Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Viva la (yawn) Revolution

Steven Soderbergh's 'Che'

It comes as no surprise that Steven Soderbergh's two-part epic about the life of Ernesto "Che" Guevara, the Cuban revolution's grim executioner, has provoked worldwide interest, not to mention worldwide protest.

On paper, Guevara's story has the makings of riveting cinema. Che was a courageous and even reckless fighter (as opposed to Castro, who spent most of the revolution secluded in the relative safety of the Sierra Maestra mountains). He was also the dark triggerman of the Cuban Revolution, a fact that Che never concealed and even bragged about, but that most Guevara admirers conveniently ignore.

It was Guevara who executed deserters and captured Batista soldiers and henchmen during the struggle; and it was Guevara who signed many of the tens of thousands of execution orders after the Revolution, when Cuba was bathed in blood by avenging firing squads.

A mother's anguish

According to a story I heard on a Spanish-language radio show in Florida, a Cuban mother once went to beg Che to spare her son's life. The son was 17 and scheduled to be executed within a week. If Guevara pardoned her son, the mother promised, she would see that he never said or did anything against the Revolution.

Che responded by ordering the boy's immediate execution, while the mother was still in his office. His logic: He had spared the mother another week's anguish.

This side of Guevara is absent from four and a half hours of Soderbergh's two films. Unless you're a Guevaraphile and up on your Cuban history, they may put you to sleep. In fact, when I saw Che at the Ritz Five, the bald guy in front of me was asleep most of the time, and the blonde next to me was asleep for about an hour in the first film and most of the second. Those comrades will be reported to the Party.

Disappointing fans and foes alike

If you're a Che fan and accept his myth without its dark side, you may be disappointed as well. Although Soderbergh focuses nearly all his effort on Guevara's humanism and idealism, he declines to glorify or adulate him as past Castro or Che apologists have done.

If you consider Che a cold-blooded murderer, as many people do, then you will wonder why Soderbergh skipped lightly over Che's psychopathic side. We see glimpses of this during Guevara's New York visit, when shouting Cuban exiles call him an assassin and murderer. We also see it in the first film via the rather frigid firing squad execution of two deserters. But Soderbergh never lets us see Che himself pulling the trigger against a deserter or a prisoner, as it has been documented he did 14 times, and as Che himself described.

Soderbergh portrays Che as a champion of the poor, the illiterate and the peasants. Even a light reading of Che's own writing and memoirs would torpedo this simplistic offering of this highly complex figure. A more balanced approach should have included the inexperienced post-revolution bureaucrat who helped to destroy Cuba's middle class, its business infrastructure and its agricultural base, not with his guns but with his incompetence.

Geography lessons

Part One opens with a Cuban geography lesson, mixed with a dizzying array of back-and-forth glimpses of Che and Castro in Mexico (just prior to the revolutionary landing of the yacht Granma in Oriente province), clips of Guevara in the U.S. after the triumph of the Revolution, and endless skirmishes and firefights during the struggle itself.

Part Two opens with a lesson in South American geography, as the story is set in Bolivia: You see, Soderbergh has jumped from the triumph of the Revolution to the end of Che's life. Part Two, I must add, is almost as harrowing an endurance test as surviving Che himself: I witnessed several mass desertions during the screening. Those comrades too will be reported to the Party.

The films also neglect to explore the conflicts between Che and the Castro brothers. The reasons for Che's departure from Cuba are not explored at all.

What's more, Soderbergh perpetuates the false myth that only 12 rebels survived the Granma landing (a story institutionalized by Castro in a heavy-handed attempt to equate the rebels with Christ's disciples).

The Revolution's three Communists

This is one of several historical errors in the films. Another one depicts Vilma Espin, the upper class Communist daughter of a Bacardi executive from Santiago, as one of the original rebels in the mountains. Espin, who soon after the triumph married Raul Castro, was an urban anti-Batista fighter in the streets of Santiago, not in the mountains. She fought under Frank Pais, not Fidel Castro.

Several times Part One depicts the Communists as a strong element of the struggle, which is a serious historical error. Che himself was a declared Communist all along, but other Communists were very rare in the initial ranks of the rebels. After the revolution, Guevara himself remarked that he "only knew of three Communists who had participated in combat."

Castro: the shorter version

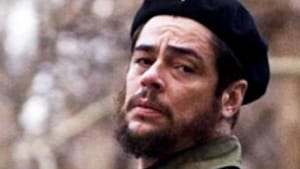

The Puerto Rican actor Benicio del Toro is excellent in the leading role of Che. However, while he effectively conveyed Che's charisma, he seems almost boringly dispassionate in the film's only execution scene.

Mexican actor Demian Bichir delivers an exaggerated Castro, but does so with an excellent mimicking of Castro's odd speaking style. One pedantic issue for me was Bichir's height, which is about the same as del Toro's. The true Fidel Castro capitalized on his towering height when addressing his shorter subordinates.

One supporting actor who stole the limelight in almost every scene that he was in was Venezuelan actor Santiago Cabrera, who played the immense historical part of Camilo Cienfuegos, the iconic, joking, womanizing, charismatic and exceptionally loved Cuban revolutionary. With his ever-present smile, his huge mane of hair and beard, and his big hat, this fun-loving commandante (martyred, probably on the Castro brothers' orders) was portrayed exceptionally well by Cabrera.

A slight problem in Bolivia

Che went to Bolivia (the film's Part Two) to export revolution to the Americas. But his guerrilla band never numbered more than 51 men, including 17 experienced Cubans who held nearly all the command positions but were unable to speak the language of the indigenous local Indians. The film portrays them as humanistic benefactors of the locals, but as Che noted in his diaries, the local peasants were "as impenetrable as rocks." This inability to "penetrate" them doomed the Bolivian expedition.

I was also disappointed by the lack of development of the character of Tania (played by German actress Franka Potente), an East German KGB agent sent to Havana by the Soviets to keep tabs on Che. When she was killed in combat in Bolivia, she was four months pregnant with Guevara's child.

None of these interesting historical facts is explored in Part Two— not that I want to extend its length, but a little less fighting and a little more character development would have helped. Or maybe not.

On paper, Guevara's story has the makings of riveting cinema. Che was a courageous and even reckless fighter (as opposed to Castro, who spent most of the revolution secluded in the relative safety of the Sierra Maestra mountains). He was also the dark triggerman of the Cuban Revolution, a fact that Che never concealed and even bragged about, but that most Guevara admirers conveniently ignore.

It was Guevara who executed deserters and captured Batista soldiers and henchmen during the struggle; and it was Guevara who signed many of the tens of thousands of execution orders after the Revolution, when Cuba was bathed in blood by avenging firing squads.

A mother's anguish

According to a story I heard on a Spanish-language radio show in Florida, a Cuban mother once went to beg Che to spare her son's life. The son was 17 and scheduled to be executed within a week. If Guevara pardoned her son, the mother promised, she would see that he never said or did anything against the Revolution.

Che responded by ordering the boy's immediate execution, while the mother was still in his office. His logic: He had spared the mother another week's anguish.

This side of Guevara is absent from four and a half hours of Soderbergh's two films. Unless you're a Guevaraphile and up on your Cuban history, they may put you to sleep. In fact, when I saw Che at the Ritz Five, the bald guy in front of me was asleep most of the time, and the blonde next to me was asleep for about an hour in the first film and most of the second. Those comrades will be reported to the Party.

Disappointing fans and foes alike

If you're a Che fan and accept his myth without its dark side, you may be disappointed as well. Although Soderbergh focuses nearly all his effort on Guevara's humanism and idealism, he declines to glorify or adulate him as past Castro or Che apologists have done.

If you consider Che a cold-blooded murderer, as many people do, then you will wonder why Soderbergh skipped lightly over Che's psychopathic side. We see glimpses of this during Guevara's New York visit, when shouting Cuban exiles call him an assassin and murderer. We also see it in the first film via the rather frigid firing squad execution of two deserters. But Soderbergh never lets us see Che himself pulling the trigger against a deserter or a prisoner, as it has been documented he did 14 times, and as Che himself described.

Soderbergh portrays Che as a champion of the poor, the illiterate and the peasants. Even a light reading of Che's own writing and memoirs would torpedo this simplistic offering of this highly complex figure. A more balanced approach should have included the inexperienced post-revolution bureaucrat who helped to destroy Cuba's middle class, its business infrastructure and its agricultural base, not with his guns but with his incompetence.

Geography lessons

Part One opens with a Cuban geography lesson, mixed with a dizzying array of back-and-forth glimpses of Che and Castro in Mexico (just prior to the revolutionary landing of the yacht Granma in Oriente province), clips of Guevara in the U.S. after the triumph of the Revolution, and endless skirmishes and firefights during the struggle itself.

Part Two opens with a lesson in South American geography, as the story is set in Bolivia: You see, Soderbergh has jumped from the triumph of the Revolution to the end of Che's life. Part Two, I must add, is almost as harrowing an endurance test as surviving Che himself: I witnessed several mass desertions during the screening. Those comrades too will be reported to the Party.

The films also neglect to explore the conflicts between Che and the Castro brothers. The reasons for Che's departure from Cuba are not explored at all.

What's more, Soderbergh perpetuates the false myth that only 12 rebels survived the Granma landing (a story institutionalized by Castro in a heavy-handed attempt to equate the rebels with Christ's disciples).

The Revolution's three Communists

This is one of several historical errors in the films. Another one depicts Vilma Espin, the upper class Communist daughter of a Bacardi executive from Santiago, as one of the original rebels in the mountains. Espin, who soon after the triumph married Raul Castro, was an urban anti-Batista fighter in the streets of Santiago, not in the mountains. She fought under Frank Pais, not Fidel Castro.

Several times Part One depicts the Communists as a strong element of the struggle, which is a serious historical error. Che himself was a declared Communist all along, but other Communists were very rare in the initial ranks of the rebels. After the revolution, Guevara himself remarked that he "only knew of three Communists who had participated in combat."

Castro: the shorter version

The Puerto Rican actor Benicio del Toro is excellent in the leading role of Che. However, while he effectively conveyed Che's charisma, he seems almost boringly dispassionate in the film's only execution scene.

Mexican actor Demian Bichir delivers an exaggerated Castro, but does so with an excellent mimicking of Castro's odd speaking style. One pedantic issue for me was Bichir's height, which is about the same as del Toro's. The true Fidel Castro capitalized on his towering height when addressing his shorter subordinates.

One supporting actor who stole the limelight in almost every scene that he was in was Venezuelan actor Santiago Cabrera, who played the immense historical part of Camilo Cienfuegos, the iconic, joking, womanizing, charismatic and exceptionally loved Cuban revolutionary. With his ever-present smile, his huge mane of hair and beard, and his big hat, this fun-loving commandante (martyred, probably on the Castro brothers' orders) was portrayed exceptionally well by Cabrera.

A slight problem in Bolivia

Che went to Bolivia (the film's Part Two) to export revolution to the Americas. But his guerrilla band never numbered more than 51 men, including 17 experienced Cubans who held nearly all the command positions but were unable to speak the language of the indigenous local Indians. The film portrays them as humanistic benefactors of the locals, but as Che noted in his diaries, the local peasants were "as impenetrable as rocks." This inability to "penetrate" them doomed the Bolivian expedition.

I was also disappointed by the lack of development of the character of Tania (played by German actress Franka Potente), an East German KGB agent sent to Havana by the Soviets to keep tabs on Che. When she was killed in combat in Bolivia, she was four months pregnant with Guevara's child.

None of these interesting historical facts is explored in Part Two— not that I want to extend its length, but a little less fighting and a little more character development would have helped. Or maybe not.

What, When, Where

Che. A film by Steven Soderbergh. At the Ritz Five, 214 Walnut St. (215) 925-7900 or www.landmarktheatres.com/Market/Philadelphia/Philadelphia_Frameset.htm.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

F. Lennox Campello

F. Lennox Campello