Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

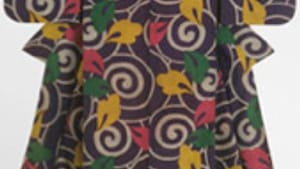

"Fashioning Kimono' at Art Museum

A bit of your soul, and a small miracle of design

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

Japan’s big impact on late 19th-Century European art is an old story. Perhaps less well known is the story of the reciprocal impact that Western culture exerted on late 19th and early 20th Century Japanese art and literature.

The fact that Western (in fact, American) writers like Lafcadio Hearn and Ernest Fenollosa traveled to Japan and virtually transformed themselves into Japanese might leave us with the impression that the cultural exchange was strictly a one-way street— that Westerners plundered the treasures of the Orient, giving in return only glass beads and worthless trinkets. Certainly the Japanese of the period made some odd choices, elevating authors who at the time were considered somewhat-less-than-stellar by their home audiences (i.e.: Baudelaire, Strindberg) into major figures in the Western cultural pantheon. And I’m certain that Japanese scholars would tell us in return that some Japanese art works that sent the likes of Van Gogh and the Goncourts into paroxysms of aesthetic ecstasy were decidedly second-rate pieces. (That’s why they were exported to Europe in the first place.)

Kimono are a treasured part of Japanese culture. In the early 20th Century, they were still the garment of choice for most Japanese men and women. Women especially treasured their kimono as an almost spiritual object— a bit of their souls on display. How could the alien culture of the West impact upon so intimate a piece of Japanese culture? Quite benignly on the whole, as the new exhibition “Fashioning Kimono” at the Art Museum attests.

The tragedy of all boys

As one might expect, the women’s kimono received the most artistic treatments, while the more embarrassing translations seemed reserved for Japanese boys. (This is the tragedy of all boys, who want so desperately to be treated as little adults but more often wind up as family pets. Would a 1920s Japanese boy in his kimono emblazoned with battleships and bi-planes feel any differently than an American boy of the 1950s with Davy Crockett emblazoned on his “jammies”?)

Japanese men wore kimono that were severe on the outside but had traditional scenes painted on their inner linings, while their somewhat gaudier under kimono might be decorated with anything from Christian icons to racehorses (the garb of choice for flush racetrack touts, no doubt).

Much of the Art Museum’s show is given over to women’s kimono, under kimono and kimono jackets, which is all to the good, since they constitute a virtual seminar in design trends. A successful piece of design is always a small miracle, blending beauty and practicality in such a way that it looks inevitable, as if it existed from the dawn of time. But of course it didn’t. A designer had to conceive of it.

A Rembrandt vs. a sports car

Design speaks to us in a different way than fine art. You appreciate the heft of a fine kitchen knife, or the lines of a sports car because the object becomes an extension of you. A Rembrandt, no matter how much you may love or admire it, is never yours. It’s Rembrandt’s. It’s Rembrandt speaking to you over a gulf of time and space. But the men and women who wore these kimono turned themselves into walking works of art.

The exhibition’s earlier works still cling to Japanese design traditions but sneak in an occasional hint of modernity. It’s ironic that Art Nouveau, which profited so mightily from exposure to Japanese export art, was able to effect so little change in the Japanese aesthetic in return. You might see a stylized circular “Mackintosh rose” introduced into a certain design, but for the most part, women’s kimono of the period seemed more resistant to the wholesale appropriation of Western motifs than those worn by their men.

But by the 1920s, with Art Deco roaring in, everything changes and women’s kimono become riots of abstract design and screaming colors. One can only imagine the effect a group of women strolling down the avenue would have made on passers-by. It was probably similar to the impact of mauve on mid-Victorian eyes. Certainly these bold new styles suggested a new type of Japanese woman who had read her Akiko Yosano, made notes in the margins, and was now looking for more of the freedoms enjoyed by her Western sisters.

What militarists prefer on their sleeves

Sadly, the flowering of modernism in post-World War I Japan was as short-lived as the flowering of modernism in post-revolutionary Russia. Militarists and authoritarians of all stripes always seem more comfortable wearing airplanes and battleships on their sleeves than Mackintosh roses. Japan’s increased militancy during the 1930s led to a resolute rejection of all things non-traditional (and thus non-Japanese). Japan’s increasingly desperate situation as World War II wore on resulted in the loss of many kimono, both from bombing raids and relentless austerity drives. (Kimono were literally re-cut into work cloths.)

After the war, Western clothing became the preferred style, and now Kimono are treasured as ceremonial garments and as a part of a national cultural patrimony. This is a wonderful chance for Philadelphians to see these fragile examples of portable beauty. The show’s catalogue is also a knockout and will tell you everything you ever wanted to know about the design and manufacture of kimono.

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

Japan’s big impact on late 19th-Century European art is an old story. Perhaps less well known is the story of the reciprocal impact that Western culture exerted on late 19th and early 20th Century Japanese art and literature.

The fact that Western (in fact, American) writers like Lafcadio Hearn and Ernest Fenollosa traveled to Japan and virtually transformed themselves into Japanese might leave us with the impression that the cultural exchange was strictly a one-way street— that Westerners plundered the treasures of the Orient, giving in return only glass beads and worthless trinkets. Certainly the Japanese of the period made some odd choices, elevating authors who at the time were considered somewhat-less-than-stellar by their home audiences (i.e.: Baudelaire, Strindberg) into major figures in the Western cultural pantheon. And I’m certain that Japanese scholars would tell us in return that some Japanese art works that sent the likes of Van Gogh and the Goncourts into paroxysms of aesthetic ecstasy were decidedly second-rate pieces. (That’s why they were exported to Europe in the first place.)

Kimono are a treasured part of Japanese culture. In the early 20th Century, they were still the garment of choice for most Japanese men and women. Women especially treasured their kimono as an almost spiritual object— a bit of their souls on display. How could the alien culture of the West impact upon so intimate a piece of Japanese culture? Quite benignly on the whole, as the new exhibition “Fashioning Kimono” at the Art Museum attests.

The tragedy of all boys

As one might expect, the women’s kimono received the most artistic treatments, while the more embarrassing translations seemed reserved for Japanese boys. (This is the tragedy of all boys, who want so desperately to be treated as little adults but more often wind up as family pets. Would a 1920s Japanese boy in his kimono emblazoned with battleships and bi-planes feel any differently than an American boy of the 1950s with Davy Crockett emblazoned on his “jammies”?)

Japanese men wore kimono that were severe on the outside but had traditional scenes painted on their inner linings, while their somewhat gaudier under kimono might be decorated with anything from Christian icons to racehorses (the garb of choice for flush racetrack touts, no doubt).

Much of the Art Museum’s show is given over to women’s kimono, under kimono and kimono jackets, which is all to the good, since they constitute a virtual seminar in design trends. A successful piece of design is always a small miracle, blending beauty and practicality in such a way that it looks inevitable, as if it existed from the dawn of time. But of course it didn’t. A designer had to conceive of it.

A Rembrandt vs. a sports car

Design speaks to us in a different way than fine art. You appreciate the heft of a fine kitchen knife, or the lines of a sports car because the object becomes an extension of you. A Rembrandt, no matter how much you may love or admire it, is never yours. It’s Rembrandt’s. It’s Rembrandt speaking to you over a gulf of time and space. But the men and women who wore these kimono turned themselves into walking works of art.

The exhibition’s earlier works still cling to Japanese design traditions but sneak in an occasional hint of modernity. It’s ironic that Art Nouveau, which profited so mightily from exposure to Japanese export art, was able to effect so little change in the Japanese aesthetic in return. You might see a stylized circular “Mackintosh rose” introduced into a certain design, but for the most part, women’s kimono of the period seemed more resistant to the wholesale appropriation of Western motifs than those worn by their men.

But by the 1920s, with Art Deco roaring in, everything changes and women’s kimono become riots of abstract design and screaming colors. One can only imagine the effect a group of women strolling down the avenue would have made on passers-by. It was probably similar to the impact of mauve on mid-Victorian eyes. Certainly these bold new styles suggested a new type of Japanese woman who had read her Akiko Yosano, made notes in the margins, and was now looking for more of the freedoms enjoyed by her Western sisters.

What militarists prefer on their sleeves

Sadly, the flowering of modernism in post-World War I Japan was as short-lived as the flowering of modernism in post-revolutionary Russia. Militarists and authoritarians of all stripes always seem more comfortable wearing airplanes and battleships on their sleeves than Mackintosh roses. Japan’s increased militancy during the 1930s led to a resolute rejection of all things non-traditional (and thus non-Japanese). Japan’s increasingly desperate situation as World War II wore on resulted in the loss of many kimono, both from bombing raids and relentless austerity drives. (Kimono were literally re-cut into work cloths.)

After the war, Western clothing became the preferred style, and now Kimono are treasured as ceremonial garments and as a part of a national cultural patrimony. This is a wonderful chance for Philadelphians to see these fragile examples of portable beauty. The show’s catalogue is also a knockout and will tell you everything you ever wanted to know about the design and manufacture of kimono.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.