Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Up from tyranny

Dolce Suono confronts totalitarianism

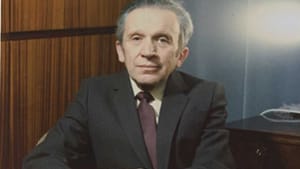

David Finko may be the only contemporary American composer with a lengthy profile in Undersea Warfare, the official magazine of the U.S. Navy’s Submarine Warfare Division. Finko began life in the Soviet Union, as the son of a leading naval engineer, and became an engineer in the Soviet submarine bureaus. There he worked on the hull structures of Soviet nuclear submarines and made several patrols in diesel-electric submarines.

In 1960, at 24, he began studying music and eventually became a composer. In 1979, he emigrated to the U.S. with his family, seeking relief from the oppression endured by all Soviet citizens as well as the additional burdens imposed on Jews. When he applied for emigration, his father, who was dying of cancer, lost his job and all his professional connections.

All the pieces on Dolce Suono’s “Return to Russia” program came with stories, like Finko’s, that connected them to the history of 20th Century totalitarianism. The youngest composer on the roster, Yevgenly Sharlat, arrived in America at 17 with Russian-Jewish parents who were escaping the same privations that harried David Finko. The two best-known composers, Shostakovich and Prokofiev, endured trials familiar to any concertgoer who reads program notes. Their older colleague, Mieczeslaw Weinberg, was a Polish Jew who fled to the Soviet Union to escape the Nazis; he was imprisoned during Russia’s anti-Semitic persecutions in 1953, and Shostakovich risked his life writing a letter in Weinberg’s defense.

Unexpected device

In spite of the fear and oppression the Russian people endured under the commissars, their composers managed to continue a musical tradition noted for its musical inventiveness and emotional appeal. Dolce Suono’s program proved that Russian composers can accomplish this feat even when they limit themselves to a single instrument accompanied by a piano.

Sunday’s centerpiece, for me, was the sonata for viola and piano that Shostakovich finished a few weeks before his death in 1975. It’s a 40-minute marathon for both players, and Burchard Tang and Charles Abramovic gave it a performance worthy of its stature.

The sonata reminds me of Shostakovich’s Second Piano Trio, one of the great chamber works of the 20th Century. Like the Piano Trio, the sonata begins with an unexpected device: a pizzicato passage for the viola. The plucked viola, and the piano background behind it, create the sense, as with the piano trio, that you’re listening to the opening of an epic story.

The rest of the sonata unfolds like a story, without any specific referents. The final adagio leaves you feeling that you’ve been through an important experience— as a good story should.

Shostakovich’s slow movements contain some of his most memorable music; this one includes a melody that sounds like a long love song, followed by a passage for unaccompanied viola that seems saturated with all the yearning the composer could pour into it.

Devastated city

You could hear that same story-telling quality in Finko’s new sonata for flute and piano, which received its premiere at this concert, right after the Shostakovich. In this case, the composer’s notes supplied a story. Finko said he sees the flutist as a protagonist in a “loosely structured narrative.” The opening sequence conceives “a mental picture of a devastated city after a nuclear bombing,” with the flutist as the sole survivor.

I find that notion personally intriguing, since I’ve heard several modern works in which a solo wind instrument sounds, to my mind, like the last instrument on Earth. This is the first time I’ve heard a composer associate his music with the type of imagery that my writerly brain produces.

You need not literally connect this music to nuclear war. The important thing is the general idea of bleakness, accompanied by a movement toward inner peace. The narrative running through the sonata is a personal, inner odyssey, with no hint of melodrama in the music.

All of these pieces shared certain distinctive moods. Finko’s third movement lento evoked a mood I heard in almost all of them: a nostalgic yearning for the sweetly magical moments that dot everyone’s life, whatever their circumstances.

Buried in the archives

The program’s other two flute pieces had stories of their own. Yevgenly Sharlat’s sonata for flute and violin is an early piece he composed for Mimi Stillman’s graduation concert when both of them were students at Curtis. Mieczeslsaw Weinberg’s Five Pieces for Flute and Piano sat in the Russian archives for over 60 years after its premiere in 1948 before it was rediscovered by Bret Werb, the musicologist at the U.S. Holocaust Museum. Mimi Stillman learned about it from Werb while she was researching Dolce Suono’s 2011 Holocaust program; this concert was its American premiere.

The Sharlat sonata supported the flutist with some striking writing for the piano as it showed off Stillman’s tone and technique. The Weinberg includes perky dances, rollicking piano music and a fourth movement that captures the same mood as Finko’s lento.

The Nazis and the Soviets may have persecuted Weinberg because he was Jewish, but there is nothing particularly ethnic about his music. It’s just music anybody can enjoy.

Restless audience

Two hours after the concert began, the audience still hadn’t heard the final work on the program: the first of the three piano sonatas Prokofiev wrote during World War II. About half the audience left before Charles Abramovic sat down at the piano.

Many people probably had to catch trains or honor dinner engagements. But I’m certain a number left because they had absorbed all the music they could digest.

Those who stayed heard a major work played by one of Philadelphia’s best pianists. The Prokofiev sonata is a full half-hour long and just as emotional and demanding as a major piano concerto. It opens with a brutal tumult, but it includes a light, very musical second movement allegro as well as Prokofiev’s version of the gentle nostalgia I heard in the other pieces.

I can understand the feelings of the people who left. There’s a limit to our ability to listen to emotionally intense music. But I can’t think of any entry on the program that could have been omitted. Every piece contributed to an over-all structure— a panorama that covered 75 years of music influenced by a historic disaster.

What, When, Where

Dolce Suono, “Return to Russia”: Sharlat, Sonata for Flute and Piano; Shostakovich, Sonata for Viola and Piano; Finko, Sonata for Flute and Piano; Weinberg, Five Pieces for Flute and Piano; Prokofiev, Sonata for Piano No. 6. Mimi Stillman, flute; Burchard Tang, viola; Charles Abramovic and Tatiana Abramova, piano. December 15, 2013 at Gould Rehearsal Hall, Lenfest Hall, Curtis Institute, 1616 Locust St. (267) 252-1803 or www.dolcesuono.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Tom Purdom

Tom Purdom