Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

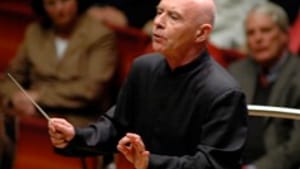

Eschenbach vs. Milanov

Beethoven at the Mann, or:

The great Eschenbach debate continues

TOM PURDOM

How do you stand on the Eschenbach question?

If you write about music in Philadelphia, you’ll be asked about Christoph Eschenbach’s imminent departure at least once or twice a week. It may not be as momentous as the Fracas of the Quarterback Succession, but the Philadelphia Orchestra’s choice of conductor obviously matters to some segments of the local populace.

I have an answer, but I suspect most of my listeners find it unsatisfactory, since it rests, to a large extent, on a purely emotional reaction.

At the end of last season, Eschenbach conducted a pair of ninth symphonies— Shostakovich’s Ninth and the item most of us generally refer to as “the Ninth." A few weeks later, Rossen Milanov conducted the exact same program at the end of the Mann summer season.

The Shostakovich was written at the end of World War II. Stalin expected something triumphant, like the end of the 1812 Overture, but Shostakovich produced a symphony that’s mostly slow and elegiac. The only overt reference to war is a tinny, obviously sarcastic march.

When Milanov conducted the Shostakovich, I realized it was a perfect expression of the feelings I associate with the quiet, sober veterans I met immediately after that war. Shostakovich’s dark music and mocking tin-soldier march captured their somber feelings and their general cynicism about military life and military rituals.

A solid performance vs. a major experience

I heard none of that in Eschenbach’s version. As for Eschenbach’s performance of Beethoven’s Ninth— there was nothing wrong with it, but it lacked the effect the Ninth should convey. The Ninth should be a major experience. I left Verizon Hall feeling I had merely heard a solid performance of a major symphony.

Milanov’s version was a real Ninth. The final movement of that symphony has become one of the great rituals of our civilization, and Milanov shaped it as if he fully understood that.

I had a similar experience with Eschenbach’s version of Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalila symphony. When the Philadelphia Orchestra performed Turangalila for the first time several years ago, it gave me one of the great experiences of my life. Turangalila is probably the ultimate expression of the cosmic vision that runs through all of Messiaen’s work— a vision so broad and compelling that you can respond to it even if you don’t happen to share Messiaen’s Catholic beliefs.

Stopping just short of the summit

I assumed I’d undergo a similar experience when Eschenbach conducted Turangalila a few years ago. Instead, the symphony just sounded loud and clangy.

Eschenbach has delivered some concerts I found totally satisfactory. It’s possible he and I simply possess different temperaments. I can only tell you that the repertoire contains works that are supposed to reach certain emotional and spiritual heights— and that, for me, Eschenbach is a mountaineer who tends to stop just short of the summit.

What Beethoven’s Ninth is supposed to do

This year Milanov opened the Mann season with the Ninth. He paired it with Jennifer Higdon’s Concerto for Orchestra— a piece that made a big splash when the Orchestra premiered it a few years ago.

The Beethoven had its flaws. Milanov pushed the tempo and the choral volume in the final movement and the Philadelphia Singers sounded blarey at important moments. But despite those weaknesses, it was still the Ninth. It did what it’s supposed to do.

Higdon’s Concerto for Orchestra actually sounded better the second time. The first time I heard it, I felt it was a likeable, enjoyable work. This time it sounded deeper and more complex.

The Concerto for Orchestra form has been picked up by a number of composers since Bella Bartok invented it in 1943. Higdon combined it with an older tradition— music composed for specific performers. In this case, the performers were the musicians of the entire Philadelphia Orchestra. All the sections get their moment in the spotlight, along with most of the principals, and Higdon maintains a steady flow of inventions and surprises. Harold Robinson's solo for double bass, for example, breaks without warning into a section that’s devoted to the winds.

This time around, I found the second movement especially striking. The strings play alone the whole time, and they begin with several minutes of tricky rhythmic patterns played pizzicato— an exercise that pushes the string players into the unfamiliar territory normally inhabited by the percussion section.

A no-no by the audience, but….

The Mann audience applauded after every movement. This is supposed to be no-no these days, but it struck me as an appropriate response to the creativity and musical skill displayed on the stage. Audiences did it for Vivaldi and Mozart, and there’s no reason why they shouldn’t do it for Higdon.

I should mention one major complaint about Milanov’s work at this concert. The evening opened with The Star-Spangled Banner, and Milanov conducted it as if he were leading an oompa military march, with a heavy emphasis on the beat instead of the melody line. Wolfgang Sawallisch played it like that, too. It’s supposed to soar, gentlemen. It’s supposed to soar.

The great Eschenbach debate continues

TOM PURDOM

How do you stand on the Eschenbach question?

If you write about music in Philadelphia, you’ll be asked about Christoph Eschenbach’s imminent departure at least once or twice a week. It may not be as momentous as the Fracas of the Quarterback Succession, but the Philadelphia Orchestra’s choice of conductor obviously matters to some segments of the local populace.

I have an answer, but I suspect most of my listeners find it unsatisfactory, since it rests, to a large extent, on a purely emotional reaction.

At the end of last season, Eschenbach conducted a pair of ninth symphonies— Shostakovich’s Ninth and the item most of us generally refer to as “the Ninth." A few weeks later, Rossen Milanov conducted the exact same program at the end of the Mann summer season.

The Shostakovich was written at the end of World War II. Stalin expected something triumphant, like the end of the 1812 Overture, but Shostakovich produced a symphony that’s mostly slow and elegiac. The only overt reference to war is a tinny, obviously sarcastic march.

When Milanov conducted the Shostakovich, I realized it was a perfect expression of the feelings I associate with the quiet, sober veterans I met immediately after that war. Shostakovich’s dark music and mocking tin-soldier march captured their somber feelings and their general cynicism about military life and military rituals.

A solid performance vs. a major experience

I heard none of that in Eschenbach’s version. As for Eschenbach’s performance of Beethoven’s Ninth— there was nothing wrong with it, but it lacked the effect the Ninth should convey. The Ninth should be a major experience. I left Verizon Hall feeling I had merely heard a solid performance of a major symphony.

Milanov’s version was a real Ninth. The final movement of that symphony has become one of the great rituals of our civilization, and Milanov shaped it as if he fully understood that.

I had a similar experience with Eschenbach’s version of Olivier Messiaen’s Turangalila symphony. When the Philadelphia Orchestra performed Turangalila for the first time several years ago, it gave me one of the great experiences of my life. Turangalila is probably the ultimate expression of the cosmic vision that runs through all of Messiaen’s work— a vision so broad and compelling that you can respond to it even if you don’t happen to share Messiaen’s Catholic beliefs.

Stopping just short of the summit

I assumed I’d undergo a similar experience when Eschenbach conducted Turangalila a few years ago. Instead, the symphony just sounded loud and clangy.

Eschenbach has delivered some concerts I found totally satisfactory. It’s possible he and I simply possess different temperaments. I can only tell you that the repertoire contains works that are supposed to reach certain emotional and spiritual heights— and that, for me, Eschenbach is a mountaineer who tends to stop just short of the summit.

What Beethoven’s Ninth is supposed to do

This year Milanov opened the Mann season with the Ninth. He paired it with Jennifer Higdon’s Concerto for Orchestra— a piece that made a big splash when the Orchestra premiered it a few years ago.

The Beethoven had its flaws. Milanov pushed the tempo and the choral volume in the final movement and the Philadelphia Singers sounded blarey at important moments. But despite those weaknesses, it was still the Ninth. It did what it’s supposed to do.

Higdon’s Concerto for Orchestra actually sounded better the second time. The first time I heard it, I felt it was a likeable, enjoyable work. This time it sounded deeper and more complex.

The Concerto for Orchestra form has been picked up by a number of composers since Bella Bartok invented it in 1943. Higdon combined it with an older tradition— music composed for specific performers. In this case, the performers were the musicians of the entire Philadelphia Orchestra. All the sections get their moment in the spotlight, along with most of the principals, and Higdon maintains a steady flow of inventions and surprises. Harold Robinson's solo for double bass, for example, breaks without warning into a section that’s devoted to the winds.

This time around, I found the second movement especially striking. The strings play alone the whole time, and they begin with several minutes of tricky rhythmic patterns played pizzicato— an exercise that pushes the string players into the unfamiliar territory normally inhabited by the percussion section.

A no-no by the audience, but….

The Mann audience applauded after every movement. This is supposed to be no-no these days, but it struck me as an appropriate response to the creativity and musical skill displayed on the stage. Audiences did it for Vivaldi and Mozart, and there’s no reason why they shouldn’t do it for Higdon.

I should mention one major complaint about Milanov’s work at this concert. The evening opened with The Star-Spangled Banner, and Milanov conducted it as if he were leading an oompa military march, with a heavy emphasis on the beat instead of the melody line. Wolfgang Sawallisch played it like that, too. It’s supposed to soar, gentlemen. It’s supposed to soar.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Tom Purdom

Tom Purdom