Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

How not to make a movie

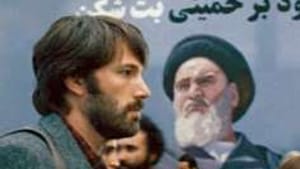

Ben Affleck's "Argo': CIA in Iran

Whatever happened to Ben Affleck? The actor who rocketed to fame with best friend and tenth cousin Matt Damon in Good Will Hunting, disappeared into such disasters as Gigli and Surviving Christmas, and dined out on a number of crash-and-burn high profile Hollywood romances, hasn't actually been that far away, but his career has certainly been a mixed bag.

Affleck's actor-director turn in Argo, a film about the rescue of six Americans who escaped capture during the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979, has made him a hot property again. But how good is his film? How does its story speak to us today?

Argo operates on three levels, with varying degrees of success. It's a re-enactment of an actual event, and so a piece of historical reconstruction. Its story line contains all the ingredients of a standard Hollywood action flick: innocents abroad, threatened by bad guys and rescued by a lone wolf hero in the face of bureaucratic resistance.

It's also a story about Hollywood filmmaking itself, because the story's central element is the faked production of a sci-fi thriller called Argo that serves as the pretext for the rescue operation. So Argo is, on this level, a film about a film called Argo that was never made.

Orson Welles in heaven

If you don't read the trades, your information about what Hollywood's cooking up next usually comes from trailers or commercial ads. But Tinseltown is littered with scripts that die a-borning, collapse at the last minute (the star dies; the financing goes belly-up), or lie on the shelf without ever being produced. In some alternative universe, all of Orson Welles's unfinished projects become actual masterpieces; and if there's a heaven for film buffs, we'll get to see them when we enter the great beyond.

Of course, most film projects don't pan out for a more prosaic reason: They're terrible ideas to begin with.

(If you go to the movies with any regularity, you know that plenty of terrible films do wind up at the Cineplex. We're talking not about the laws of natural selection here, but something more like stochastic randomness.)

Inspired by TV

The best part of Argo is the film-within-a-film about a film that was never made. Tony Mendez (played by Affleck himself), a CIA operative with low-level Hollywood contacts, comes up with the idea of sneaking out the American escapees, who have secretly taken refuge in the Canadian embassy, by passing them off as members of a film crew scouting locations. Specifically, the idea comes to him when he watches Planet of the Apes on TV (some things are too bizarre to be made up).

Tony's superiors naturally shoot down this idea, but they can't come up with a better one. Meanwhile, the clock is ticking on a second disaster that could turn out to be worse than the first.

Not making a movie is easier said than done. To pass muster with the Iranians, the project must be credible within the Hollywood community itself; that is, it needs an actual script, a production office, and a cast.

Lampooning the CIA

Tony calls on John Chambers (John Goodman), a designer and a fixer, who in turn prevails on a schlockmeister producer, the invented character of Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin). Between them, they find the script, secure the rights, storyboard the action and set up the phony operation as a Canadian production.

Goodman is outlandishly hilarious in his role, and Arkin slyly so. As a bit of inside baseball on the business of movie making, this is dead-on satire, and clearly the part of the film Affleck attacked with most relish. He has some fun too at the CIA's expense. But when Affleck must get back to the plot, the flag goes up.

Good guys gone bad

The film opens with a potted history of U.S.-Iranian relations up to the 1979 revolution, in which it's duly noted that a democratically elected nationalist leader, Mohammed Mossadegh, had been ousted in 1953 in a CIA-sponsored coup, and the country subjected to a quarter-century of authoritarian monarchy to ensure Western access to Iranian oil and a secure base against Communism. The revolution that overthrew the Shah of Iran thus appeared as a legitimate restoration of freedom, and many in the West, particularly on the left, took it as such.

That perception changed abruptly on November 4, 1979, when the U.S. embassy in Teheran was stormed and 44 members of its staff were paraded blindfolded as hostages. The good guys became bad ones in the space of that day, and our national obsession over the next 14 months would be the recovery of the hostages.

The six escapees were the only Americans to be rescued under Jimmy Carter— small thanks to the White House, which reluctantly signed on to the Mendez mission and almost scuttled it at the last minute.

Swinging corpse

Like American public opinion, Affleck's film also turns on a dime at this point. We see the embassy staff frantically shredding documents (which would presumably detail the close relationship between the U.S. government and the Shah) as an angry crowd approaches.

But our attention soon turns to the sextet of refugees, which include two winsome young couples, and their kindly if somewhat nonplussed Canadian hosts. Clearly, the embassy is an outpost of sanity in a revolution gone amok, as we're reminded by a hanged corpse swaying in midair from a steel girder.

In a further scene (also invented), Mendez leads the terrified Americans through a marketplace in which they're surrounded and finally beset on all sides by hostile natives. Presumably, they make this foray to establish their bona fides as a scouting crew, although exactly what role a packed Middle Eastern market could play in a sci-fi movie remains unexplained. The more likely point of this episode is to further our identification with the trapped Americans, as well as our sense of Iran as a country gone mad.

Dangerous fanatics?

Affleck also juices up the escape itself, inserting an imaginary attempt to block the takeoff of the Swissair jet carrying the Americans to freedom. This is poetic license, to be sure, and it adds to the tension (if not the credibility) of the actual escape.

But it also underscores the film's ideological point: Iranians may be gullible enough to fall for a cockeyed ruse, but by the same token they're dangerous fanatics who must be finally dealt with as savages. In the present political climate, in which war with Iran is being openly discussed and already covertly waged, Argo, its opening disclaimer notwithstanding, beats the drums.

A much cooler view of the escape, building on the satire of the fake Argo and the semi-absurdity of the rescue plot, might have contributed to putting present Iranian-American relations in context rather than further polarizing them. Billy Wilder or Stanley Kubrick might have made such a movie. Ben Affleck starts off on it, but soon reverts to Hollywood formula.

Affleck has been associated with various liberal causes and political candidates. But when the chips— i.e., the calculations of box office— were down, he opted to reprise his Jack Ryan role in The Sum of All Fears, albeit in a softer mode. The only takeaway you need is that the good guys won, and that the CIA finally protects us all.

Affleck's actor-director turn in Argo, a film about the rescue of six Americans who escaped capture during the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979, has made him a hot property again. But how good is his film? How does its story speak to us today?

Argo operates on three levels, with varying degrees of success. It's a re-enactment of an actual event, and so a piece of historical reconstruction. Its story line contains all the ingredients of a standard Hollywood action flick: innocents abroad, threatened by bad guys and rescued by a lone wolf hero in the face of bureaucratic resistance.

It's also a story about Hollywood filmmaking itself, because the story's central element is the faked production of a sci-fi thriller called Argo that serves as the pretext for the rescue operation. So Argo is, on this level, a film about a film called Argo that was never made.

Orson Welles in heaven

If you don't read the trades, your information about what Hollywood's cooking up next usually comes from trailers or commercial ads. But Tinseltown is littered with scripts that die a-borning, collapse at the last minute (the star dies; the financing goes belly-up), or lie on the shelf without ever being produced. In some alternative universe, all of Orson Welles's unfinished projects become actual masterpieces; and if there's a heaven for film buffs, we'll get to see them when we enter the great beyond.

Of course, most film projects don't pan out for a more prosaic reason: They're terrible ideas to begin with.

(If you go to the movies with any regularity, you know that plenty of terrible films do wind up at the Cineplex. We're talking not about the laws of natural selection here, but something more like stochastic randomness.)

Inspired by TV

The best part of Argo is the film-within-a-film about a film that was never made. Tony Mendez (played by Affleck himself), a CIA operative with low-level Hollywood contacts, comes up with the idea of sneaking out the American escapees, who have secretly taken refuge in the Canadian embassy, by passing them off as members of a film crew scouting locations. Specifically, the idea comes to him when he watches Planet of the Apes on TV (some things are too bizarre to be made up).

Tony's superiors naturally shoot down this idea, but they can't come up with a better one. Meanwhile, the clock is ticking on a second disaster that could turn out to be worse than the first.

Not making a movie is easier said than done. To pass muster with the Iranians, the project must be credible within the Hollywood community itself; that is, it needs an actual script, a production office, and a cast.

Lampooning the CIA

Tony calls on John Chambers (John Goodman), a designer and a fixer, who in turn prevails on a schlockmeister producer, the invented character of Lester Siegel (Alan Arkin). Between them, they find the script, secure the rights, storyboard the action and set up the phony operation as a Canadian production.

Goodman is outlandishly hilarious in his role, and Arkin slyly so. As a bit of inside baseball on the business of movie making, this is dead-on satire, and clearly the part of the film Affleck attacked with most relish. He has some fun too at the CIA's expense. But when Affleck must get back to the plot, the flag goes up.

Good guys gone bad

The film opens with a potted history of U.S.-Iranian relations up to the 1979 revolution, in which it's duly noted that a democratically elected nationalist leader, Mohammed Mossadegh, had been ousted in 1953 in a CIA-sponsored coup, and the country subjected to a quarter-century of authoritarian monarchy to ensure Western access to Iranian oil and a secure base against Communism. The revolution that overthrew the Shah of Iran thus appeared as a legitimate restoration of freedom, and many in the West, particularly on the left, took it as such.

That perception changed abruptly on November 4, 1979, when the U.S. embassy in Teheran was stormed and 44 members of its staff were paraded blindfolded as hostages. The good guys became bad ones in the space of that day, and our national obsession over the next 14 months would be the recovery of the hostages.

The six escapees were the only Americans to be rescued under Jimmy Carter— small thanks to the White House, which reluctantly signed on to the Mendez mission and almost scuttled it at the last minute.

Swinging corpse

Like American public opinion, Affleck's film also turns on a dime at this point. We see the embassy staff frantically shredding documents (which would presumably detail the close relationship between the U.S. government and the Shah) as an angry crowd approaches.

But our attention soon turns to the sextet of refugees, which include two winsome young couples, and their kindly if somewhat nonplussed Canadian hosts. Clearly, the embassy is an outpost of sanity in a revolution gone amok, as we're reminded by a hanged corpse swaying in midair from a steel girder.

In a further scene (also invented), Mendez leads the terrified Americans through a marketplace in which they're surrounded and finally beset on all sides by hostile natives. Presumably, they make this foray to establish their bona fides as a scouting crew, although exactly what role a packed Middle Eastern market could play in a sci-fi movie remains unexplained. The more likely point of this episode is to further our identification with the trapped Americans, as well as our sense of Iran as a country gone mad.

Dangerous fanatics?

Affleck also juices up the escape itself, inserting an imaginary attempt to block the takeoff of the Swissair jet carrying the Americans to freedom. This is poetic license, to be sure, and it adds to the tension (if not the credibility) of the actual escape.

But it also underscores the film's ideological point: Iranians may be gullible enough to fall for a cockeyed ruse, but by the same token they're dangerous fanatics who must be finally dealt with as savages. In the present political climate, in which war with Iran is being openly discussed and already covertly waged, Argo, its opening disclaimer notwithstanding, beats the drums.

A much cooler view of the escape, building on the satire of the fake Argo and the semi-absurdity of the rescue plot, might have contributed to putting present Iranian-American relations in context rather than further polarizing them. Billy Wilder or Stanley Kubrick might have made such a movie. Ben Affleck starts off on it, but soon reverts to Hollywood formula.

Affleck has been associated with various liberal causes and political candidates. But when the chips— i.e., the calculations of box office— were down, he opted to reprise his Jack Ryan role in The Sum of All Fears, albeit in a softer mode. The only takeaway you need is that the good guys won, and that the CIA finally protects us all.

What, When, Where

Argo. A film directed by Ben Affleck. For Philadelphia area show times, click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller