Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

"Passports to Paris' at Harrisburg

The heroism (and misery) of modern life, on French canvases

ROBERT ZALLER

A small jewel of a show is “Passports to Paris: Nineteenth-Century French Prints from the Georgia Museum of Art,” now at the Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg. It is, in its restricted compass, a tour d’horizon of 19th-Century French art in (mostly) black and white, featuring graphic work by some of that century’s most celebrated figures, including Géricault, Delacroix, Daumier, Daubigny, Manet, Whistler, Cézanne, Redon, Rodin, Renoir, Morisot, Cassatt, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as others less well known but often no less striking.

It was Baudelaire who asked the artists of his time to render what he called “the heroism of modern life”— the heroism (and misery) of labor, the energy and sprawl of great cities, the outthrust of empire, the contradictions of class culture. By and large, they responded, though in art’s oblique fashion. The Barbizon school stripped landscape of its classical associations, reveling instead in its rugged, textured density. City life received the same frank treatment, tellingly represented here in such works as Maxime Lalanne’s Rue des Marmousets, with its peeling tenement walls, and Charles Emile Jacques’ Chopping Wood in the Yard, an evocation of almost desperate poverty.

A laboring class worked to death

Felix Buhot’s L’Hiver a Paris, which not only employs virtually every print technique known to the century but glances at the emerging technology of the picture postcard, offers a snow-swept street scene with foregrounded workers, flanked by side panels that show fallen drayhorses, trudging feet, etc. Buhot makes his point by these juxtaposed but isolated images: The half-revealed underside of the bourgeois city is a laboring class worked to death.

The French empire, having been thwarted in Europe with Napoleon’s defeat, gradually occupied North Africa after 1830. Géricault’s The French Marshal, which depicts no military figure but rather a pair of sturdy horses being shod, suggests the redirecting of France’s imperial ambitions, and, with Delacroix, the long encounter of French art with the culture of the Maghreb was fully underway.

‘Unfettered sexuality’ in North Africa

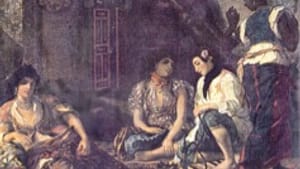

Unlike the socially conscious renderings of the changing French city and countryside, representations of Arab and Berber culture were exotic: cloistered women (Delacroix’s The Women of Algiers), cornered stallions (Felix Bracquemond’s Tethered Arab Horse, after the Delacroix original), and the like. These Orientalizing scenes naively reflected the colonial construction of North Africa as a site of unfettered sexuality awaiting the conqueror’s civilizing hand. A century later, the last of the colons, Albert Camus, would still be regretting the loss of France’s bastion of virility.

The Baudelairean artist’s last subject would be himself. Honoré Daumier gives us a rather frantic three-way portrait of the artist painting himself out of a mirror, splintered in replication. Cézanne’s depiction of his Bohemian colleague Armand Guillaumin suggests a bit of the flaneur, but also a bit of the young, truculent Picasso, whom he startlingly resembles. Manet’s The Actor of Tragedy has a tense, embattled stance: Whether at ease or attention, the 19th-Century artist understood himself as not merely an observer but a combatant. Baudelaire’s catchphrase was a call to arms.

ROBERT ZALLER

A small jewel of a show is “Passports to Paris: Nineteenth-Century French Prints from the Georgia Museum of Art,” now at the Susquehanna Art Museum in Harrisburg. It is, in its restricted compass, a tour d’horizon of 19th-Century French art in (mostly) black and white, featuring graphic work by some of that century’s most celebrated figures, including Géricault, Delacroix, Daumier, Daubigny, Manet, Whistler, Cézanne, Redon, Rodin, Renoir, Morisot, Cassatt, Gauguin and Toulouse-Lautrec, as well as others less well known but often no less striking.

It was Baudelaire who asked the artists of his time to render what he called “the heroism of modern life”— the heroism (and misery) of labor, the energy and sprawl of great cities, the outthrust of empire, the contradictions of class culture. By and large, they responded, though in art’s oblique fashion. The Barbizon school stripped landscape of its classical associations, reveling instead in its rugged, textured density. City life received the same frank treatment, tellingly represented here in such works as Maxime Lalanne’s Rue des Marmousets, with its peeling tenement walls, and Charles Emile Jacques’ Chopping Wood in the Yard, an evocation of almost desperate poverty.

A laboring class worked to death

Felix Buhot’s L’Hiver a Paris, which not only employs virtually every print technique known to the century but glances at the emerging technology of the picture postcard, offers a snow-swept street scene with foregrounded workers, flanked by side panels that show fallen drayhorses, trudging feet, etc. Buhot makes his point by these juxtaposed but isolated images: The half-revealed underside of the bourgeois city is a laboring class worked to death.

The French empire, having been thwarted in Europe with Napoleon’s defeat, gradually occupied North Africa after 1830. Géricault’s The French Marshal, which depicts no military figure but rather a pair of sturdy horses being shod, suggests the redirecting of France’s imperial ambitions, and, with Delacroix, the long encounter of French art with the culture of the Maghreb was fully underway.

‘Unfettered sexuality’ in North Africa

Unlike the socially conscious renderings of the changing French city and countryside, representations of Arab and Berber culture were exotic: cloistered women (Delacroix’s The Women of Algiers), cornered stallions (Felix Bracquemond’s Tethered Arab Horse, after the Delacroix original), and the like. These Orientalizing scenes naively reflected the colonial construction of North Africa as a site of unfettered sexuality awaiting the conqueror’s civilizing hand. A century later, the last of the colons, Albert Camus, would still be regretting the loss of France’s bastion of virility.

The Baudelairean artist’s last subject would be himself. Honoré Daumier gives us a rather frantic three-way portrait of the artist painting himself out of a mirror, splintered in replication. Cézanne’s depiction of his Bohemian colleague Armand Guillaumin suggests a bit of the flaneur, but also a bit of the young, truculent Picasso, whom he startlingly resembles. Manet’s The Actor of Tragedy has a tense, embattled stance: Whether at ease or attention, the 19th-Century artist understood himself as not merely an observer but a combatant. Baudelaire’s catchphrase was a call to arms.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller