Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Goodbye, ‘Masterpiece Theatre': Genteel Britain confronts its dark side

Jez Butterworth's "Jerusalem' on Broadway

I'm a confirmed Anglophile. I've lived in Britain, worked there, even gave birth to a son there. I travel there whenever I can to see anything that walks and talks British on the stage. The Royal National Theatre is my place of worship, along with the Donmar Warehouse, the Almeida, and many other theaters.

What appeals to me about the British, I suppose, is their strong sense of tradition and order, civility and grace— elements that are sometimes absent in our own culture. My idea of British royalty is Helen Mirren (in The Queen) and Colin Firth (in The King's Speech). I go to bed at night watching re-runs of "MasterpieceTheatre" (Foyle's War is one of my favorites). I'm addicted to "Inspector Morse" and "Inspector Lewis," and I've watched all 17 seasons of "Midsomer Murders."

The DVD release of "Downtown Abbey" (the new BBC series), about Victorian England on the brink of World War I, was a cause for celebration in my household. If some people like their tea with three lumps of sugar (like Gwendolyn in Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest), I like my Britain with three packets of Sweet & Low.

Shock to my system

So imagine the shock to my system upon seeing Jerusalem, that pulsating, profane blockbuster of a new play by Jez Butterworth now completing a dazzling run on Broadway. That shock was no doubt similar to the shock experienced last weekend by Britain's prime minister, David Cameron, who was forced to cut short his vacation in Tuscany in the face of rioting and looting that convulsed the poorer sections on London and Birmingham.

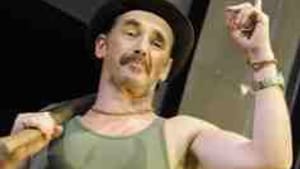

Jerusalem has won multiple awards, including a Tony for best actor in a leading role (to Mark Rylance, as the larger-than-life Johnny "Rooster" Byron). But its awards notwithstanding, Jerusalem shatters any American's fantasy of what Britain is, and I suspect any Englishman's, too.

The play tells the story of Rooster Byron, an unregistered citizen and troublemaker in "Flintock," a contemporary English village. Rooster lives illegally in a caravan on the edge of this otherwise peaceful village, happily supplying cocaine and booze to the local population, hosting all-night parties featuring sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll, fighting with his neighbors and making a general menace of himself.

After years of unsuccessful attempts to dislodge this local scourge, the authorities finally serve him notice that the land which he has unlawfully poached has been sold, and that he must vacate his caravan to make way for redevelopers who will raze it and build new housing. The locals are jubilant over Rooster's imminent departure"“ especially the father of a 15-year-old waif named Phaedre, who has run away from home and lives with Rooster in his ramshackle caravan.

Like Chekhov's old order

Jerusalem resembles Chekhov's last great play, The Cherry Orchard, wherein the old order must vacate to make way for the new. As in Chekhov's play, the members of the old order "“ meaning Rooster and his coterie of hangers-on, including a motley assortment of lost teenagers and town losers, including a professor and a pub owner"“ sit around for most of the play, talking and partying, unable and unwilling to face the inevitable.

Others come to warn Rooster that change is at hand. There's a poignant visit from Rooster's estranged wife Dawn and their six-year old son Marky, whom Rooster has promised to take to the St. George's Day village fête that very day. While Rooster explains to his son that he must break his promise (and not for the first time), Dawn surreptitiously snorts a line of cocaine that's offered openly in Rooster's front yard and warns her estranged husband that if he doesn't leave, the police will eventually arrest him, bringing more shame upon his son.

Rooster also receives an ominous visit from Troy, Phaedre's father, who threatens Rooster with violence if Rooster doesn't return Troy's daughter.

But like the characters in The Cherry Orchard, Rooster won't listen to Troy, his wife or anyone else. He clings to his old way of life, all the way up to the play's inevitable denouement.

