Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Forgotten country, forgotten sculptor

Rediscovering Croatia

When my wife proposed that our summer wander would be Croatia this year, I grumbled silently at all the major art shows I could be missing in Munich or Berlin, London or Paris, all easily accessible from my Eurocenter in Weimar. Then I remembered my first Croatian visit, when I cleared my mind from summer teaching in London in 1974: a film festival on animation in the capital Zagreb, not to forget the post mortem of folk dancing in a hill village nearby. Those rural ladies were so beguiling in ignoring my "urbane" fumble stumbling.

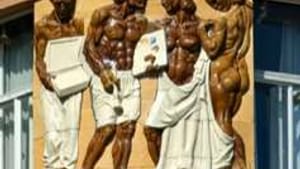

But what finally turned me on was the festival director's enthusiasm for a local celebrity sculptor. Ivan Mestrovic (1883-1962) had left a sizeable collection of his diverse works in stone, wood and metals to the city of Zagreb.

His home in Split is now a major museum on a hill overlooking the Adriatic, a stunning seascape I was to goggle at for hours, after as exhaustive a scrutiny as I have ever given a personal collection (while my wife guided my young son in a naked romp under the sprinkler in the garden between the museum and the sea).

From poverty to Notre Dame

In the museum store I bought Ivan Mestrovic: The Making of a Master, by the sculptor's daughter Maria, as well as a dozen postcards of his work. The book is worthy of the sculptor whom his pal Auguste Rodin ranked alongside Michelangelo. Maria is as adept at describing the harried history of Croatia as she is at describing her father's rise from deep poverty to an internationally celebrated artist in residence at Notre Dame University.

I chattered with the museum's Moldovan young lady curator-manager, who spoke fluent English. She sadly reported that after the Serbs lost their war with the Croats, museum attendance halved. It was one of the endless ongoing evils visited by that useless war of liberation upon a beleaguered country.

We hiked to the nearby church Mestrovic had graced with a sequence of wooden wall sculptures depicting the life of Christ. Mere yards from this holy temple, Croats swam and sunned.

High dives

Having been spoiled by my summers at Birchloft, with its sugar sand reminiscent of Lake Huron, I excused myself to read the Herald Tribune in a café. Hilly and Danny gingerly deployed themselves among the Adriatic stones. This is the most rocky country I've ever encountered— some of the stones being used by young Ivan used to teach himself to carve, including making a foot for a crippled cousin.

To return to our apartment, we strode along the rocky seacoast, teeming with locals and internationals proving to their girl friends"“ or the world in general— how brave they were to dive from perches a hundred feet or higher.

Our "apartment" (my wife ordered it on the Internet) overlooked the main train and bus station, an aberration that interrupted my wife's early morning snoozing but gave Danny and me thrilling perspectives on the tourists coming and going.

Into the sea

But the highlight of our three-day stay was a ten-hour trip into the Adriatic. The crew of the Mariner consisted of the 50ish captain and his 21-year-old son. Providentially, the captain's girlfriend's old boat had half sunk off an island, and he used the old craft as a dock to accommodate mid-sea swimmers. I still thrill at the recollection of Danny, stuffed in the circle of a lifesaver, tethered to the ladder by a strong rope, dog-paddling after his mother. The captain is an excellent cook of fresh fish served at a generous lunch.

(You may want to wear ear plugs: Captain, Jr. is obsessed with Bob Marley and Bruce Springsteen.)

But the lasting pleasure is Maria's biography. Mestrovic almost didn't survive his birth. His dirt-poor mother had to work in the fields for survival. Her women co-workers assisted the birth and then used their clothes to carry her back home.

Fighting Tito

Young Ivan received no schooling; he taught himself to read. When a Viennese industrialist gave Ivan's pastor money for the poor, the pastor urged him to support Ivan in Vienna, with the architect Otto Wagner and the painter Gustav Klimt as teachers.

There he was, speaking not a word of German. His energy and drive persuaded the authorities to be accommodating.

Mestrovic's entire life is interwoven with the Croatians' fight for freedom. He left for America to spite Tito. In 1954, Dwight Eisenhower invited him to the White House to give him an American passport.

If you're ever in South Bend, Indiana, his collection at Notre Dame is splendid— his last gesture of sharing by an admirable artist who deserves to be better known.

But what finally turned me on was the festival director's enthusiasm for a local celebrity sculptor. Ivan Mestrovic (1883-1962) had left a sizeable collection of his diverse works in stone, wood and metals to the city of Zagreb.

His home in Split is now a major museum on a hill overlooking the Adriatic, a stunning seascape I was to goggle at for hours, after as exhaustive a scrutiny as I have ever given a personal collection (while my wife guided my young son in a naked romp under the sprinkler in the garden between the museum and the sea).

From poverty to Notre Dame

In the museum store I bought Ivan Mestrovic: The Making of a Master, by the sculptor's daughter Maria, as well as a dozen postcards of his work. The book is worthy of the sculptor whom his pal Auguste Rodin ranked alongside Michelangelo. Maria is as adept at describing the harried history of Croatia as she is at describing her father's rise from deep poverty to an internationally celebrated artist in residence at Notre Dame University.

I chattered with the museum's Moldovan young lady curator-manager, who spoke fluent English. She sadly reported that after the Serbs lost their war with the Croats, museum attendance halved. It was one of the endless ongoing evils visited by that useless war of liberation upon a beleaguered country.

We hiked to the nearby church Mestrovic had graced with a sequence of wooden wall sculptures depicting the life of Christ. Mere yards from this holy temple, Croats swam and sunned.

High dives

Having been spoiled by my summers at Birchloft, with its sugar sand reminiscent of Lake Huron, I excused myself to read the Herald Tribune in a café. Hilly and Danny gingerly deployed themselves among the Adriatic stones. This is the most rocky country I've ever encountered— some of the stones being used by young Ivan used to teach himself to carve, including making a foot for a crippled cousin.

To return to our apartment, we strode along the rocky seacoast, teeming with locals and internationals proving to their girl friends"“ or the world in general— how brave they were to dive from perches a hundred feet or higher.

Our "apartment" (my wife ordered it on the Internet) overlooked the main train and bus station, an aberration that interrupted my wife's early morning snoozing but gave Danny and me thrilling perspectives on the tourists coming and going.

Into the sea

But the highlight of our three-day stay was a ten-hour trip into the Adriatic. The crew of the Mariner consisted of the 50ish captain and his 21-year-old son. Providentially, the captain's girlfriend's old boat had half sunk off an island, and he used the old craft as a dock to accommodate mid-sea swimmers. I still thrill at the recollection of Danny, stuffed in the circle of a lifesaver, tethered to the ladder by a strong rope, dog-paddling after his mother. The captain is an excellent cook of fresh fish served at a generous lunch.

(You may want to wear ear plugs: Captain, Jr. is obsessed with Bob Marley and Bruce Springsteen.)

But the lasting pleasure is Maria's biography. Mestrovic almost didn't survive his birth. His dirt-poor mother had to work in the fields for survival. Her women co-workers assisted the birth and then used their clothes to carry her back home.

Fighting Tito

Young Ivan received no schooling; he taught himself to read. When a Viennese industrialist gave Ivan's pastor money for the poor, the pastor urged him to support Ivan in Vienna, with the architect Otto Wagner and the painter Gustav Klimt as teachers.

There he was, speaking not a word of German. His energy and drive persuaded the authorities to be accommodating.

Mestrovic's entire life is interwoven with the Croatians' fight for freedom. He left for America to spite Tito. In 1954, Dwight Eisenhower invited him to the White House to give him an American passport.

If you're ever in South Bend, Indiana, his collection at Notre Dame is splendid— his last gesture of sharing by an admirable artist who deserves to be better known.

What, When, Where

Ivan Mestrovic: The Making of a Master. By Maria Mestrovic. Stacey International, 2008. 317 pages; $33.50. www.amazon.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Patrick D. Hazard

Patrick D. Hazard