Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

City living through the eyes of its champion

Robert Kanigel's 'Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs'

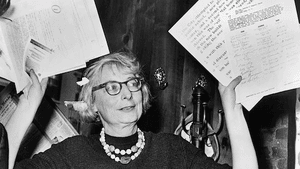

She’s known as “the City Woman.” Jane Jacobs (1916-2006), author and activist, isn’t as well known as she used to be, but in the public's mind, she’s still associated with cities. Robert Kanigel, author of Eyes on the Street: The life of Jane Jacobs, gave an excellent talk last Thursday at a Free Library of Philadelphia author event that filled out Jane’s story in an authoritative and cordial manner.

New admirer and old enemy

Kanigel found Jacobs’s letters to her mother in a stash of papers at the Boston Library. He found them uncommonly smart and pleasant, catalyzing his interest in her.

Although she was a poor student who hated school and never finished college, Jacobs’s intelligence, lucidity, and maverick individuality eventually led her to write the influential The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961). Her book championed small, organic, diverse, spontaneous development of urban neighborhoods over the monotonous sameness that often accompanied urban renewal projects. The ideal was a mix of ordered car-oriented places and “messier” areas.

She is also famous as the enemy of Robert Moses, New York’s city planner. In a contest with the tension of a David and Goliath story, activist Jane stopped a planned expressway intended to go through Lower Manhattan and Greenwich Village, where she resided.

Finding an urban path

In his soft-spoken manner, Kanigel explained how Jacobs found her path. She grew up in in Scranton, Pennsylvania, one of five children. Her father was a doctor, her mother a teacher and nurse. Instead of earning a college degree, Jacobs went to Powell Business School, where she improved her typing and shorthand and learned how to comport herself.

In 1954 she moved to Greenwich Village. The Village was the best example of the glory of a colorful and vital mixed-use neighborhood. She took low-level secretarial and clerical jobs and began to do some writing, including an article for Vogue about four individual neighborhoods in New York City. She also wrote for Architectural Forum and Iron Age. She became friends with a man named Bill Kirk, who disliked the urban renewal occurring in East Harlem that killed off shops and street life.

During Philadelphia’s 1955 redevelopment push, Jacobs wrote a preview of what to expect. When Ed Bacon took her on a tour she asked, “Where are all the people?”

Fighting sterility

This reminds me of the time I asked a Ritz movie theater co-worker if she liked Society Hill. She answered at once, “No, it’s too sterile.” She’s right; it is pretty and historic, but it’s also monotonous.

The Death and Life of Great American Cities is a lengthy tome that took time to fully catch on. It was popular in the 1970s with planners and architects who saw it as a great brief for city living. Sometimes Jacobs was attacked as “just a housewife,” yet she overturned the preconceptions of professional city planners.

Eyes on the Street also refers to the need for people to be up close and observant outdoors to deter misbehavior and crime. No city is exactly paradise.

What, When, Where

Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs. By Robert Kanigel. Alfred A. Knopf, 2016. 496 pages, hardcover; $20.83, available at amazon.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.