Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

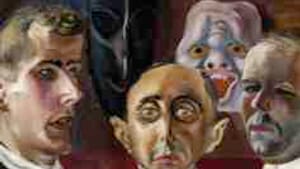

To hell and halfway back: The artist as survivor

Otto Dix at Neue Galerie in New York

World War I— the Great War, as it was known back then— coincided with the rise of the most important generation of German artists since the Renaissance. The Expressionists of Die Brucke had already made their mark before 1914, but the maelstrom of the war, in which most of them were caught up, plunged their edgy new art, with its fractured planes, raw colors and shrapnel-sharp social observation, into the fires of hell. They and their young successors left behind an unparalleled record of what are still the most traumatic four years in European history, and its embittered aftermath.

What? Worse years than World War II? For Western Europeans other from the Germans themselves, and of course Jews everywhere, yes. Hitler conquered France, the Low Countries, and Norway so swiftly in the spring of 1940 that the principal Western battlegrounds of World War I were simply zones of occupation, awaiting liberation from elsewhere. World War II offered nothing like the terrible death-embrace of trench warfare, the bloody gash that cut from the North Sea to the Swiss border and swallowed millions of lives.

No doubt war has never been more terrible than in the battle for Stalingrad in the fall and winter of 1942-43. But that was a matter of months. The trench slaughter of World War I went on for four years.

Why did German artists respond more deeply than those of any other nation to the Great War? It's a large question.

Spoiling for war?

Pre-war French Cubism was a hermetic art of pipes and guitars, a distilled Bohemianism far from social commentary. In contrast, the Berlin street scenes of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner were tense with a barely suppressed violence, while Ludwig Meidner's Apocalyptic Landscape (1913) foretold the war just around the corner.

Were the Germans ready for a war, spoiling for it? The victorious Allies at Versailles thought so, and cast the entire blame for World War I on Imperial Germany. That was at best a quarter-truth— there was bloodlust aplenty on all sides— but the Germans were more provocative, and, as newcomers to the feast of empire, more aggressive in their ambitions. They struck first, as they thought defensively, being exposed to attack on two fronts and, as a nation barely 40 years old, facing what they regarded as an existential threat.

Twenty-three-year-old Otto Dix was among the most enthusiastic volunteers for the war, and commanded a gunnery unit in the thick of the fighting. Unlike any other artist in the war, he portrayed himself as a warrior, in one sketch as a glaring, almost skull-like figure with a shaven pate, in another (How I Looked as a Soldier— the title is scrawled across the paper) cradling his machine gun in his arms, a cigarette dangling between unshaven jaws.

Witness to devastation

As the war ground on, however, its unique and unrelenting horror turned him into its most unflinching witness. Dix was to reflect on the war for decades, producing large canvases in what was then his neo-Renaissance manner well into the 1930s. But his print series, War, published in 1924, was to be his great commentary on it, one that would earn him a place beside Callot and Goya as one of the supreme chroniclers of human devastation.

All 50 of the prints Dix executed for this series are on display in the Neue Galerie's current exhibit, astonishingly the first American show ever devoted exclusively to him. They are hung in a darkened gallery— perhaps for conservatorial purposes, perhaps for dramatic ones— where one must squint to see, and progress as slowly as one would around a Stations of the Cross.

No exit

Callot and Goya placed their emphasis on civilian suffering, but the trenches of the Great War were virtually a sealed universe whose combatants faced each other at close quarters over the blasted terrain known as No Man's Land, where the only certain exit was death. The living and the dead lay promiscuously together and were in a sense indistinguishable, since the former were separated from the latter not by space but only time.

In one image, a rifleman fires over the corpse of a comrade who has become a sandbag for him, and what is shocking is not the living man's use of a dead body but the certain fact that they will soon be corpses together, one above the other. They make, that is, a kind of desperate unit, holding out until the end has come for both. Multiplied by millions, this was the Great War itself.

The most famous image of the suite— one of the definitive images of 20th-Century art— is that of a skull crawling with worms. It's not only the ultimate image of war, but one that summarizes the whole suite, with its message that, in the maw of trench warfare, the distinction between life and death is actually reversed: The living are merely the momentarily ambulant, while the dead, growing by their millions, are omnipresent.

The skull is thus both the single, anonymous victim, and the universal devourer, Death itself, whose horrible vitality flourishes down to the last morsel of human flesh.

Murdered prostitute

Dix, almost fatally wounded himself in combat, returned to the new Weimar Germany, where reminders of the war were everywhere in the maimed veterans who begged on the street. Here, too, Dix produced two of the most iconic images of the period in The Skat Players and War Cripples, both on display in the current exhibition.

The bloodlust unleashed by the war was by no means slaked, however. Dix's depiction of female nudes in the 1920s are marked by a barely contained rage, and in Raped and Murdered, the picture of a prostitute savagely slashed to death lying asprawl a hotel bed while two dogs copulate at its foot, he openly expressed the darkest fantasies.

They were not merely his own; the murdered, mutilated prostitute was a staple genre of postwar German art. But in Sex Murderer (Self-Portrait), a work later destroyed, he directly acknowledged his complicity in the violence around him. Weimar, too, was a battlefield.

Flirtation with Dada

The current exhibition is devoted to the two decades of work between 1919 and 1939. It shows the evolution of Dix's style from Expressionism through a brief flirtation with Dada to the caustic realism of the New Objectivity movement of the 1920s, and an increasing engagement with such old German masters as Altdorfer and Grunwald.

A quite similar progression can be seen in the work of his close contemporary George Grosz. Dix was much in demand as a portrait painter in the 1920s, even as he continued to paint self-portraits. Many of the commissioned portraits are well known, both from past Neue Galerie exhibitions and the Weimar survey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few years back.

A more focused show concentrated on wartime and postwar trauma, or a more comprehensive retrospective (Dix lived until 1969, and painted well into his 70s), would have been more satisfying. Neue Galerie possesses neither the deep pockets nor the gallery space for the latter, but the former would have been an achievable goal.

Still, the show is a milestone. Otto Dix is one of the most haunted, and haunting artists of the 20th Century. With our own wars at an antiseptic distance, we need someone who can bring its horrors back to us, face to face.

What? Worse years than World War II? For Western Europeans other from the Germans themselves, and of course Jews everywhere, yes. Hitler conquered France, the Low Countries, and Norway so swiftly in the spring of 1940 that the principal Western battlegrounds of World War I were simply zones of occupation, awaiting liberation from elsewhere. World War II offered nothing like the terrible death-embrace of trench warfare, the bloody gash that cut from the North Sea to the Swiss border and swallowed millions of lives.

No doubt war has never been more terrible than in the battle for Stalingrad in the fall and winter of 1942-43. But that was a matter of months. The trench slaughter of World War I went on for four years.

Why did German artists respond more deeply than those of any other nation to the Great War? It's a large question.

Spoiling for war?

Pre-war French Cubism was a hermetic art of pipes and guitars, a distilled Bohemianism far from social commentary. In contrast, the Berlin street scenes of Ernst Ludwig Kirchner were tense with a barely suppressed violence, while Ludwig Meidner's Apocalyptic Landscape (1913) foretold the war just around the corner.

Were the Germans ready for a war, spoiling for it? The victorious Allies at Versailles thought so, and cast the entire blame for World War I on Imperial Germany. That was at best a quarter-truth— there was bloodlust aplenty on all sides— but the Germans were more provocative, and, as newcomers to the feast of empire, more aggressive in their ambitions. They struck first, as they thought defensively, being exposed to attack on two fronts and, as a nation barely 40 years old, facing what they regarded as an existential threat.

Twenty-three-year-old Otto Dix was among the most enthusiastic volunteers for the war, and commanded a gunnery unit in the thick of the fighting. Unlike any other artist in the war, he portrayed himself as a warrior, in one sketch as a glaring, almost skull-like figure with a shaven pate, in another (How I Looked as a Soldier— the title is scrawled across the paper) cradling his machine gun in his arms, a cigarette dangling between unshaven jaws.

Witness to devastation

As the war ground on, however, its unique and unrelenting horror turned him into its most unflinching witness. Dix was to reflect on the war for decades, producing large canvases in what was then his neo-Renaissance manner well into the 1930s. But his print series, War, published in 1924, was to be his great commentary on it, one that would earn him a place beside Callot and Goya as one of the supreme chroniclers of human devastation.

All 50 of the prints Dix executed for this series are on display in the Neue Galerie's current exhibit, astonishingly the first American show ever devoted exclusively to him. They are hung in a darkened gallery— perhaps for conservatorial purposes, perhaps for dramatic ones— where one must squint to see, and progress as slowly as one would around a Stations of the Cross.

No exit

Callot and Goya placed their emphasis on civilian suffering, but the trenches of the Great War were virtually a sealed universe whose combatants faced each other at close quarters over the blasted terrain known as No Man's Land, where the only certain exit was death. The living and the dead lay promiscuously together and were in a sense indistinguishable, since the former were separated from the latter not by space but only time.

In one image, a rifleman fires over the corpse of a comrade who has become a sandbag for him, and what is shocking is not the living man's use of a dead body but the certain fact that they will soon be corpses together, one above the other. They make, that is, a kind of desperate unit, holding out until the end has come for both. Multiplied by millions, this was the Great War itself.

The most famous image of the suite— one of the definitive images of 20th-Century art— is that of a skull crawling with worms. It's not only the ultimate image of war, but one that summarizes the whole suite, with its message that, in the maw of trench warfare, the distinction between life and death is actually reversed: The living are merely the momentarily ambulant, while the dead, growing by their millions, are omnipresent.

The skull is thus both the single, anonymous victim, and the universal devourer, Death itself, whose horrible vitality flourishes down to the last morsel of human flesh.

Murdered prostitute

Dix, almost fatally wounded himself in combat, returned to the new Weimar Germany, where reminders of the war were everywhere in the maimed veterans who begged on the street. Here, too, Dix produced two of the most iconic images of the period in The Skat Players and War Cripples, both on display in the current exhibition.

The bloodlust unleashed by the war was by no means slaked, however. Dix's depiction of female nudes in the 1920s are marked by a barely contained rage, and in Raped and Murdered, the picture of a prostitute savagely slashed to death lying asprawl a hotel bed while two dogs copulate at its foot, he openly expressed the darkest fantasies.

They were not merely his own; the murdered, mutilated prostitute was a staple genre of postwar German art. But in Sex Murderer (Self-Portrait), a work later destroyed, he directly acknowledged his complicity in the violence around him. Weimar, too, was a battlefield.

Flirtation with Dada

The current exhibition is devoted to the two decades of work between 1919 and 1939. It shows the evolution of Dix's style from Expressionism through a brief flirtation with Dada to the caustic realism of the New Objectivity movement of the 1920s, and an increasing engagement with such old German masters as Altdorfer and Grunwald.

A quite similar progression can be seen in the work of his close contemporary George Grosz. Dix was much in demand as a portrait painter in the 1920s, even as he continued to paint self-portraits. Many of the commissioned portraits are well known, both from past Neue Galerie exhibitions and the Weimar survey at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a few years back.

A more focused show concentrated on wartime and postwar trauma, or a more comprehensive retrospective (Dix lived until 1969, and painted well into his 70s), would have been more satisfying. Neue Galerie possesses neither the deep pockets nor the gallery space for the latter, but the former would have been an achievable goal.

Still, the show is a milestone. Otto Dix is one of the most haunted, and haunting artists of the 20th Century. With our own wars at an antiseptic distance, we need someone who can bring its horrors back to us, face to face.

What, When, Where

Otto Dix. Through August 30, 2010 at Neue Galerie New York, 1048 Fifth Avenue (at 86th St.), New York. (212) 288-0665 or www.neuegalerie.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller