Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The human cost of walls

Temple’s Paley Library presents Laura Elizabeth Pohl’s ‘A Long Separation’

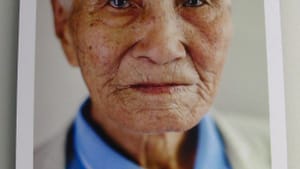

Imagine it being illegal to see your mother, or your brother, or your child. A Long Separation, a traveling photography exhibition currently on view at Temple University, vividly depicts the human cost of political walls — like the story of Jo Jang-keum, who hasn’t seen her sisters since she was a teenager in North Korea, more than 60 years ago.

For Nam Keung-bong, 87, it’s been almost 70 years since he saw his wife and son. Jeon Ju-Eul left his North Korean home on Christmas Day 1950, urged on by his mother, who feared a nuclear bomb would be dropped on their town. He never saw her again.

Photographer and filmmaker Laura Elizabeth Pohl introduces 10 of the thousands in South Korea and the United States who left North Korea a lifetime ago. Now in their 80s and 90s, they’d like to see their relatives before they die. Their hope depends on longevity and luck.

Cold peace

After World War II, the Korean peninsula was arbitrarily divided into communist North Korea and democratic South Korea. The arrangement led to the Korean War (1950-1953), later known as the "Forgotten War." Thousands of North Koreans fled south in the run-up to the conflict, and when it ended, a heavily fortified demilitarized zone and isolated political regime created an impenetrable barrier.

For more than 65 years, that barrier has divided two nations with one culture. North Koreans have not been able to go home, contact relatives they left behind, or return to honor their dead.

“People are not allowed to legally communicate with each other,” Pohl said in an interview last May. “They can’t email. They can’t call. They can’t FaceTime.” She witnessed the anguish of her great-uncle, Yu Il-Sang, who died in 2014. He left home just before the war and never saw his family again, lamenting the loss for the rest of his life.

Few chosen

The only hope for exiles, most in their 80s and 90s, is to apply for infrequent reunions arranged by the North and South Korean Red Cross. Only those living in South Korea are eligible, and attendees are chosen based on age and relationship to those they seek — parents, siblings, and children receive preference.

Pohl interviewed Jo on the day the 82-year-old learned that she had not been chosen for a 2015 reunion. By then she was alone, her husband and only child having died, and she wanted to reunite with her sisters in North Korea, whom she’d not seen since her teens. “My hope is gone,” she told Pohl.

After being on the list for years, Lee Tek-Gu, 90, was chosen for the 2015 reunion. He’d hoped to meet his seven siblings, whom he hadn’t seen since he was 22. Instead, he met two nephews, strangers to him, who brought Lee a picture of his mother (likewise separated from him). “That’s what I got from this meeting,” he told Pohl. “That’s the only thing that I got.”

Reunions are held in border locations and last a few days. About 20 have been held since 2000. The New York Times notes that though roughly 20,000 exiles have been reunited since 1985, thousands more have died waiting. According to the Times, as of August 2018, 56,000 applicants were still waiting.

Preserving family stories

Pohl was determined to increase awareness of the ongoing tragedy by preserving stories like her great-uncle’s. The original exhibit, self-financed by the artist, speaks to her determination. Initially, émigré portraits and captions wrapped the outside of a rented truck, which Pohl last spring drove from Virginia to Massachusetts, parking at prearranged public libraries. (Her first plan, to put the exhibit inside the truck, was not ADA-compliant.)

Among those who assisted Pohl were the South Korean Red Cross, which helped identify exiles willing to talk, and her mother, who was born in South Korea and helped with translation.

A moving presentation

No longer on wheels, A Long Separation is presented simply and accessibly in a well-lit hall of Temple’s Paley Library. Each of 10 close-up portraits is accompanied by English and Korean captions by Pohl summarizing her interviews. Visitors can also listen on cellphones to spoken excerpts.

One of Pohl’s interviewees, Kang Neung-hwan, 94, didn’t know his wife was pregnant when he left North Korea. Father and son finally met in 2014. “What kind of thinking is this?” he said. “They are communists and we are a free country… We are one people… We are the same people, so I wish we can unify quickly. I would like to request that the government work a little faster.”

An undeservedly courteous request in the face of heartless cruelty.

What, When, Where

A Long Separation. By Laura Elizabeth Pohl. Through February 28, 2019, at Temple University’s Samuel L. Paley Library, 1210 Polett Walk, Philadelphia. (215) 204-8212 or library.temple.edu.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.