Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

From North Philly to Renaissance Italy

"Birth of the Cool': Barkley Hendricks at Pennsylvania Academy

Although it's billed as a retrospective, "Birth of the Cool" actually focuses mostly on the early work of the North Philadelphia native Barkley Hendricks. The vast majority of the paintings in this show were done during the '60s and '70s, including Hendricks's student years at the Pennsylvania Academy (1963-1967) and at Yale, where he earned a BFA and an MFA.

While at the Academy, Hendricks was awarded two travel grants. With the first he went to Italy, and with the second he went to North Africa. Although the latter trip influenced the strong political undertones of much of his work, the visual effect of his time in Italy is more immediately striking.

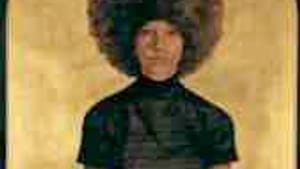

Some of Hendricks's early work conducts a direct conversation with the Byzantine art he studied in Italy. In Lawdy Mama and Icon for My Man Superman (both 1969), he painted modern figures in stylized poses against metallic backgrounds. Hendricks returns to this visual style more flamboyantly in Fela: Amen, Amen, Amen (2002), a portrait of the late Nigerian musician/activist/politician Fela Kuti.

I dress, therefore I am

In between these overtly iconic images, Hendricks produced a substantial body of portraiture. His subjects were urban people of color, whom he painted full-size, full-length. The poses, as well as the featureless backgrounds Hendricks favored, evoke the work of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, photographers who shot both portraits and fashion work, often working in similar ways in both genres.

Hendricks's subjects were fashionably dressed and posed in ways that emphasize how their clothing serves as a primary channel in their presentation of self. In fact, Hendricks often chose his subjects because of their dress — he would see someone on the street and ask to photograph him or her, working from those photographs later.

Despite the modern gloss, though, the underlying influence of Hendricks's Byzantine inspiration is clear. The figures are limned clearly against monochromatic backgrounds, often the same color as the dominant image, creating an overall flatness of plane. The bodies of the subjects are also presented as though in a series of flat planes. This effect is most striking in the works with multiple figures, like What's Goin' On (1974), but it's there in most of the portraits.

Tactile surfaces

What makes this Byzantine flatness so interesting is the way Hendricks treats each of the planes. Revealing the other lasting influence from his student days— the Italian Renaissance— Hendricks goes to great pains to convey the tactility of surfaces: fabrics, jewelry, skin. In North Philly Niggah (1975), the subject's peach-colored coat glows with an almost translucent effect against the slightly paler peach of the background. (And, yes, each time Hendricks uses the word niggah in a title, the painting's label explains it, repeating the same carefully phrased words.)

This sensuousness extends to the visual properties of materials. Hendricks pays loving attention to reflections: on a pair of sunglasses, a silver bracelet, a shiny bald head. (This fascination starts early: a self-portrait from his Pennsylvania Academy days includes light reflected off the glasses he was wearing.)

In addition to the '60s and '70s portraits, the show features a dozen or so plein air landscapes painted in Jamaica over the past decade. These are the opposite of the Hendricks portraits in every way, starting with subject matter, of course, and mood, since they're immediate responses, not meticulously worked effects. They're intimate in scale, at a couple of feet across, unlike the assertively sized portraits.

The presentation is different as well: In another nod to the Italian Renaissance, the ovals, circles and lunettes of the landscapes are elaborately framed. The contrast is refreshing, and yet the deeper connection of influence is there.♦

To read a response, click here.

While at the Academy, Hendricks was awarded two travel grants. With the first he went to Italy, and with the second he went to North Africa. Although the latter trip influenced the strong political undertones of much of his work, the visual effect of his time in Italy is more immediately striking.

Some of Hendricks's early work conducts a direct conversation with the Byzantine art he studied in Italy. In Lawdy Mama and Icon for My Man Superman (both 1969), he painted modern figures in stylized poses against metallic backgrounds. Hendricks returns to this visual style more flamboyantly in Fela: Amen, Amen, Amen (2002), a portrait of the late Nigerian musician/activist/politician Fela Kuti.

I dress, therefore I am

In between these overtly iconic images, Hendricks produced a substantial body of portraiture. His subjects were urban people of color, whom he painted full-size, full-length. The poses, as well as the featureless backgrounds Hendricks favored, evoke the work of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, photographers who shot both portraits and fashion work, often working in similar ways in both genres.

Hendricks's subjects were fashionably dressed and posed in ways that emphasize how their clothing serves as a primary channel in their presentation of self. In fact, Hendricks often chose his subjects because of their dress — he would see someone on the street and ask to photograph him or her, working from those photographs later.

Despite the modern gloss, though, the underlying influence of Hendricks's Byzantine inspiration is clear. The figures are limned clearly against monochromatic backgrounds, often the same color as the dominant image, creating an overall flatness of plane. The bodies of the subjects are also presented as though in a series of flat planes. This effect is most striking in the works with multiple figures, like What's Goin' On (1974), but it's there in most of the portraits.

Tactile surfaces

What makes this Byzantine flatness so interesting is the way Hendricks treats each of the planes. Revealing the other lasting influence from his student days— the Italian Renaissance— Hendricks goes to great pains to convey the tactility of surfaces: fabrics, jewelry, skin. In North Philly Niggah (1975), the subject's peach-colored coat glows with an almost translucent effect against the slightly paler peach of the background. (And, yes, each time Hendricks uses the word niggah in a title, the painting's label explains it, repeating the same carefully phrased words.)

This sensuousness extends to the visual properties of materials. Hendricks pays loving attention to reflections: on a pair of sunglasses, a silver bracelet, a shiny bald head. (This fascination starts early: a self-portrait from his Pennsylvania Academy days includes light reflected off the glasses he was wearing.)

In addition to the '60s and '70s portraits, the show features a dozen or so plein air landscapes painted in Jamaica over the past decade. These are the opposite of the Hendricks portraits in every way, starting with subject matter, of course, and mood, since they're immediate responses, not meticulously worked effects. They're intimate in scale, at a couple of feet across, unlike the assertively sized portraits.

The presentation is different as well: In another nod to the Italian Renaissance, the ovals, circles and lunettes of the landscapes are elaborately framed. The contrast is refreshing, and yet the deeper connection of influence is there.♦

To read a response, click here.

What, When, Where

Barkley L. Hendricks: “Birth of the Cool.†Through January 3, 2010 at Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Hamilton Bldg., Broad and Cherry Sts. (215) 972-7600 or www.pafa.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Judy Weightman

Judy Weightman