Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

When everyone draws

Knowing through drawing

Speaking in a dialect only a dental professional understands, I tell Marguerite about drawing from life — in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, at the zoo, anywhere — while she cleans my teeth.

I tell her about drawing at Julio Romero de Torres Museum, where I stopped taking seeing for granted. While looking at a still life painting, I realized that seeing the painting was not enough. I needed to draw the mysterious patterns of light and shadow to fully experience its complexities. And I talk about standing so many hours drawing one painting at the Capodimonte Museum that the guard offered me his chair.

I am passionate about drawing, and because I believe the world would be radically different if everyone drew what he or she sees, my ideas become messianic.

An essential skill

A recent Guardian article outlines the argument that drawing should be essential in all curriculums. I agree with making it a requirement but disagree that the reason it should be is its importance as a cognitive tool. Drawing intrudes beyond cognition into the realm of tacit knowledge — know-how that cannot be verbally transmitted to another, such as riding a bike — and even further, to where knowledge itself is left behind.

And even though postmodern philosophy suggests language descends into our primary perceptions — how do we perceive sky as sky without language? — visual artists know there is far less chatter down there.

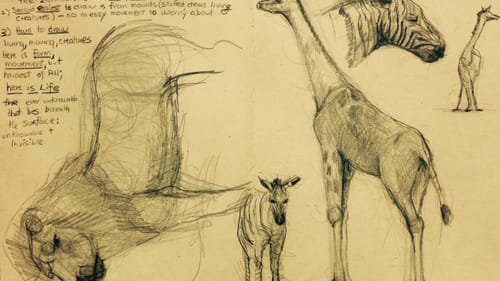

Drawing challenges me to explore different levels of awareness. Drawing from two-dimensional sources like a photograph is easy because the work is already completed; planes have been reduced, forms flattened, and light and shadow averaged. Through reduction, the world becomes itemized, providing the artist a simple shopping list to follow.

The world, immobilized

Drawing taxidermy or still life becomes more difficult because actual forms and light-shadow relationships are introduced. Yet at this level, the objects are removed from the activity of life: Animals are dead, objects have been decommissioned from use, and the world becomes immobilized, allowing the drawer to catch up.

Drawing at the Philadelphia Zoo presents yet another level of difficulty. An elephant or zebra becomes most challenging because of that enigmatic dimension of being alive, reminding me of Temple Grandin’s exclamation over a cow’s death: But where did it go? What makes a drawing of a standing cow different from a drawing of a dead and stuffed cow? In neither drawing is the cow moving or breathing. How is life acknowledged, and that knowledge transmitted, beyond biological verification?

Most often, life is defined by identifiable facts. While drawing at the zoo, I hear adults endlessly explain facts to children, making me wonder what would happen if facts weren’t force-fed? Would children explore animals in other ways? Would they discover what I have discovered — that animals become curious about me as I draw, thus equalizing the observation?

Attracting a gorilla’s attention

Initially, it was a gorilla that showed curiosity, sitting near me while I drew him for almost half an hour. When I closed my sketchbook, he walked away, leaving families with their cameras shouting for him to return. Since then, I have had similar experiences with meerkats, flamingos, and giraffes, making me think that these are not funny accidents.

I began to ask people why they don’t draw. It isn’t hard to initiate the conversation — as I am the witness to endless recitation of facts, I am also a magnet of regret.

Countless similar zoo conversations begin when the adult wants the child to demonstrate interest in my drawing. I could respond by saying that children have a natural interest in drawing until being discouraged. Instead, I ask the adult where his or her sketchbook is. Most don’t dismiss my question, instead musing that they used to draw but gave up. Sometimes drawing is dropped from lack of time, but more frequently it’s from feeling inadequate. In either case, I sense their regret.

“Perfect” portrayals

But their answers don’t really answer why, and I wonder about the relationship between an overreliance upon facts and drawing. Is good drawing equated to properly copying those facts?

Sometimes, the adult tells me the child can draw something perfectly, wanting me to conclude that the child will be an artist. But does drawing a giraffe “perfectly” suggest a potential artist or an extremely dutiful child?

Plato bemoaned mimesis because he saw our world as the mere copy of divine forms of being. How horrified he’d be at the countless drawings copied from celebrity photographs, which, if Instagram is an accurate pulse of public opinion, are now considered great art. When every rendering of, say, Brad Pitt is exactly the same regardless of the race, nationality, gender, or age of the artist, these drawings function no differently than the child repeating animal facts back to the adult.

Drawing has potential to be a singular defiant act against an accepted universal vision when drawing is seeing the ever-changing living world instead of repeating facts. Through this defiant act of drawing, I discover an invisible cord connecting me to everything, making the drawing not about things with facts but an exploration of a relationship.

Drawing becomes the contradictory activity combining defiance and connection because drawing knows no rules.

Discerning the spirit

When I return to the dentist for my six-month cleaning, Marguerite says she and her colleague Renee have been drawing at the Herbert F. Johnson Art Museum. I excitedly start talking about light, shadow, and form, but Marguerite reminds me what I know happens in drawing: She answers, When I drew, I felt the spirit of what I was seeing.

In my world, I imagine a free Draw at PMA Day where everyone is invited to draw; draw not what one is shown but what one sees in order to forge relationships where the chatter is left behind.

For an earlier essay by this author on drawing in public, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Treacy Ziegler

Treacy Ziegler