Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Peter Kurt Woerner’s Odyssey is one hundred cubic inches and 3.4 pounds of gorgeous and compelling viewing/reading. Woerner and I were both in the Friends Central Class of 1960. He was personable, good looking, a stellar athlete, and dater of debutantes. To a Jewish kid from West Philly he seemed a prince of the Main Line. He’d secret-societied at Yale, then M.Arch’d it. We’d gone 50 years without contact. His book landed, unexpected as a flying saucer.

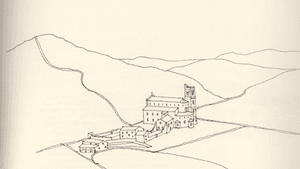

In that half-century, Woerner explored Europe, North Africa, and Central and South America, restored a Tuscan farmhouse, where he now lives several months each year, and kept sketch books throughout. On one side of Odyssey’s pages sit pen-and-inks or watercolors from these books. Opposite, a few sentences or paragraphs recount what each picture now evokes. The result blends high-end art book with graphic autobiography, each image serving him as “a visual version of Proust’s petite madeleine.”

Usually in solo-authored word-and-picture books, both elements are created closely together in time, text first and images installed as accents or compliments. But when Odyssey’s sketches were created, Woerner may never have contemplated matching words to them. When the idea occurred, he faced intriguing challenges.

Where does an odyssey begin?

Was Odyssey’s “story” known when Woerner began, determining the drawings he selected; or did this “story” evolve from viewing his drawings, and bringing continuity to them? Did he worry that the thoughts he recalled having when he sketched must have been faded by time or corrupted by subsequent experiences; or did he conclude that his present associations would suffice, as, for a psychoanalyst, a patient’s recollection of a dream is as important as what he actually dreamt? Finally, when Woerner reconstructed his experiences, what would his words include and exclude?

Odyssey is, both textually and pictorially, a compilation of sketches, or, in dictionary-speak, “short descriptions” appended to “quick, rough drawing(s) that (show) the main features of an object or scene.” Visually, “main features” work fine. A mountain range may be represented by a single wavy line, a building captured by six straight ones. Whether Woerner is rendering leather cup or Mayan ruins, urinal or piazza, his pen captures the elements sufficiently for the mind’s engagement and enrichment.

But though Woerner’s prose is equally well crafted, its restriction to “main features” becomes problematic. That I knew him makes his choices particularly provocative. From our eight years together, he mentions one teacher and a girlfriend, the rest of us pruned to fit his design. (Even his mother, who chaired Friends Central’s English department, is absent.) He ignores his athletic skill, though in those years a boy was largely defined by his athleticism. He emphasizes an enjoyment of art — Sundays at the museum, a cherished family Picasso — kept well-closeted back then.

Even readers, unacquainted with Woerner but accustomed to contemporary memoirists’ abuses, addictions, traumas, and emergence to enlightenment and best sellerdom, will be surprised. Woerner reveals his father died when he was 15 but not how this affected him. He mentions two marriages but adds nothing beyond one ex’s given name. He had relationships with a dozen women about whom he reports little besides their professions. He notes, with humor but scant detail, one bad acid trip, two knee replacements, and late-onset hand tremors. We learn that he redesigned a Manhattan hotel and converted a VFW post into apartments, and that being named a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects “meant a lot...as I often felt I was out of the mainstream, but not from where this feeling derived.

A moveable feast

Woerner seems similarly disconnected from, if not the outer world, the news media-determined representation of it. He makes virtually no reference to the shapers of popular culture of our age. However, the names he drops — Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Cy Twombly, Merce Cunningham — add a rarified coloration to his accounts.

I don’t suggest Woerner’s life remains unexamined. I believe he simply eliminated — marketplace be damned — what he felt distracted from the truths he had to tell, and these eliminations were shaped by an earlier time.

Woerner and I were among the last adolescents for whom Ernest Hemingway wrote role models. Woerner doesn’t mention Hemingway, citing only Patrick Leigh Farmer, the travel writer and war hero, as an inspiration. But Woerner’s prose — “The people, the land, the hunting. We knew it was good there” — suggests Papa’s influence. Our generation learned discretion. We kept hurts and fears private. Deeds defined us.

Deeds fill Woerner’s pages: Trout fishing, pheasant hunting, 10-day camping trips and five-day hikes, tangoing in Buenos Aires, sleeping in Romanian dives, sipping tea with Bedouins, nibbling prosciutto with a Tunisian hearse driver, eating grilled fish on the Istabul docks and vegetable gruel with monks in a Greek monastery. Woerner skies, motorcycles, sails 46-footers. “Speed and heights” are passions.

But depth and calm balance him. Cloisters, shrines, and mosques draw Woerner, the more out of the way, the stronger their pull. Museums become “houses of worship...(and) contemplation,” and his drawings “about looking and seeing and absorbing.”

Woerner concludes that life is both “journey and... adventure.” Dare much, he seems to say, and, quoting Somerset Maugham, “regret nothing.” It is a fortunate person our age who can manage that, but Woerner has set down his Odyssey free of any Cyclops or cancer, Charybdes or cardiac arrest. Losses occur — his father, the owner of a favorite ranch — but pain seems not to endure past page’s turn. Woerner appears to exist reflective, smiling in the space between each sentence.

For someone prone to gnawing past events like mutts a bone, the possibility lifts like oxygen spiking the brain.

What, When, Where

Odyssey. By Peter Kurt Woerner. Published by 9 Square Editions, 2015. $45 hardback to Peter Kurt Woerner, 44 Kendall, New Haven, CT 06512.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Bob Levin

Bob Levin