) — who composes in an open form in which the poems flow into one another — and Tippett, who writes a “cantata,” which for him goes back well before J.S. Bach.

Tippett’s musical setting is like ascending a craggy mountain of ever-changing sounds, presenting frequent challenges to both singer and pianist, which they handled masterfully. Padmore was especially successful in vocalizing volcanic flows of shifting lava, perhaps Tippett’s way of rebelling against the smoothness of Vaughan Williams and company, as did Tippett’s friend Benjamin Britten, to whom the piece was dedicated and who played piano at the 1943 premiere with his partner Peter Pears singing. Biss negotiated difficult piano passages with a finesse that suggested a mastery of the modern repertoire beyond his long preoccupation with Beethoven, Schubert, and Schumann. What is remarkable about their performance is that they were able to extract the maximum emotional power from the music without exaggeration or sentimentality. And for sheer sound, they are a perfect match, bringing out the exquisite sonorities of which the pianoforte and the human voice are capable.

Another feature of the song form is that, at its best, it capitalizes on the fact that language itself has musical elements. Utterances, phonemes, gutturals, vowels, dialects: These are the “notes” of language, beyond meaning but informing it. To Padmore’s great credit, he made manifest the sheer sonic beauty inherent in language itself.

What, When, Where

Mark Padmore, tenor, and Johnathan Biss, piano. Schumann: Liederkreis, Op. 24; Schumann: Sechs Gedichte und Requiem, Op. 90; Tippett: Boyhood’s End; Fauré: La Bonne Chanson, Op. 6; Encore: Schubert “Serenade.” Philadelphia Chamber Music Society, Perelman Theater, Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, Broad and Spruce Streets, Philadelphia. October 15, 2014. www.pcmsconcerts.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Victor L. Schermer

Victor L. Schermer