Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

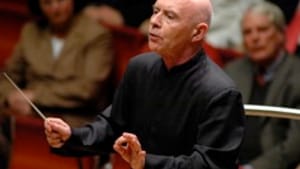

Eschenbach pro and con:

The view from the Inquirer

DAN COREN

In the Sunday Arts & Entertainment section of the September 24th Inquirer, the paper’s two music critics, Peter Dobrin and David Patrick Stearns, debated whether Christoph Eschenbach should stay or go as the Philadelphia Orchestra’s music director when his contract expires in 2009.

Not surprisingly, Dobrin says Eschenbach should leave. As he has from Day One, Dobrin complains about what are, to his ears, Eschenbach’s slipshod performances. But Dobrin’s preponderant argument is that the Orchestra’s musicians didn’t like Eschenbach from the beginning and still don’t. Dobrin compares the relationship between conductor and players to an arranged marriage that hasn’t worked out.

Stearns actually agrees that Eschenbach should leave, but for a different reason: conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra, Stearns contends, just isn’t worth the trouble it entails. But on musical merit alone, Stearns, as has been evident for some time now, more or less agrees with me (and, for what it’s worth, most of my music-loving friends) that Eschenbach, despite his eccentricities, very often elicits profoundly beautiful performances from his players.

Dobrin, one assumes, has access to the Orchestra’s musicians. In fact, he writes as if he spends much of his time enabling musicians’ gripe sessions. But Stearns enjoys the same access; in fact, one of his journalistic strengths over the past year has been his personal interviews with musicians, an approach he obviously relishes. Yet Stearns chooses to make his argument for Eschenbach’s virtues solely on musical terms.

Unless you believe that Stearns and I, and many other people, are delusional and that those magical performances of the Mahler Sixth or the Dvorak Eighth were really disorganized messes, it really doesn’t seem to matter whether or not Eschenbach and his players enjoy an amicable relationship. And why should it? In the 1950s, George Szell in Cleveland and Fritz Reiner in Chicago were famously feared and disliked by their orchestras, but their recordings are legendary. Even if Dobrin is right about those unhappy musicians (and I suspect that his views don’t represent a true consensus of the players’ opinions), Eschenbach is somehow getting his ideas across and getting his musicians to execute them.

For a sports franchise, winning is all that matters. The Orchestra’s ability to produce beautiful performances— not every night, but consistently over time— should, ideally, be the artistic equivalent of fielding a winning team. Surely, by that standard, Eschenbach should be offered another contract. Unfortunately, the Orchestra’s many endemic problems, from labor relationships to an eroding subscriber base, more or less guarantee that this long-running melodrama won’t be resolved on its musical merits.

The view from the Inquirer

DAN COREN

In the Sunday Arts & Entertainment section of the September 24th Inquirer, the paper’s two music critics, Peter Dobrin and David Patrick Stearns, debated whether Christoph Eschenbach should stay or go as the Philadelphia Orchestra’s music director when his contract expires in 2009.

Not surprisingly, Dobrin says Eschenbach should leave. As he has from Day One, Dobrin complains about what are, to his ears, Eschenbach’s slipshod performances. But Dobrin’s preponderant argument is that the Orchestra’s musicians didn’t like Eschenbach from the beginning and still don’t. Dobrin compares the relationship between conductor and players to an arranged marriage that hasn’t worked out.

Stearns actually agrees that Eschenbach should leave, but for a different reason: conducting the Philadelphia Orchestra, Stearns contends, just isn’t worth the trouble it entails. But on musical merit alone, Stearns, as has been evident for some time now, more or less agrees with me (and, for what it’s worth, most of my music-loving friends) that Eschenbach, despite his eccentricities, very often elicits profoundly beautiful performances from his players.

Dobrin, one assumes, has access to the Orchestra’s musicians. In fact, he writes as if he spends much of his time enabling musicians’ gripe sessions. But Stearns enjoys the same access; in fact, one of his journalistic strengths over the past year has been his personal interviews with musicians, an approach he obviously relishes. Yet Stearns chooses to make his argument for Eschenbach’s virtues solely on musical terms.

Unless you believe that Stearns and I, and many other people, are delusional and that those magical performances of the Mahler Sixth or the Dvorak Eighth were really disorganized messes, it really doesn’t seem to matter whether or not Eschenbach and his players enjoy an amicable relationship. And why should it? In the 1950s, George Szell in Cleveland and Fritz Reiner in Chicago were famously feared and disliked by their orchestras, but their recordings are legendary. Even if Dobrin is right about those unhappy musicians (and I suspect that his views don’t represent a true consensus of the players’ opinions), Eschenbach is somehow getting his ideas across and getting his musicians to execute them.

For a sports franchise, winning is all that matters. The Orchestra’s ability to produce beautiful performances— not every night, but consistently over time— should, ideally, be the artistic equivalent of fielding a winning team. Surely, by that standard, Eschenbach should be offered another contract. Unfortunately, the Orchestra’s many endemic problems, from labor relationships to an eroding subscriber base, more or less guarantee that this long-running melodrama won’t be resolved on its musical merits.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Dan Coren

Dan Coren