Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

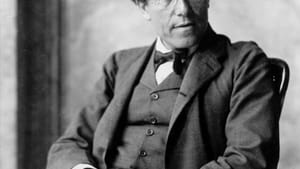

Could we all use a resurrection? Mahler thought so

Nézet-Séguin conducts Mahler (third review)

Mahler’s “Resurrection” Symphony — which set the stage for and has resonances in all his subsequent work — embodies, within the garments of Viennese angst and the story of Christ, the myth of the birth of the hero so well described by Otto Rank, Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and others.

It belongs with Beethoven’s “Eroica” Symphony and Richard Strauss’s Ein Heldenleben as among the most eloquent musical depictions of the journey to individuation and selfhood through inner struggle and confrontation with death, the warrior’s journey. At the same time, it stands with Beethoven’s Ninth “Choral” Symphony in its inclusion of a chorus in the last movement, as well as its ultimate affirmation of humanity, although it takes a very different course to get there.

Mahler was not reluctant to introduce major complexities into his work. For example, his choice of a hero is neither Napoleon nor a Germanic heroic figure. Instead, he chose a combination of a Christlike persona seeking union with God the Father through ultimate sacrifice and a Faustian figure beset by temptation and pride. Such complex understanding of the human spirit is hard enough to encompass in a musical composition, much less to realize in vivo with an expanded orchestra, offstage musicians, an odd assortment of percussion instruments, a soprano, mezzo-soprano, and augmented chorus — all while expressing the most intimate internal struggles of the human personality.

Mahler was bold enough to do both, and it could be argued that he ended up sacrificing both his marriage and his life to his audacity and desire to control large forces. Much more recently, Yannick Nézet-Séguin took on the daunting task of leading its performance and was wise enough to focus on getting the music right rather than containing all of Mahler’s psychological universe as well. As a result, he may — and may he — live a long life and add to it a long tenure with the Philadelphia Orchestra.

Another complex feature of the “Resurrection” Symphony is its form. It is a five-movement symphony of the large proportions introduced by Bruckner, whose ponderous work Brahms humorously called “boa constrictors.” But it is at the same time built around the songs and choral music at its center. The stunningly beautiful “Primal Light” soprano solo in the fourth movement, and the fifth movement incorporating a full chorus, soprano, and contralto (often a mezzo-soprano), change the entire complexion of the work and raise it to heaven. The fifth movement has the temperament of a high mass but then moves to a triumphant sense of resolution that is quite the opposite of a mass.

Mahler weaves between grief and excitement throughout the symphony. There is no conductor better than Nézet-Séguin in working with these changes, and he is excellent with liturgical and choral music as well. So the last two movements proved to be glorious in his hands, with hands and baton indicating the music in a most clear and detailed manner. The result was that the orchestra, chorus, and soloists rendered this iconic symphony with the clarity and coherence that typifies the best European ensembles.

Is Jesus the protagonist?

A key question regarding the “Resurrection” theme is whether Mahler intended the symphony to be a recapitulation of the life and death of Jesus. Mahler, a Jew who converted to Catholicism in order to overcome anti-Semitism and get the conducting job at the Vienna Hofoper, certainly had Christ in mind with respect to the idea of resurrection, and the music begins with death, considered in Christian theology the ultimate source of salvation. But the way the symphony develops doesn’t follow the story of Jesus as much as it tells of a contemporary figure who struggles within himself to find personal meaning in his life. The influence of Kierkegaard’s concepts of angst and sickness unto death is evident throughout.

The first movement begins with a funeral dirge and builds to a heroic implication with a feeling of triumph mixed with sadness and grief. There emerges a fierce, triumphant, warlike note. There then occurs a reflective, peaceful reconciliation followed by an imminent sense of fate and mortality. The protagonist is perhaps looking back on his life and asking what it all means.

The second movement affords a leisurely three-quarter time interlude that is almost too pleasant after the intensity of the first movement. This is followed by a sense of intrigue or adventure that sounds like a motif from Beethoven’s Eroica but becomes haunting melody (shades of Strauss, who composed Ein Heldenleben around the time that this symphony was first performed). This movement suggests a time of everyday living without regard to the question of eternity.

The third movement brings in the Faustian themes of temptation and the profane in the striving for greatness. Mahler, as was often his wont, introduces a “vulgar” street dance that has a Yiddish — certainly Eastern European — folk feeling. He then evokes the temptation of Viennese beauty. An orgiastic rite develops and subsides.

The brief fourth movement, “Urlicht” or “Primal Light,” begins in a solemn manner, but Mahler, characteristically, tells a childlike story of walking along a path and encountering an angel who tells him it is premature to die. The protagonist discovers, however, that he has such a profound wish to be united with God that death seems sweet.

Finally, the climactic fifth movement introduces a brooding, almost medieval, monastic darkness, followed by a contrasting martial statement of power, which then evolves into a cataclysmic struggle of forces. The atmospherics return to the quiet and darkness, and the sense of a coming presence. Finally, there is the triumphant “Resurrection.”

The symphonic development tells us that, while it embodies the Christian theme of resurrection, it is about the struggles of Mahler himself and by extension, all humankind. We live in darkness and the shadow of death, but we strive for the primal light of transcendence. By faithfully and magnificently executing the music itself, Nézet-Séguin and company avoided the extremes of morbidity and religiosity which are ever-present temptations in interpreting Mahler.

To read another review by Robert Zaller, click here.

To read another review by Steve Cohen, click here.

What, When, Where

Philadelphia Orchestra: Mahler, Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”) in C minor. Angela Meade, soprano; Sarah Connolly, mezzo-soprano; Yannick Nézet-Séguin, conductor. With Westminster Symphonic Choir; Joe Miller, director. Oct. 30-Nov. 2, 2014 at Verizon Hall, Kimmel Center, Broad and Spruce Sts., Philadelphia. 215-893-1999 or www.philorch.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Victor L. Schermer

Victor L. Schermer