Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Warrior Writers and Veteran Visions

PAFA presents Veteran Visions

For nearly a year, Toni Topps did not speak.

Not about signing up for the Air Force on her 19th birthday — an escape hatch, she figured, from the tedium of school and the anxiety of tuition bills. Not about slogging through basic training at Lackland Air Force base in Texas, or about finding herself, post-9/11, stationed in Saudi Arabia with a gun in her hands. Not about coming home, after four years in the military, to scrape by on a clerk’s salary of $20,000 a year, live in her mother’s duplex and rely on SNAP benefits for the food she barely had an appetite to eat.

“For a whole year, I was hospitalized,” Topps says. “I was struggling with depression and post-traumatic stress. I didn’t want to talk. I didn’t want to write. I just wanted to be normal and blend in.”

Forging a new path

{photo_2}

But the director of a veterans’ center for women, aware that Topps, before her debilitating depression, had performed spoken-word poetry in the region and even recorded a CD, nudged her toward a Warrior Writers workshop. Lovella Calica, who founded Warrior Writers, read a poem that day and offered participants a prompt: chronicle your life from pre-military time to now. Any form. No judgment. No pressure.

Topps wrote about how her youngest nephew screamed and wailed when he saw her packed suitcase on the day she left for Lackland. She wrote of guarding a gate in Saudi Arabia, where she was assigned to monitor the Muslim nationals who worked on base — “just staring at them like they weren’t really human,” a wrenching job for a woman who was on the verge of converting to Islam. And she wrote about coming home after four years of service. “Life was different. I didn’t know how to fit back into the civilian world. I tried to go back to school. There were no women’s therapy groups. I mumbled. I didn’t eat or sleep. I didn’t know how to forge relationships.”

After some writing time, Calica invited participants to read their work aloud. “I thought, ‘I’m not telling my business to these strangers,’” Topps recalls. “But everyone shared. No one was judging me. I didn’t have to prove anything. Warrior Writers challenged me…to regain my voice.”

Getting the word out

That was part of Calica’s intention when, back in 2006, she read some of her own poems to a group of Iraq war veterans and asked if they ever wrote. “Their work was so good, so powerful and important, I thought I couldn’t be the only one to hear it.” With seed money from the Leeway Foundation, Calica planned a two-day writing workshop and a self-published anthology of writing by veterans. The idea caught fire; now, in addition to the Philadelphia chapter, there are Warrior Writers groups in Boston, New Jersey, New York and the San Francisco Bay Area. Warrior Writers hosts writing and art workshops, has published four anthologies and gets paid to conduct “Veterans 101” trainings, educating audiences about traumatic brain injury and PTSD on college campuses and for other organizations.

InterAct Theatre hosted a reading by Warrior Writers members and displayed their work in conjunction with the fall production of Grounded, a play about a skilled pilot assigned to fly drones as part of the “chair force” after she becomes pregnant.

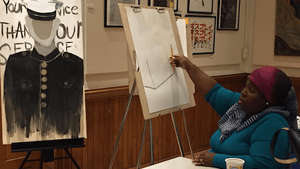

An exhibition by members of the group is on display at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through December 4, 2016. That show, an accompaniment to PAFA’s World War I and American Art exhibition, includes pieces on “combat paper” made from shredded military uniforms. Veteran Visions, which includes pen and ink drawings, acrylic paintings, and screen prints, is more stark than subtle: An acrylic-on-wood piece by former Marine machine gunner Joe Merritt depicts a soldier in a brass-buttoned blue uniform, the words “Thank you for your service” scrawled behind his head. But the soldier’s face is a mirror; get close to the artwork, and find yourself staring into your own eyes.

A screen print shows two drones dropping lidded to-go coffee cups, apt symbols of disposability and careless consumption. In Please Don’t Abandon Me, a crouching soldier covers his head as menacing arms and faces leer toward him. In Stuck, a hunched figure is nearly obscured, as if in a shrinking aperture, by a swirl of blue and white shards. A poem by Toby Hartbarger, an Army vet now studying biology, written in marker on sand-colored combat paper, reads, “When I say I am a soldier/I am not saying that I will remain stoic/I am not saying that I have no regrets…When I say I am a soldier/I am saying do not do as I did…I am saying that I’m also a human being.”

Making connections

Warrior Writers has changed since its inception, Calica says. More women and more people of color now attend the group’s workshops and events. Older veterans are involved, along with those still reeling from recent service in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“Warrior Writers has lost members to suicide,” she says. “It’s a hard struggle for a lot of people. But I’ve learned a lot about the strength and resiliency of veterans, how they can manage to keep going and adapt and figure things out.”

Topps is still writing about the experiences that haunt her. “Insomnia, I should be asleep lord,” she wrote in one poem. “Shadows grow feet and voices play hide and seek with my eyes and ears.” She’s performing her work again at open mike events. This month, she’ll accompany physician and activist Patch Adams on a Go!Clowns mission to Guatemala, an opportunity that arose after she helped facilitate a Warrior Writers workshop in Boston.

“Being connected to Warrior Writers has made me feel empowered,” she says. “I’m not afraid to put myself out there, to tell my truth, because it could save someone else.”

What, When, Where

Veteran Visions. Various artists. Through December 4, 2016 at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 118 N. Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 972-7600 or pafa.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman