Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

From royal court to contemporary visions

Indian court drawings and modern Indian photography at the Art Museum

The artistic past and present of the second most populous nation on Earth are surveyed in two exhibits at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Drawn from Courtly India and Contemporary Photography and India bookend four centuries of Indian art.

Recently acquired works from royal courts of the 16th through 19th centuries pull aside the curtain on Northern India studios, revealing apprentice training and the detailed creation of ink sketches. From preliminary to ready-for-color drawings, 65 works illuminate how nascent artists took on increasingly advanced tasks — and document the culture around them. The Birth of Krishna (c 1780), for example, is a busy nativity scene that unfurls within the lacy architecture of a palatial home: Mother and child rest in an upper room, excited visitors enter below, and exuberant musicians serenade crowds gathering in the street.

Finding a depiction of Christ (Crucifixion, c. 1580-1620), is surprising until the context is understood: Though intrigued by Christian missionaries’ stories, the work represents not religious conversion, but artists’ embrace of new material to draw. Other works need no explanation: Men Falling from Their Rearing Horses (c 1790) conveys speed, gravity, drama, and even humor in a few well-placed lines. Riders tumble backward, a turban unravels as it rolls across the ground, and taut reins twist equine necks as their hooves fly into the air.

Ancient techniques familiar to modern eyes

When changes were needed and copies had to be made, the methods that court artists used 400 years ago would be recognizable to 21st-century office dwellers. With a swipe of white pigment, a figure’s position could be altered or a disgraced courtier deleted. (white-out and Photoshop, anyone?) Once the figures were placed, finish detail was added in filament-fine lines, and barely visible shading provided subtle dimension. Color came last, one shade at a time.

Hand-held magnifiers are available to appreciate the work more easily, and videos in the gallery and on the PMA website provide time-lapse coverage of techniques, such as pouncing. This duplication technique involves perforating the lines of the drawing to be copied with a stylus, then daubing the drawing with a pouch of charcoal dust. This produces a duplicate outline on a blank sheet beneath — just slightly more primitive than carbon paper, for those who remember that particular bit of office technology.

A concurrent Perelman exhibit, Picture This: Contemporary Photography and India, brings Indian art into the present through the eyes of four photographers.

Gauri Gill: girl power

Born in India in 1970, Gauri Gill depicts marginalized communities. Visiting a Rajasthan fair for girls in 2003 and returning in 2010, she created the Balika Mela series in which her subjects chose how to dress and pose. Gill also taught girls attending the fair how to take and develop photographs. The 2003 portraits are large black-and-white images that might be timeless save for the occasional detail, such as a camera slung around a subject’s neck, as in Madhu and Rampyari (2003). Like all of the Balika Mela subjects, Sunita, Sita, and Nirmela (2003) exude confidence: They look right at us, expressions serious, posture erect. In 2010, Gill altered her approach, shooting in color and printing in standard portrait size. The resulting photos are propped on a shelf, contemporary and ordinary. Though the girls’ attitudes are similar to their 2003 counterparts, their power is diminished by choices beyond their control, perhaps a commentary on the vulnerability of all marginalized groups to decisions made elsewhere.

Sunil Gupta: discovering home

Sunil Gupta’s words inform the experience of viewing his photographs. The Canadian-born son of Indian immigrants, he was cut off from his heritage by more than geography — as a gay man, he could not be open with his father about his sexuality. Now, though, he addresses the older man in the captions to his photos.

“You were let down,” he writes in a photo caption. “I didn’t marry and give you a grandson. . . .The disappointment stood between us. . . .We never directly addressed it. There was no vocabulary.” The words accompany an untitled photo taken in 1982, when he and his father visited their ancestral village, Mundia Pamar. It was to be the older man’s last time in India. In the picture, Gupta stands behind his seated father, who looks to the side. Gupta embraces him, resting his chin on his father’s white hair.

Gupta’s work in India, which includes Country: Portrait of an Indian Village, spans three decades and features simple village scenes, crumbling landmarks, landscapes swathed in fog, and, in images made in the early 1980s, subtle documentation of gay men, who then could not live openly in India.

Max Pinckers: social imperatives

India is just one of the places in which Max Pinckers has lived and worked. A Belgian by birth, his works from Will They Sing Like Raindrops or Leave Me Thirsty (2014) employ various approaches — journalistic, staged dramatic scenes; collaborative sculpture; and found material — to comment on modern India. Pinckers’s message is not always clear, and with scant explanation, the impact depends on the viewer’s perception.

The most striking photograph is a massive print of two jagged lines of little white cars, frozen in place on a snaking mountain road. Craggy, snow-capped peaks mirror the road, but the cause of the endless bumper-to-bumper jam isn’t visible. Drivers are out of their vehicles, milling about. The scene recalls a grid puzzle in which only one tile can move at a time, except there is nowhere for any of the cars to go. Is Pinckers commenting on overcrowding in India, home to 1.3 billion? The environmental damage done by cars? The meaning of life? Who knows?

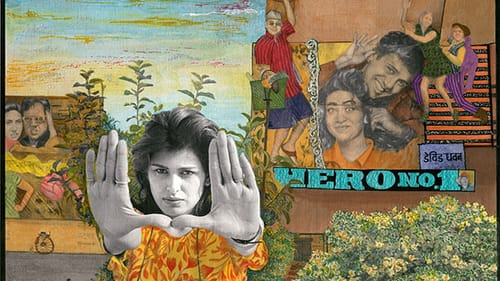

Pamela Singh: selfies done right

Pamela Singh turned her journalistic lens to art photography in the 1990s. Though the subjects didn’t change much, her visibility did, as Singh entered the frame with the help of a rear-view mirror attached to her camera, long before the emergence of selfies. She may be a wisp of windblown hair at the perimeter, a face in the crowd, or a front-and-center occupant, as in Treasure Map 006 (1994-1995 negative; 2004-2005, print) the image used as the exhibit icon.

With youthful experience in celebrity (Miss India 1982) and scandal before taking up photography, Singh was uniquely qualified to anticipate selfie culture. However, rather than pursuing relentless and indiscriminate documentation, Singh’s incursion examines the roles of observer and observed and the nature of celebrity. Her approach underscores the ways in which even the most selective and self-effacing photographer is always in her image.

What, When, Where

Drawn from Courtly India: The Conley Harris and Howard Truelove Collection, to March 27, 2016. Picture This: Contemporary Photography and India, to April 3, 2016. Philadelphia Museum of Art, Perelman Building, 2525 Pennsylvania Avenue, Philadelphia. 215-763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.