Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Close encounters of the critical kind

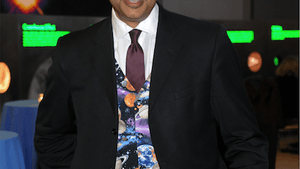

Neil deGrasse Tyson's 'An Astrophysicist Goes to the Movies'

As a filmgoer, I’m not one for verisimilitude. I watch movies with enough suspension of disbelief that as long as the proper world-building techniques are in place, I don’t care about how real a thing is. I wouldn’t know what the staterooms on the Titanic looked like, but James Cameron made them opulent enough, so I bought it. I don’t know how a planet would orbit around dual suns in Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope, but two suns in the sky looked cool, so I went for it. All I need a movie to do is serve the story.

Facts first

But then, I’m not an astrophysicist. It’s fair to say Neil deGrasse Tyson and I watch movies in entirely different ways.

Tyson, director of New York’s Hayden Planetarium, Cosmos host, and coolest guy alive, has enough to say about the way movies treat his field of expertise that he created a two-and-a-half-hour-long PowerPoint presentation and took it on a multi-city national tour. An Astrophysicist Goes to the Movies would likely have been a slog of an evening with any other host, but Tyson’s effervescent geekiness won over everyone in the audience. He called his performance “highly indulgent,” and said it would be as though “you were sitting next to me in the movie theater.”

Sitting next to Neil deGrasse Tyson in the movie theater would make for a tedious viewing experience. He quoted Mark Twain in describing how he watches movies: “Get your facts first, then distort them as you please.” He’s not necessarily looking for a coherent story, but he pays close attention to the scientific details of a film, no matter how insignificant they may seem, in hopes that a filmmaker will at least try to get them right. If the science is wrong, Tyson will make sure you know. “Am I being nit picky?” he asked. “Well, let me tell you why I’m not.”

Getting it wrong

We’d both agree on the egregious Armageddon, though not for the same reasons. Tyson played a clip from the film where Billy Bob Thorton explains that an asteroid heading towards Earth is the size of Texas, and the government has kept it secret from the public. Implausible, said Tyson: “The government can’t keep the sky a secret!” Furthermore, if an asteroid of that magnitude were coming our way, “it would’ve been discovered 200 years ago.”

Tyson has gripes about Close Encounters of the Third Kind: there is no way aliens could transmit coordinates to humans because longitude and latitude are human inventions. He also noted that the spherical BB-8 in Star Wars: The Force Awakens would “skid uncontrollably” on the sandy terrain of planet Jakku, and that Sandra Bullock’s bangs would stick straight up in Gravity, instead of falling on her forehead as though she weren’t in space.

But Tyson’s most memorable movie grievance was from Titanic, specifically the night sky shown while Rose waits to be rescued. Tyson knew exactly what the sky would look like on April 15, 1912, at the precise coordinates where the ship sank, but that was not the sky onscreen. So incensed was Tyson that he studied the sky from the film and realized it was a mirror image; the stars on the left were just a reflection of the stars on the right. He spent 15 years bugging James Cameron, until the director’s edition of the film was released in 2012 and Cameron reached out to Tyson, saying, “I hear you have a sky for me.”

Getting it right

Though Tyson has a reputation for taking the fun out of movies, his enthusiasm for the ones that get science right eclipses even his worst complaints. He undulated his whole body when explaining how surface tension works, and was thrilled to describe how both Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country and A Bug’s Life portray it accurately. He praised the consistency of the time travel in Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure, and was positively giddy about Elsa singing about “frozen fractals” in Frozen.

I thought The Martian was a laborious drag that told the same kind of story that Apollo 13 told better almost 20 years prior, but Tyson has a particular fondness for it. He didn’t go into detail about how Matt Damon’s character’s ecological system, or how astronauts, would fare in space for that long. The Martian speaks to Tyson in a more eloquent way. He explained that since the plot centers around a scientist working to live on an inhospitable planet and eventually trying to get himself off of that planet, “all your emotions are wrapped up in science and math.” The Martian is perhaps the only film that uses Tyson’s field, usually reserved for exposition and plot development, to elicit empathy from the audience.

If it’s not evident from Tyson’s pop culture presence, to hear him talk about movies makes it clear he is fascinated by everything. His energy is infectious, and his point of view emphasizes the ever-important need for critical thinking. “I’m so misunderstood,” he joked when showing clippings from various news outlets that blame him for ruining movies. But he wants people to know that recognizing errors (even if it’s as insignificant as getting Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity wrong in The Expendables 2) makes room for learning, and for him, there’s no higher goal.

I still don’t think I’m wrong for watching movies the way I do. But I’d be lying if I didn’t leave An Astrophysicist Goes to the Moves saying, “I never thought about it like that.” Neil deGrasse Tyson would consider that a win.

What, When, Where

An Astrophysicist Goes to the Movies. November 30, 2016 at the Academy of Music, 240 S. Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 893-1999 or kimmelcenter.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Angela Harmon

Angela Harmon