Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

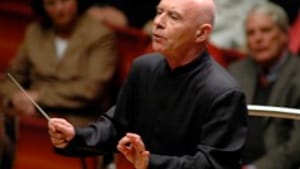

Eschenbach conducts Vivaldi and Bruckner

Eschenbach, Vivaldi, Bruckner:

One of these things doesn't belong

ROBERT ZALLER

Christoph Eschenbach returned this month for his first concerts of the new year with the Philadelphia Orchestra, which are also the last he’ll conduct until the season ends in May— as usual, a month ahead of the New York Philharmonic’s finale. Eschenbach’s program was to have featured Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with the Bruckner Ninth, a thoughtful contrast between the last Romantic masters of the Viennese school. The indisposition of baritone Thomas Quasthoff forced a last-minute cancellation of the Mahler, however. Instead, the Orchestra decided to move up a scheduled performance of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, with soloists from its own ranks for each of the concertos that comprise the score.

Vivaldi and Bruckner don’t jibe at all, of course; they represent not only different styles but different sonic universes. A Mozart or Haydn symphony might have passed muster as a link between the early and late Viennese symphonic tradition, but the Orchestra preferred a showcase for its string section, and a bit of extra rest for the winds and brass. This is why programming is best left to music directors.

In the event, the ensemble playing demonstrated the Orchestra’s usual suavity, but the soloists were a mixed bag. Violinist Paul Roby and concertmaster David Kim made elegant work of the Spring and Winter concertos, but Kimberly Fisher experienced some serious tonal lapses in the opening movement of Summer, and first associate concertmaster Juliette Kang some quirky moments in the outer ones of Autumn. One incidental benefit was a program of European length, with Vivaldi coming in at twice the time of the scheduled Mahler, and Bruckner, with Eschenbach’s spacious tempos, clocking in at just over an hour. For audiences sometimes hustled out of the orchestra’s concerts with barely more than an hour’s music en toto, this was a generous evening, even if an awkwardly juxtaposed one.

Bruckner grapples with Beethoven

Bruckner Ninth’s is one of the summits of the symphonic literature, and perhaps the only 19th-Century score to truly grapple with the legacy of the Beethoven Ninth (Mahler’s Second and Third, in contrast, look beyond it). This does not mean that Bruckner was a traditionalist; on the contrary, he is a staggeringly original artist whose style— not so much assimilated as bypassed by Mahler— is like no one else’s, with its massive sonorities, block-like sections and grinding dissonances. It is the music that the subduction of continents might make, and its sublime impersonality stands at the furthest extreme from Mahler’s febrile expressiveness.

Bruckner is conventionally linked to Wagner, whom he indeed idolized, but he has little to do either with the latter’s sensuality. You must deal with him as you would with a force of nature, one that makes few concessions and insists on being treated on its own terms. For this reason he is accorded more respect than affection. He won’t bring audiences to their feet to cheer, as Mahler does. They are mostly too battered to cheer.

Deep humility or colossal presumption?

Bruckner spent much of his final decade on the Ninth, and worked on it literally until the day of his death. He dedicated it to God, which you may take as indicating either the most colossal presumption or the deepest humility. Perhaps it is best to take it as Bruckner himself apparently did, with perfect seriousness. Deeply devout, he seems to have existed closer to the age of Dante than to his own, and one might not be amiss in hearing in the three completed movements of the Ninth a modern Divine Comedy, with an Infernal first movement (Feierlich, misterioso), a Purgatorial scherzo, and a Paradisal adagio, approaching ever more closely to a vision of the ineffable. Bruckner left sketches for a finale, but if the arch of the work as he conceived it was left incomplete, its height was surely achieved.

The first movement of this performance seemed a bit diffuse, to this listener at least, but the driving rhythms of the Scherzo anchored it, and the Adagio came off with conviction and aplomb. The coming weeks will see a succession of guest conductors, some of them no doubt being auditioned to succeed Eschenbach. If this Ninth is the standard against which they are measured, their work is cut out.

To read a response, click here.

One of these things doesn't belong

ROBERT ZALLER

Christoph Eschenbach returned this month for his first concerts of the new year with the Philadelphia Orchestra, which are also the last he’ll conduct until the season ends in May— as usual, a month ahead of the New York Philharmonic’s finale. Eschenbach’s program was to have featured Mahler’s Kindertotenlieder with the Bruckner Ninth, a thoughtful contrast between the last Romantic masters of the Viennese school. The indisposition of baritone Thomas Quasthoff forced a last-minute cancellation of the Mahler, however. Instead, the Orchestra decided to move up a scheduled performance of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, with soloists from its own ranks for each of the concertos that comprise the score.

Vivaldi and Bruckner don’t jibe at all, of course; they represent not only different styles but different sonic universes. A Mozart or Haydn symphony might have passed muster as a link between the early and late Viennese symphonic tradition, but the Orchestra preferred a showcase for its string section, and a bit of extra rest for the winds and brass. This is why programming is best left to music directors.

In the event, the ensemble playing demonstrated the Orchestra’s usual suavity, but the soloists were a mixed bag. Violinist Paul Roby and concertmaster David Kim made elegant work of the Spring and Winter concertos, but Kimberly Fisher experienced some serious tonal lapses in the opening movement of Summer, and first associate concertmaster Juliette Kang some quirky moments in the outer ones of Autumn. One incidental benefit was a program of European length, with Vivaldi coming in at twice the time of the scheduled Mahler, and Bruckner, with Eschenbach’s spacious tempos, clocking in at just over an hour. For audiences sometimes hustled out of the orchestra’s concerts with barely more than an hour’s music en toto, this was a generous evening, even if an awkwardly juxtaposed one.

Bruckner grapples with Beethoven

Bruckner Ninth’s is one of the summits of the symphonic literature, and perhaps the only 19th-Century score to truly grapple with the legacy of the Beethoven Ninth (Mahler’s Second and Third, in contrast, look beyond it). This does not mean that Bruckner was a traditionalist; on the contrary, he is a staggeringly original artist whose style— not so much assimilated as bypassed by Mahler— is like no one else’s, with its massive sonorities, block-like sections and grinding dissonances. It is the music that the subduction of continents might make, and its sublime impersonality stands at the furthest extreme from Mahler’s febrile expressiveness.

Bruckner is conventionally linked to Wagner, whom he indeed idolized, but he has little to do either with the latter’s sensuality. You must deal with him as you would with a force of nature, one that makes few concessions and insists on being treated on its own terms. For this reason he is accorded more respect than affection. He won’t bring audiences to their feet to cheer, as Mahler does. They are mostly too battered to cheer.

Deep humility or colossal presumption?

Bruckner spent much of his final decade on the Ninth, and worked on it literally until the day of his death. He dedicated it to God, which you may take as indicating either the most colossal presumption or the deepest humility. Perhaps it is best to take it as Bruckner himself apparently did, with perfect seriousness. Deeply devout, he seems to have existed closer to the age of Dante than to his own, and one might not be amiss in hearing in the three completed movements of the Ninth a modern Divine Comedy, with an Infernal first movement (Feierlich, misterioso), a Purgatorial scherzo, and a Paradisal adagio, approaching ever more closely to a vision of the ineffable. Bruckner left sketches for a finale, but if the arch of the work as he conceived it was left incomplete, its height was surely achieved.

The first movement of this performance seemed a bit diffuse, to this listener at least, but the driving rhythms of the Scherzo anchored it, and the Adagio came off with conviction and aplomb. The coming weeks will see a succession of guest conductors, some of them no doubt being auditioned to succeed Eschenbach. If this Ninth is the standard against which they are measured, their work is cut out.

To read a response, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller