Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Juan Soriano at Art Museum (2nd review)

Death is always present (beauty, too)

ANNE R. FABBRI

Although Juan Soriano (1920–2006) belonged to the urban scene of contemporary artists and writers, he deliberately departed from their traditional social themes. His paintings extended the boundaries I had previously ascribed to Mexican art. His paintings, rendered with infinite skill and subtle palette, conduct a dialogue with European humanism, German Expressionism and the artistic turbulence of his era.

Portrait of Rebeca Uribe with the Eye of Martha (1937) recalls the 18th-Century European tradition of eye portraits on the form of ivory miniatures. Still Life with Vase and Skull (1941) is a beautifully painted, sophisticated depiction of objects recalling the vanitas paintings of the Northern Renaissance. However, in this painting the skull, covered with a sheer blue-green textile, is not so obvious. You must look carefully, then let your eyes really see the sheaf of wheat next to it, extending into the background and out to the viewer. Although death is always present, life in all its beauty continues unabated.

Child with Bird (gouache on paper, 1941) is such a striking image of a little boy dressed in a red jacket and pointed cap that you smile and shiver simultaneously. He grasps a small bird, holding it directly in front of his penis, seemingly a wry comment on the Spanish slang for male genitalia. Coupled with his lewd expression, he is not quite the epitome of childish innocence.

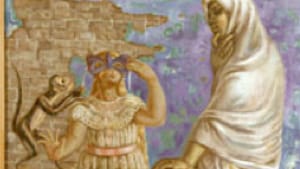

Soriano painted allegories representing his view of world affairs; his subjects stemmed from traditional folk art as well as probing portraits of friends. Saint Jerome (1942) portrays Soriano’s life-long partner, Diego de Mesa, a Spanish writer who fled to Mexico during the Civil War, as a young, male nude reclining against his desk. Behind him are books and a mirror with an image of death in the same pose, holding an hourglass: a vanitas personalized by eroticism.

Soriano and de Mesa moved to Italy in the ’50s, then to Paris. Although their living quarters remained an evocation of Mexico, Soriano became an abstract artist, then a sculptor whose monumental works now reside in France and Mexico.

The catalogue accompanying the exhibition with an essay by the guest curator, Edward J. Sullivan, is (I hope) just a preview of what could be a full retrospective of Soriano’s many facets.

To read another review by Andrew Mangravite, click here.

ANNE R. FABBRI

Although Juan Soriano (1920–2006) belonged to the urban scene of contemporary artists and writers, he deliberately departed from their traditional social themes. His paintings extended the boundaries I had previously ascribed to Mexican art. His paintings, rendered with infinite skill and subtle palette, conduct a dialogue with European humanism, German Expressionism and the artistic turbulence of his era.

Portrait of Rebeca Uribe with the Eye of Martha (1937) recalls the 18th-Century European tradition of eye portraits on the form of ivory miniatures. Still Life with Vase and Skull (1941) is a beautifully painted, sophisticated depiction of objects recalling the vanitas paintings of the Northern Renaissance. However, in this painting the skull, covered with a sheer blue-green textile, is not so obvious. You must look carefully, then let your eyes really see the sheaf of wheat next to it, extending into the background and out to the viewer. Although death is always present, life in all its beauty continues unabated.

Child with Bird (gouache on paper, 1941) is such a striking image of a little boy dressed in a red jacket and pointed cap that you smile and shiver simultaneously. He grasps a small bird, holding it directly in front of his penis, seemingly a wry comment on the Spanish slang for male genitalia. Coupled with his lewd expression, he is not quite the epitome of childish innocence.

Soriano painted allegories representing his view of world affairs; his subjects stemmed from traditional folk art as well as probing portraits of friends. Saint Jerome (1942) portrays Soriano’s life-long partner, Diego de Mesa, a Spanish writer who fled to Mexico during the Civil War, as a young, male nude reclining against his desk. Behind him are books and a mirror with an image of death in the same pose, holding an hourglass: a vanitas personalized by eroticism.

Soriano and de Mesa moved to Italy in the ’50s, then to Paris. Although their living quarters remained an evocation of Mexico, Soriano became an abstract artist, then a sculptor whose monumental works now reside in France and Mexico.

The catalogue accompanying the exhibition with an essay by the guest curator, Edward J. Sullivan, is (I hope) just a preview of what could be a full retrospective of Soriano’s many facets.

To read another review by Andrew Mangravite, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.