Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Why Die Meistersinger matters

Met’s ‘Die Meistersinger' in HDTV

Dare anyone criticize Die Meistersinger? Actually, yes. In 1882, art critic John Ruskin described Wagner’s masterpiece as “clumsy, blundering, affected, sapless, soulless, beginningless, endless.” And this month, my companion — who has seen and loved three productions of Wagner’s Ring Cycle — also registered numerous complaints about his first exposure to Meistersinger. As someone who has adored Meistersinger since my very first viewing (a Met performance way back in 1956, with Otto Edelmann and Lisa Della Casa), let me rebut his criticisms.

Complaint one: The opera is needlessly long — almost five hours, plus intermissions — typified by 20 minutes at the start before any action takes place, followed by another 20 minutes of a supporting player (the apprentice David) reciting the detailed rules of Nuremberg’s Master Singers.

My response: De Meistersinger comes from an era when audience members removed themselves from the outside world when they entered the theater. There were no distractions from cell phones, nor any TV or recordings awaiting them at home. Operas and concerts provided leisurely immersion in beautiful sounds — and the longer those sounds were stretched out, the better. I concede the first act’s longueur. But on the other hand, the third act is so beautiful that I never want it to end, even after nearly two hours.

Complaint two: Although it’s billed as a comedy, Meistersinger contains hardly any laughs, except the nasty ones aimed at Beckmesser.

My reply: It’s a comedy in the sense that it is a gentle, non-tragic look at life, much like Saroyan’s Human Comedy. We laugh gently as we recognize familiar people and situations in our own lives, chuckling as if to say, “How true.” Don’t expect the guffaws you’ll hear in Falstaff.

Stick figures?

Complaint three: Meistersinger lacks an enthralling melody like those that Wagner wrote for Isolde’s Liebestod or the Magic Fire Music or “Wintersturme” in Walkure. Walther’s prize-winning song isn’t especially rapturous.

My rejoinder: The passion between Walther and Eva is indeed pallid, and much of the score is conversational because Wagner is telling a real-life story. But one week after seeing Meistersinger, some of its tunes still dance in my head and intrude on my thoughts when I least expect them.

Complaint four: Most of the members of the masters' guild are not individualized. Despite their long periods on stage, they’re stick figures.

My response: The dignified goldsmith Pogner and the baker Kothner are personalized and are given beautiful singing opportunities. And Hans Sachs — a real shoemaker, poet, and mastersinger who was an early supporter of Luther’s Reformation — is one the fullest, richest characters in all of opera: wise and noble, humane, philosophical and forward-looking. Hans is stern one moment and loving at another. The mastersingers of Nuremberg were real, too: middle-class craftsmen who dabbled in poetry and music on the side.

It’s true that the furrier Vogelgesang, the tinsmith Nachtigall, the soapmaker Ortel, the pewterer Zorn, the tailor Moser, the coppersmith Foltz, the weaver Schwarz, and the grocer Eisslinger receive plenty of stage time but no character development. Wagner included them to demonstrate the link between work and the arts. Wagner’s glorification of the relationship between ordinary citizenry and music is one of this opera’s charms.

Nazi undertones

The basic story concerns a newcomer to Nuremberg who enters a song contest whose winner gets to marry Eva, the daughter of one of the town's leading citizens. But the appeal of the opera goes much deeper.

Meistersinger brings to life the details of a specific German city at a particular time — the mid-16th century — when religious custom was more pervasive than nationalism. Hence the inclusion of a church service, the baptism of a song, and much fuss about St. John’s Day. Luther you will recall, advocated German resistance to the papacy in nationalist terms. By Wagner's time, three centuries later, the walled medieval city of Nuremberg was a relic of the past, a “dream city,” a nostalgic representation of German identity, and Wagner tied this image to the establishment of a unified German Empire that reached achievement in 1871 — three years after Die Meistersinger’s premiere.

The opera is most notable for its dramatization of the conflict between tradition and invention. Wagner portrays most of the mastersingers as if they were the critics of his own musical innovations. He argues for accepting new ideas — like Walther’s song — yet retaining respect for society’s cultural traditions.

The opera’s fascination lies in this sociopolitical messaging, notwithstanding the disturbing language that Wagner inserted in the final scene. “We are threatened," Wagner had Sachs say. "If the German people and kingdom should one day decay under a false, foreign rule...what is German and true none would know." To Wagner, the primary threat to the health of his nation was the mixing of unlike types — perhaps the French (the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 was brewing) or maybe the Jews. Hitler amplified that notion when he wrote in Mein Kampf that the mixing of races defiles the pure blood of the German Aryan and would destroy the German nation. It’s no coincidence that Hitler’s racial prohibitions of 1935 were titled “The Nuremberg Race Laws.”

(The HDTV subtitles for this performance soften the wording and give Sachs’s valedictory a more benign tone.)

Calling Lauritz Melchior

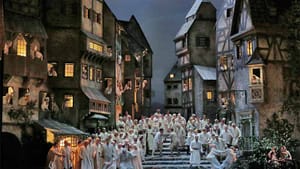

The current Met production, devised by Otto Schenk in 1993 with sets by Günther Schneider-Siemssen, will be retired at the end of this season, just as their Ring was after 2009. It’s a realistic reproduction of 16th-century Nuremberg, although the “meadow” where the song contest finale is held looks, instead, like a town square.

Michael Volle dominated the action as the wise and humane Sachs, with a warm and expressive bass-baritone. The Pogner, Hans-Peter König, displayed a mellifluous voice and warm affection for his child, Eva.

Johannes Martin Kränzle was outstanding as Beckmesser, the vindictive and authoritarian town clerk and judge of song contestants. He really sang the part instead of mugging through it.

The South African tenor Johan Botha has been praised elsewhere for his solidly sung Walther. I found his facial expressions and graceful movements — despite his very large physique — equally appealing. He’s the best tenor in this role in recent times, but his voice lacks beauty. The Wagnerian tenor Lauritz Melchior possessed a golden sound that I’ve never heard in this role, and I'm still waiting. (If any reader has an air-check of Melchior in Meistersinger, please contact me!)

Annette Dasch as Eva looked attractively homespun, but her voice was ordinary. She was at her best in her sweet opening phrases of the Act III quintet. Paul Appleby looked eager and sounded fresh-voiced as the apprentice David. (Included in Wagner’s depiction of 16th-century life was the hitting of apprentices by their mentors.)

The Met Chorus under Donald Palumbo was magnificent. James Levine’s conducted with authority; under his baton, the prelude to Act III was especially poignant.

What, When, Where

Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg. Opera by Richard Wagner; Otto Schenk directed. Metropolitan Opera production in HD at movie theaters December 13, planned for future television airing on PBS, and live through December 23, 2014 at Lincoln Center, New York. 212-362-6000 or www.metopera.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Steve Cohen

Steve Cohen