Hymn to optimism

The key to understanding Jerusalem lies in the English hymn after which the play is named, sung several times throughout the play by the specter-like Phaedre, wearing a shimmering dress and angel wings. "And did those feet in ancient times walk upon England's mountains green?" the hymn begins, referring to a mythical visit that Jesus Christ made to England's West Country.

This popular hymn, set to William Blake's poem, is sung today in sport stadiums, churches, schools, social clubs— wherever people today gather in England to express a sense of national identity and optimism. As director Ian Rickson explains in the program notes, the hymn offers a vision of England as a place of heaven on earth, "where people live in peace and in connection with the land."

Indeed, Blake's poem was set to music in 1916 to inspire the British soldiers fighting in World War I. "I shall not cease from mental fight/Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand/Til we have built Jerusalem/In England's green and pleasant land," the hymn concludes.

Modern-day St. George

This myth of England as a "green and pleasant land" persists today, Butterworth's play is saying. Rooster Byron and all the other sociological and economical outcasts who live on society's fringe are shattering that myth.

Indeed, Rooster offers an alternative mythology for Britain. He is a modern-day St. George, a dark knight of the underbelly of British society, who will slay the dragon of Britain's entrenched institutions and steadfast traditions that exclude anyone other than the socially entitled upper classes and the parochial, white Anglo-Saxon communities like the village of Flintock.

Rooster presents himself as a mythic figure, born "on the tip of a bullet," wearing a cloak and dagger, with a full set of teeth"“ like all the Byron boys and their antecedents. He even maintains that he has met the giant who built Stonehenge. Dressed in a steel helmet in Act II, he is a warrior representing today's forces of darkness.

Primitive Celtic vision

In the play's most horrific scene, a half-naked, bloodied Rooster beats a primitive drum that lies in his front yard. As he chants the names of the Byrons before him, he invokes a grim, atavistic vision of the Celts and Normans who invaded the British Isles, whose descendants can be found today among the disenfranchised, marginalized members of British society.

The power of that final scene (and this remarkable new play) is enough to shatter any sugary myth of England's "green and pleasant land." And in light of the violence in England's cities this past week, Butterworth's prophetic play raises the timely question as to just whose "green and pleasant land" England is.

What appeals to me about the British, I suppose, is their strong sense of tradition and order, civility and grace— elements that are sometimes absent in our own culture. My idea of British royalty is Helen Mirren (in The Queen) and Colin Firth (in The King's Speech). I go to bed at night watching re-runs of "MasterpieceTheatre" (Foyle's War is one of my favorites). I'm addicted to "Inspector Morse" and "Inspector Lewis," and I've watched all 17 seasons of "Midsomer Murders."

The DVD release of "Downtown Abbey" (the new BBC series), about Victorian England on the brink of World War I, was a cause for celebration in my household. If some people like their tea with three lumps of sugar (like Gwendolyn in Oscar Wilde's The Importance of Being Earnest), I like my Britain with three packets of Sweet & Low.

Shock to my system

So imagine the shock to my system upon seeing Jerusalem, that pulsating, profane blockbuster of a new play by Jez Butterworth now completing a dazzling run on Broadway. That shock was no doubt similar to the shock experienced last weekend by Britain's prime minister, David Cameron, who was forced to cut short his vacation in Tuscany in the face of rioting and looting that convulsed the poorer sections on London and Birmingham.

Jerusalem has won multiple awards, including a Tony for best actor in a leading role (to Mark Rylance, as the larger-than-life Johnny "Rooster" Byron). But its awards notwithstanding, Jerusalem shatters any American's fantasy of what Britain is, and I suspect any Englishman's, too.

The play tells the story of Rooster Byron, an unregistered citizen and troublemaker in "Flintock," a contemporary English village. Rooster lives illegally in a caravan on the edge of this otherwise peaceful village, happily supplying cocaine and booze to the local population, hosting all-night parties featuring sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll, fighting with his neighbors and making a general menace of himself.

After years of unsuccessful attempts to dislodge this local scourge, the authorities finally serve him notice that the land which he has unlawfully poached has been sold, and that he must vacate his caravan to make way for redevelopers who will raze it and build new housing. The locals are jubilant over Rooster's imminent departure"“ especially the father of a 15-year-old waif named Phaedre, who has run away from home and lives with Rooster in his ramshackle caravan.

Like Chekhov's old order

Jerusalem resembles Chekhov's last great play, The Cherry Orchard, wherein the old order must vacate to make way for the new. As in Chekhov's play, the members of the old order "“ meaning Rooster and his coterie of hangers-on, including a motley assortment of lost teenagers and town losers, including a professor and a pub owner"“ sit around for most of the play, talking and partying, unable and unwilling to face the inevitable.

Others come to warn Rooster that change is at hand. There's a poignant visit from Rooster's estranged wife Dawn and their six-year old son Marky, whom Rooster has promised to take to the St. George's Day village fête that very day. While Rooster explains to his son that he must break his promise (and not for the first time), Dawn surreptitiously snorts a line of cocaine that's offered openly in Rooster's front yard and warns her estranged husband that if he doesn't leave, the police will eventually arrest him, bringing more shame upon his son.

Rooster also receives an ominous visit from Troy, Phaedre's father, who threatens Rooster with violence if Rooster doesn't return Troy's daughter.

But like the characters in The Cherry Orchard, Rooster won't listen to Troy, his wife or anyone else. He clings to his old way of life, all the way up to the play's inevitable denouement.

Hymn to optimism

The key to understanding Jerusalem lies in the English hymn after which the play is named, sung several times throughout the play by the specter-like Phaedre, wearing a shimmering dress and angel wings. "And did those feet in ancient times walk upon England's mountains green?" the hymn begins, referring to a mythical visit that Jesus Christ made to England's West Country.

This popular hymn, set to William Blake's poem, is sung today in sport stadiums, churches, schools, social clubs— wherever people today gather in England to express a sense of national identity and optimism. As director Ian Rickson explains in the program notes, the hymn offers a vision of England as a place of heaven on earth, "where people live in peace and in connection with the land."

Indeed, Blake's poem was set to music in 1916 to inspire the British soldiers fighting in World War I. "I shall not cease from mental fight/Nor shall my sword sleep in my hand/Til we have built Jerusalem/In England's green and pleasant land," the hymn concludes.

Modern-day St. George

This myth of England as a "green and pleasant land" persists today, Butterworth's play is saying. Rooster Byron and all the other sociological and economical outcasts who live on society's fringe are shattering that myth.

Indeed, Rooster offers an alternative mythology for Britain. He is a modern-day St. George, a dark knight of the underbelly of British society, who will slay the dragon of Britain's entrenched institutions and steadfast traditions that exclude anyone other than the socially entitled upper classes and the parochial, white Anglo-Saxon communities like the village of Flintock.

Rooster presents himself as a mythic figure, born "on the tip of a bullet," wearing a cloak and dagger, with a full set of teeth"“ like all the Byron boys and their antecedents. He even maintains that he has met the giant who built Stonehenge. Dressed in a steel helmet in Act II, he is a warrior representing today's forces of darkness.

Primitive Celtic vision

In the play's most horrific scene, a half-naked, bloodied Rooster beats a primitive drum that lies in his front yard. As he chants the names of the Byrons before him, he invokes a grim, atavistic vision of the Celts and Normans who invaded the British Isles, whose descendants can be found today among the disenfranchised, marginalized members of British society.

The power of that final scene (and this remarkable new play) is enough to shatter any sugary myth of England's "green and pleasant land." And in light of the violence in England's cities this past week, Butterworth's prophetic play raises the timely question as to just whose "green and pleasant land" England is.

What, When, Where

Jerusalem. By Jez Butterworth; directed by Ian Rickson. Through August 21, 2011 at Music Box Theatre, 239 West 45th St., New York. www.jerusalembroadway.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.