Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

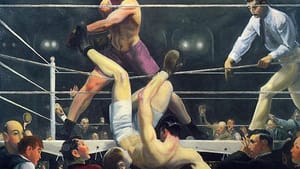

Trading in dry erase markers for arm bars

Jonathan Gottschall’s 'Professor in the Cage'

Let’s work up a strange story. Begin with a man of letters both dissatisfied with his job and nearing the age of 40. Give him a PhD, authorship of a couple semi-unknown books, and a poorly paid position as an adjunct professor at a small liberal arts college. He teaches composition to freshmen who “couldn’t care less.” Also, at times he is, perhaps, only dimly conscious of self-destructive urges — at a bare minimum, needing to be fired from the job he is trapped in.

What will he do?

The renovation of an auto-body shop for a new business, literally across the street from his office, provides the answer. Of course! He will take up mixed martial arts. He will immerse himself in a sport that’s probably second to only bull-riding in danger. No beer-league softball for this guy — he’ll face off against young men in a chain-link cage and try to beat or choke them senseless, or at least try to keep them from doing that to him.

Improbable, right? Nonetheless, this actually is Jonathan Gottschall’s story and the genesis of his new book, The Professor in the Cage.

Weaving back and forth in time and among subjects ranging from dueling and early football to left-handedness and ferret-legging (don’t ask), Gottschall admits his book isn’t quite what he thought it would be (“part history of violence, part nonfiction Fight Club, and part tour of the sciences of sport and bloodlust”). Moreover, by the time he’s finished, his assumptions about violent manliness have been turned upside down.

Content warning for readers of romance novels

So, you’re saying at this point, what do we have here? Two-hundred-some pages of blood porn or blood porn buried under an academic’s load of obtuse language? The answer is neither: Gottschall’s style is as approachable as it is frank about brutality. “Frank” doesn’t mean overdone, though. He describes quickly, for example, the very first Ultimate Fighting Championship in 1993, a contest between an enormous sumo wrestler and a karate expert half his size. The winner is determined in 20 seconds after the karate specialist strikes two blows: one punch and one soccer kick to his fallen opponent’s mouth, which leaves a tooth in the smaller man’s foot. O.K., there’s one quite nasty sentence in Gottschall’s account that doesn’t have to do with that tooth, but surely readers here are interested in the larger picture Gottschall paints.

To get to that larger picture, the writer ends up putting in 20 years of informal research on two questions: Why do men fight? And why are seemingly decent people drawn to watch?

Initially repulsed by the video of the fight described above, Gottschall wrestles for years, physically and mentally, with why “there’s nothing harder not to watch than two men fighting.”

Have the women left yet?

It is true that, for the most part, women are little discussed in this context of “real” fights, contests involving significant chances of serious injury or death, but they are there, too, and sometimes Gottschall is at least partly wrong about them, as in his reference to the “rare occasions” of women fighting physically. Mostly, however, the book is about men, the notions men have attached to dangerous contests, and the changing worlds of those contests — changes that don’t, however, obscure the relationship between aristocratic dueling and modern prison fights, for example. Of course, many women (and some men) might well say that the historical notion of “dishonor” and its modern equivalent, “disrespect,” should simply be jettisoned.

Declaring that won’t make it so, any more than declaring that gender differences are entirely cultural make them so, a point also touched on by the writer and put into the context of male posturing and fighting.

You might decide, based on this description, that this book is a rationalization for stupid male behavior, but it is in no way a stupid book. One minor flaw in Gottschall’s synthesis of exhaustive academic research and his personal experience, however, is a loose structure, prompting me to ask, more than once, “What’s this chapter about, again?”

But in any event, because you really can’t look away, you do want to know whether or not the English teacher got his clock cleaned.

What, When, Where

The Professor in the Cage: Why Men Fight and Why We Like to Watch. Jonathan Gottschall, Penguin Press, 2015. Available from Amazon.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Rick Soisson

Rick Soisson