Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Pennsylvania Ballet's "Modern Masters'

'Modern,' yes. But worlds apart

LEWIS WHITTINGTON

Pennsylvania Ballet’s yearly modern program is always a harder sell than its story ballets, and this year there seemed to be more empty seats than usual. The explanation could have been Tharpian, as in Twyla. People are irrationally afraid of her. But ballet fans who held out for the spectacle of classicism missed a chance to see thrilling dance from three contemporary choreographers who, although lumped under the meaningless “modern” tag, are aesthetic worlds apart: Itinerant choreographer Kevin O’Day, San Francisco Ballet dancer-choreographer Val Caniparoli and of course the indelible Twyla Tharp herself.

O’Day’s Quartet for IV, scored to a hoe-down string chamber work by Kevin Volans, is a quick tempo roundelay for two male-female couples. The couples tentatively dance around in doodling phrases, then melt into tight partnering and complex lifts. Laura Bowman, Heidi Cruz-Austin, Maximilien Baud and Alexander Iziliaev all distinguished themselves in the piece, especially Baud in the work’s central solo. The group rightly sacrificed precision for style in the quick-tempo finale, which was a little scrambled. But this was spirited dance that neatly prologued Caniparoli’s joyous Lambarena.

Bach, pan-African style

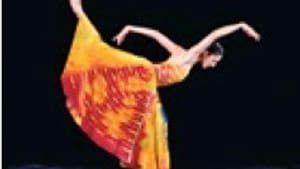

This work interlaces Bach’s music with traditional African songs (along with ambient bird caws and reed beats). The ballet challenges ballet dancers to learn pan-Africanist classicism without making it look exotic, forced or layered. Propulsive African rhythms paint the tableaux along with the brightly patterned floor length skirts swirling on the women and gazelle breeches on the men.

Caniparoli makes it a playful earth-creature-human eco-poem in dance with warrior jumps, supine bodyscapes, snaking torsos, pelvic oscillations and pulsing unison lines. Heidi Cruz is luminous as the central female dancer whose energy projects over the whole piece (Amy Aldridge was equally captivating in the alternate cast). Jermel Johnson displayed his stratospheric leaps and expressive body as the lead man. In the second cast, James Ady’s less flashy solo in front of the men’s corps was executed with his characteristic steely litheness.

Philip Colucci cockily bounded in and out of warrior poses, finishing them with saucy shoulder shakes. Francis Veyette, on the second night, gave it a more muscular reading (the shoulders coming off even more intimately). Also radiant in this choreography was principal Julie Diana, a former San Francisco Ballet dancer, demonstrating her technical prowess with huge air-slicing battlement.

Tharp’s merciless marathon

Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room is a nine-section, 40-minute marathon, in which the 13 dancers either fly through a breaking wall on endorphins or are broken in two under a merciless choreographic yoke. It puts together a dizzying display of contemporary balletic movement, displaying virtuosity in contemporary ballet movement.

At the same time, Tharp slums it with the quizzical physicality she explored in such sarcastic pieces as Push Comes to Shove. Dancers dressed in sneakers must pull off pirouettes and polished leaps, while dancers in point shoes and ballet slippers have to move under Tharp’s unrelenting tempos and unconventional patterns. Dancers appear and disappear through fog and a split back curtain, creating a netherworld scored to Philip Glass’s vertigo-inducing score. Norma Kamali’s black-and-white striped pajamas and the contrasting red Danskins are dreamy and unnerving.

Glass’s feverish dirge doesn’t let up, and when Tharp drops it into fifth gear, the Pennsylvania Ballet troupe ran through airless passages. But there were whole chunks of it not to be missed, especially in Friday’s performance during a central passage with dense choreography unspooling, so diamond-hard and surreal at once that I cried.

Outstanding were Valerie Amiss and Gabriella Yudenich as the red-pointe shoe duo in perpetual allegro motion, twirling in and out of the action. Arantxa Ochoa was nothing less than a possessed dance goddess. Veyette, Jonathan Stiles and James Ihde are the wily trio bounding in and out as if they were ready for any dance dimension and not above doing an deliberately sloppy soft shoe. Another San Francisco Ballet alum, Sergio Torrado, let his smoldering presence come through all of the choreography (as he did in his Pennsylvania Ballet Giselle debut). Sneaking in with Nike virtuosity was Martha Chamberlain, who remained the Tharpest throughout.

LEWIS WHITTINGTON

Pennsylvania Ballet’s yearly modern program is always a harder sell than its story ballets, and this year there seemed to be more empty seats than usual. The explanation could have been Tharpian, as in Twyla. People are irrationally afraid of her. But ballet fans who held out for the spectacle of classicism missed a chance to see thrilling dance from three contemporary choreographers who, although lumped under the meaningless “modern” tag, are aesthetic worlds apart: Itinerant choreographer Kevin O’Day, San Francisco Ballet dancer-choreographer Val Caniparoli and of course the indelible Twyla Tharp herself.

O’Day’s Quartet for IV, scored to a hoe-down string chamber work by Kevin Volans, is a quick tempo roundelay for two male-female couples. The couples tentatively dance around in doodling phrases, then melt into tight partnering and complex lifts. Laura Bowman, Heidi Cruz-Austin, Maximilien Baud and Alexander Iziliaev all distinguished themselves in the piece, especially Baud in the work’s central solo. The group rightly sacrificed precision for style in the quick-tempo finale, which was a little scrambled. But this was spirited dance that neatly prologued Caniparoli’s joyous Lambarena.

Bach, pan-African style

This work interlaces Bach’s music with traditional African songs (along with ambient bird caws and reed beats). The ballet challenges ballet dancers to learn pan-Africanist classicism without making it look exotic, forced or layered. Propulsive African rhythms paint the tableaux along with the brightly patterned floor length skirts swirling on the women and gazelle breeches on the men.

Caniparoli makes it a playful earth-creature-human eco-poem in dance with warrior jumps, supine bodyscapes, snaking torsos, pelvic oscillations and pulsing unison lines. Heidi Cruz is luminous as the central female dancer whose energy projects over the whole piece (Amy Aldridge was equally captivating in the alternate cast). Jermel Johnson displayed his stratospheric leaps and expressive body as the lead man. In the second cast, James Ady’s less flashy solo in front of the men’s corps was executed with his characteristic steely litheness.

Philip Colucci cockily bounded in and out of warrior poses, finishing them with saucy shoulder shakes. Francis Veyette, on the second night, gave it a more muscular reading (the shoulders coming off even more intimately). Also radiant in this choreography was principal Julie Diana, a former San Francisco Ballet dancer, demonstrating her technical prowess with huge air-slicing battlement.

Tharp’s merciless marathon

Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room is a nine-section, 40-minute marathon, in which the 13 dancers either fly through a breaking wall on endorphins or are broken in two under a merciless choreographic yoke. It puts together a dizzying display of contemporary balletic movement, displaying virtuosity in contemporary ballet movement.

At the same time, Tharp slums it with the quizzical physicality she explored in such sarcastic pieces as Push Comes to Shove. Dancers dressed in sneakers must pull off pirouettes and polished leaps, while dancers in point shoes and ballet slippers have to move under Tharp’s unrelenting tempos and unconventional patterns. Dancers appear and disappear through fog and a split back curtain, creating a netherworld scored to Philip Glass’s vertigo-inducing score. Norma Kamali’s black-and-white striped pajamas and the contrasting red Danskins are dreamy and unnerving.

Glass’s feverish dirge doesn’t let up, and when Tharp drops it into fifth gear, the Pennsylvania Ballet troupe ran through airless passages. But there were whole chunks of it not to be missed, especially in Friday’s performance during a central passage with dense choreography unspooling, so diamond-hard and surreal at once that I cried.

Outstanding were Valerie Amiss and Gabriella Yudenich as the red-pointe shoe duo in perpetual allegro motion, twirling in and out of the action. Arantxa Ochoa was nothing less than a possessed dance goddess. Veyette, Jonathan Stiles and James Ihde are the wily trio bounding in and out as if they were ready for any dance dimension and not above doing an deliberately sloppy soft shoe. Another San Francisco Ballet alum, Sergio Torrado, let his smoldering presence come through all of the choreography (as he did in his Pennsylvania Ballet Giselle debut). Sneaking in with Nike virtuosity was Martha Chamberlain, who remained the Tharpest throughout.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.