Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

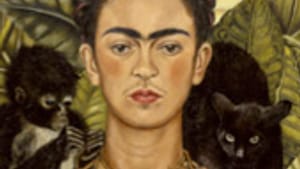

"Frida Kahlo' at Art Museum (1st review)

Neither dreamer nor victim:

The misunderstood Frida Kahlo

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

“I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

—Frida Kahlo.

Not every painter figuratively and literally gives the brush to Surrealism’s pope, Andre Breton, when he invites them into his très chic art movement. But of course Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) wasn’t every painter. She was Frida Kahlo, and the only person who could make her jump through hoops was her big baby gifted with the third eye of Wisdom, Diego Rivera.

In 1938, not long after she explained to Breton that she wasn’t a painter of dreams, Kahlo was enjoying the opening of her first solo exhibition at the Julian Levy Gallery in New York City. At the opening she met Clair Boothe Luce, wife of the Time magazine publisher, and the conversation turned to the recent suicide of their mutual friend, the showgirl-turned-socialite Dorothy Hale, whose savings had become depleted after her husband’s death. Dorothy had thrown a big party for all of her friends and, in the early hours of the next morning, leaped to her death from the window of her apartment.

Kahlo suggested that she might paint a recuerdo commemorating the event. Luce, apparently believing a recuerdo to be some sort of idealized memorial portrait, readily agreed to finance the work, thinking it might make a comforting tribute for poor Dorothy's mother. If Luce’s notion struck Kahlo as a bit odd, she apparently kept it to herself. Consequently, when Luce received and uncrated the finished work, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, now widely considered to be one of Kahlo’s masterpieces, she experienced a major case of “culture shock.”

A miraculous solution to a problem

How could anyone be so insane as to paint the bloody, broken body of their friend, lying in the street? And with added ghoulishness, Kahlo depicted secondary “stop-motion” images of Dorothy emerging from the window and tumbling in mid-air. But worst of all, she had the chutzpah to include an angel holding a banner declaring that she, Clare Boothe Luce, had commissioned this abomination!

Well, what could Luce be expected to know about Mexican colonial-era art? For that matter, how well had she really studied Kahlo’s work? Luce viewed the death of Dorothy Hale as an All-American tragedy—a high-flying lifestyle and suddenly, no more money, and no way to get more. Kahlo undoubtedly saw it a bit differently. In traditional Mexican art, recuerdos were a form of visual reportage, frequently extolling a miraculous solution to a problem: a lost child found, an illness recovered from. In a way, Dorothy Hale’s leap was a solution to her problem. Frida herself would write as the last entry in her diary, “I hope the leaving is joyful—and I hope never to return.” Perhaps she felt that Dorothy, having spent the evening with her charming friends, wearing her favorite black velvet dress—the one Dorothy herself referred to as her femme fatale dress—had chosen a joyful leaving.

Only Mrs. Luce's Yankee thrift kept her from destroying the painting— although she had the offending angel and banner removed, and had the inscription at the bottom of the painting altered as well. The painting did not go to Dorothy’s mother.

No star-struck adolescent

Perhaps as a way of preventing such cross-cultural misunderstandings, “Frida Kahlo,” the new exhibition of her work at the Art Museum, introduces us to a plethora of photographs of Frida, her family and her husband Diego Rivera before we ever get to her image-rich, highly idiosyncratic work. A family photo from 1926 shows Frida boldly wearing one of her father’s suits, and the exhibit notes mention “the artist’s expertise at seducing the camera.” In short, this section introduces us to Frida the Celebrity, a friend of Breton and Trotsky, though she was no star-struck adolescent.

This acerbic account of her participation in one of Breton’s exhibitions of surrealist art, held in Paris in 1939, should make that quite clear: “My exhibit was not ready— my paintings were quietly waiting for me at the customs office because Breton had not even picked them up. You don’t have even the slightest idea of what kind of old cockroach Breton is, along with almost all those in the surrealists’ group. In a few words, they’re a bunch of perfect sons of… their mother. I’ll tell you the whole story about the exhibition when we see each other’s faces again, since it is long and sad.” Clearly, Frida was neither dreamer nor victim.

Luther Burbank, half-vegetable

She was something of an indigenist, in that she assiduously cultivated both colonial and pre-colonial Mexican motifs in her art. This is not to say that Kahlo quoted them for bits of exotic color. No, she seems to have truly believed in them. They were not examples of an obsolete visual vocabulary; to her, they were expressions of universal truth.

In a sense Frida was an extremely classy folk artist. Her husband, Diego Rivera, may have quoted motifs as a shortcut to obtaining “historical sweep” in his epic murals, but Frida really did pray to the old gods. Because her work is so old— older than Cortez, and yet so new (Luther Burbank the horticulturalist depicted in a memorial portrait as being himself half vegetable with roots taking nourishment from his own moldering corpse)— it becomes timeless. It also suggests that Mrs. Luce probably wouldn’t have been any happier with a memorial portrait of Dorothy Hale, had Frida painted her one.

To read another review by Anne R. Fabbri, click here.

To read another review by F. Lennox Campello, click here.

The misunderstood Frida Kahlo

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

“I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality.”

—Frida Kahlo.

Not every painter figuratively and literally gives the brush to Surrealism’s pope, Andre Breton, when he invites them into his très chic art movement. But of course Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) wasn’t every painter. She was Frida Kahlo, and the only person who could make her jump through hoops was her big baby gifted with the third eye of Wisdom, Diego Rivera.

In 1938, not long after she explained to Breton that she wasn’t a painter of dreams, Kahlo was enjoying the opening of her first solo exhibition at the Julian Levy Gallery in New York City. At the opening she met Clair Boothe Luce, wife of the Time magazine publisher, and the conversation turned to the recent suicide of their mutual friend, the showgirl-turned-socialite Dorothy Hale, whose savings had become depleted after her husband’s death. Dorothy had thrown a big party for all of her friends and, in the early hours of the next morning, leaped to her death from the window of her apartment.

Kahlo suggested that she might paint a recuerdo commemorating the event. Luce, apparently believing a recuerdo to be some sort of idealized memorial portrait, readily agreed to finance the work, thinking it might make a comforting tribute for poor Dorothy's mother. If Luce’s notion struck Kahlo as a bit odd, she apparently kept it to herself. Consequently, when Luce received and uncrated the finished work, The Suicide of Dorothy Hale, now widely considered to be one of Kahlo’s masterpieces, she experienced a major case of “culture shock.”

A miraculous solution to a problem

How could anyone be so insane as to paint the bloody, broken body of their friend, lying in the street? And with added ghoulishness, Kahlo depicted secondary “stop-motion” images of Dorothy emerging from the window and tumbling in mid-air. But worst of all, she had the chutzpah to include an angel holding a banner declaring that she, Clare Boothe Luce, had commissioned this abomination!

Well, what could Luce be expected to know about Mexican colonial-era art? For that matter, how well had she really studied Kahlo’s work? Luce viewed the death of Dorothy Hale as an All-American tragedy—a high-flying lifestyle and suddenly, no more money, and no way to get more. Kahlo undoubtedly saw it a bit differently. In traditional Mexican art, recuerdos were a form of visual reportage, frequently extolling a miraculous solution to a problem: a lost child found, an illness recovered from. In a way, Dorothy Hale’s leap was a solution to her problem. Frida herself would write as the last entry in her diary, “I hope the leaving is joyful—and I hope never to return.” Perhaps she felt that Dorothy, having spent the evening with her charming friends, wearing her favorite black velvet dress—the one Dorothy herself referred to as her femme fatale dress—had chosen a joyful leaving.

Only Mrs. Luce's Yankee thrift kept her from destroying the painting— although she had the offending angel and banner removed, and had the inscription at the bottom of the painting altered as well. The painting did not go to Dorothy’s mother.

No star-struck adolescent

Perhaps as a way of preventing such cross-cultural misunderstandings, “Frida Kahlo,” the new exhibition of her work at the Art Museum, introduces us to a plethora of photographs of Frida, her family and her husband Diego Rivera before we ever get to her image-rich, highly idiosyncratic work. A family photo from 1926 shows Frida boldly wearing one of her father’s suits, and the exhibit notes mention “the artist’s expertise at seducing the camera.” In short, this section introduces us to Frida the Celebrity, a friend of Breton and Trotsky, though she was no star-struck adolescent.

This acerbic account of her participation in one of Breton’s exhibitions of surrealist art, held in Paris in 1939, should make that quite clear: “My exhibit was not ready— my paintings were quietly waiting for me at the customs office because Breton had not even picked them up. You don’t have even the slightest idea of what kind of old cockroach Breton is, along with almost all those in the surrealists’ group. In a few words, they’re a bunch of perfect sons of… their mother. I’ll tell you the whole story about the exhibition when we see each other’s faces again, since it is long and sad.” Clearly, Frida was neither dreamer nor victim.

Luther Burbank, half-vegetable

She was something of an indigenist, in that she assiduously cultivated both colonial and pre-colonial Mexican motifs in her art. This is not to say that Kahlo quoted them for bits of exotic color. No, she seems to have truly believed in them. They were not examples of an obsolete visual vocabulary; to her, they were expressions of universal truth.

In a sense Frida was an extremely classy folk artist. Her husband, Diego Rivera, may have quoted motifs as a shortcut to obtaining “historical sweep” in his epic murals, but Frida really did pray to the old gods. Because her work is so old— older than Cortez, and yet so new (Luther Burbank the horticulturalist depicted in a memorial portrait as being himself half vegetable with roots taking nourishment from his own moldering corpse)— it becomes timeless. It also suggests that Mrs. Luce probably wouldn’t have been any happier with a memorial portrait of Dorothy Hale, had Frida painted her one.

To read another review by Anne R. Fabbri, click here.

To read another review by F. Lennox Campello, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.