Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Know who did that? Harry

Harry Bertoia at Rosemont College

Some artists slip under the radar because their work is too little exposed. The Italian-American artist Harry Bertoia (1915-1978), best known as a sculptor and designer, created some 50 public monuments to go with the work of such renowned architects as Eero Saarinen, Edward Durrell Stone, and I. M. Pei. He also worked with the no less famous Charles Eames in the design of modern furniture, including those ubiquitous outdoor wire chairs now (in their knockoff versions) standard fare in parks, museums, and sidewalk cafes.

If you've ever visited the celebrated MIT chapel, you'll have seen the splendid wire curtain that descends from behind the altar, suggesting the fall of grace. Know who did that? Harry.

Bertoia will soon get his due, thanks to a new book devoted to him with a major essay by Donald Kuspit. Interestingly, though, Bertoia always thought of his drawings as his most privately important work, the journal of his days.

Rosemont College has mounted a small but choice show of these in the gallery of Lawrence Hall, together with several examples of his "sound" or "tonal" sculpture— upright rods or bushlike arrays that vibrate, each with its characteristic note, when touched or stroked.

When a fellow visitor touched one, the sound was so rich and impressive that I thought at first the bells of Rosemont's chapel had rung. Bertoia used these "instruments" to create musical clusters that have been recorded on CD.

Fleeing Mussolini

Bertoia was born in the Udine in 1915. He emigrated to Detroit in 1930, a good time to get out of Mussolini's Italy but not a very good one to come to Detroit. A scholarship enabled him to study art, although the nonobjective style he favored wasn't welcome locally.

In a bold, not to say presumptuous, move for an artist in his 20s, Bertoia sent a hundred of his drawings to Hilla Rebay at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. She bought them all, and exhibited 19 of them in a group show in 1943.

As Bertoia's drawings from the 1940s show, he had much in common with his contemporaries of what later became known as the New York School. But unlike them, he seems to have had little interest in easel painting, dividing his time mostly between sculpture and high-end design.

Spontaneous drawings

He never ceased to draw, however. Bertoia's technique was unusual; he inked plates, as for etchings or woodcuts, and then, using the result as a ground, drew on the reverse side. This practice did lead him into graphic work proper, as in the monotypes he executed in the '40s; some drawings, too, were sketches for sculpture.

Most frequently, however, Bertoia drew spontaneously (the drawings in the present show are all inks), letting his mood carry him. The result invariably shows a powerful sense of form and fluid control.

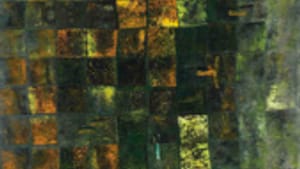

There are also a good many influences and affinities: Henry Moore and the powerful, quasi-sculptural Cubist forms of Arshile Gorky from the 1930s; Paul Klee in the large, multicolored box patterns of #255, a work from the 1940s that's one of the show's highlights; Hans Hartung in the bunched lines and strokes of some of Bertoia's late work from the 1970s.

It is these presences that, I think, keep Bertoia's graphic art from the very first rank. He's never merely imitative, but the more powerful signatures visible in his work seem never quite worked out of his style.

Considerable pleasures will nonetheless be found in these drawings, and as a body of work they have much to say about the directions of American art in the mid-20th Century. Their final limitation, however, may have been sensed by Bertoia himself.

"Communication is impossible," he said, "but nonetheless unavoidable." The impulse to speak without a voice distinct enough to forcefully impose itself is the fate of many a fine artist not good enough to be great.♦

To read responses, click here.

If you've ever visited the celebrated MIT chapel, you'll have seen the splendid wire curtain that descends from behind the altar, suggesting the fall of grace. Know who did that? Harry.

Bertoia will soon get his due, thanks to a new book devoted to him with a major essay by Donald Kuspit. Interestingly, though, Bertoia always thought of his drawings as his most privately important work, the journal of his days.

Rosemont College has mounted a small but choice show of these in the gallery of Lawrence Hall, together with several examples of his "sound" or "tonal" sculpture— upright rods or bushlike arrays that vibrate, each with its characteristic note, when touched or stroked.

When a fellow visitor touched one, the sound was so rich and impressive that I thought at first the bells of Rosemont's chapel had rung. Bertoia used these "instruments" to create musical clusters that have been recorded on CD.

Fleeing Mussolini

Bertoia was born in the Udine in 1915. He emigrated to Detroit in 1930, a good time to get out of Mussolini's Italy but not a very good one to come to Detroit. A scholarship enabled him to study art, although the nonobjective style he favored wasn't welcome locally.

In a bold, not to say presumptuous, move for an artist in his 20s, Bertoia sent a hundred of his drawings to Hilla Rebay at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. She bought them all, and exhibited 19 of them in a group show in 1943.

As Bertoia's drawings from the 1940s show, he had much in common with his contemporaries of what later became known as the New York School. But unlike them, he seems to have had little interest in easel painting, dividing his time mostly between sculpture and high-end design.

Spontaneous drawings

He never ceased to draw, however. Bertoia's technique was unusual; he inked plates, as for etchings or woodcuts, and then, using the result as a ground, drew on the reverse side. This practice did lead him into graphic work proper, as in the monotypes he executed in the '40s; some drawings, too, were sketches for sculpture.

Most frequently, however, Bertoia drew spontaneously (the drawings in the present show are all inks), letting his mood carry him. The result invariably shows a powerful sense of form and fluid control.

There are also a good many influences and affinities: Henry Moore and the powerful, quasi-sculptural Cubist forms of Arshile Gorky from the 1930s; Paul Klee in the large, multicolored box patterns of #255, a work from the 1940s that's one of the show's highlights; Hans Hartung in the bunched lines and strokes of some of Bertoia's late work from the 1970s.

It is these presences that, I think, keep Bertoia's graphic art from the very first rank. He's never merely imitative, but the more powerful signatures visible in his work seem never quite worked out of his style.

Considerable pleasures will nonetheless be found in these drawings, and as a body of work they have much to say about the directions of American art in the mid-20th Century. Their final limitation, however, may have been sensed by Bertoia himself.

"Communication is impossible," he said, "but nonetheless unavoidable." The impulse to speak without a voice distinct enough to forcefully impose itself is the fate of many a fine artist not good enough to be great.♦

To read responses, click here.

What, When, Where

“Harry Bertoia: Four Decades of Drawings.†Closed September 20, 2011 at Rosemont College, 1400 Montgomery Ave., Rosemont, Pa. (610) 526.2697 or www.rosemont.edu.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller