Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Art Museum's Wyeth show

Andrew Wyeth:

The something inside the nothing

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

My God, when you really begin to see into something, a simple object, and realize the profound meaning of that thing—if you have an emotion about it, there's no end.

—Andrew Wyeth

One of the peculiar things about Modernism was its tendency to cast stones and to keep on casting them until a particular bête noir was dead. Thus it came about that artists who worked within a figurative tradition were roundly denounced as passé. They were ignored or willfully misunderstood, and so it came about that Andrew Wyeth was viewed as a realist—a camera attached to a brush stuck in front of a canvas— and no one bothered to ask such interesting questions as: Why does he paint so many empty spaces?

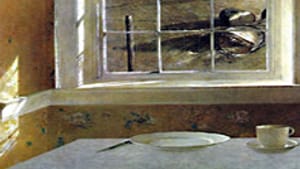

Here is an artist who titles a view of an empty landscape seen through an open window Love In the Afternoon. Clearly, any love going on must be occurring on the other side of that open window, right? Right— unless, of course, the painter is referring to his love of solitude and the broad "empty" landscape he presents to us.

Wyeth goes down better as you grow older. At 25, I was intensely impatient with the Sage of Chadds Ford. As far as I was concerned, the landscape was ugly, the people were plain, and that was that. Oddly enough, my feelings about Wyeth began to change when, on a whim, I purchased a second-hand copy of the book of his ”Helga” pictures. There are two ways to view the Helga paintings—they are either a classy collection of nudies, or they’re about something else. Technique, perhaps? Yes, Wyeth used a variety of techniques to obtain different effects. But there’s more to the Helga paintings. You look at them and you want to know more—more about subject (what's going on in her mind?), more about the artist (what is he thinking? What is he trying to say?).

Wyeth was the scion of a great tradition in book illustration. The achievements of Howard Pyle and his own father, N.C. Wyeth, were always before him. But what does a really good book illustration do? (Hint: it doesn't necessary describe the events in the text.) Great illustrations raise questions in your mind; they force you to look deeper, to read more into the words.

The uncanny effect of an empty room

I think that I've grown up enough to understand what Wyeth is getting at. It's taken me 30 years, but I can understand now the uncanny effect an empty room can exert. Widow's Walk, where the upper-story windows of the house look like eyes, still strikes me as Wyeth sojourning in Edward-Hopper-Land (he goes there sometimes). But Renfield—in which we see the interior of the same structure— becomes magical. Even the title—Wyeth named the work after Count Dracula's fly- and spider-eating servant— becomes evocative of isolation and strangeness, but with a hint of black humor—there must be lots of flies and spiders up there for Renfield to munch on. But then it turns serious again: Renfield eats the spiders and flies to absorb their souls. Is Wyeth referring perhaps to the souls of the generations of dead widows who must have walked up there? Have they been swallowed up in this empty space?

Interestingly, the Art Museum’s current exhibition offers two "making of" series in which we see the way Wyeth's ultimate vision emerges. He sets out to depict his old fisherman pal Walt Anderson inside his cottage. But as Wyeth continues to restate the idea, Anderson retreats into the background and finally comes to be represented by nothing more than his empty boots. In Sea Boots, the final version of the work, the empty boots stand in the sand with Anderson's house visible in the background. Mere words don't do the image justice. Anderson's house is reduced to its peaked roof looming above the gray sands like a pyramid. Anderson's boots appear to stand in a desert, and the resultant image is both grandiose and homely. It's like a salute to Beau Geste and The Four Feathers. (Remember— this is N.C. Wyeth's boy.)

The series revolving around the creation of Groundhog Day tells a similar tale. What began as a depiction of Anna Kuerner sitting in her kitchen becomes, in a final incarnation, an image of a sun-washed empty room. Shades of Renfield!

Clearly, then, Renfield is not unique in Wyeth's oeuvre. He also painted The Witching Hour and Two If By Sea, and in each case it can be said that he makes "something out of nothing.” But the truth is that Wyeth actually sees the something that abides within the nothing. In short, Wyeth is an American mystic, although I think this term would probably make him uncomfortable. Yet as his own words at the head of this essay attest, Wyeth recognizes that "there's no end" once you realize the meaning of a thing. It's interesting that as America went on a binge of materialism, we pigeonholed this unique personality as a simple recorder of everyday life. As a people, we forgot how to see. Fortunately for us, there are always the Wyeths among who remember, and as Wyeth himself has said: "If a painting is good, it's mostly memory."

A short tour of the Art Museum show

"Andrew Wyeth: Memory and Magic" is a fairly extensive show, so I'll endeavor to take you on my own short tour of it.

As you enter, you are confronted by Trodden Weed, a tempera on panel in which we see a pair of sturdy boots and a hint of a dark coat caught in mid-stride. It seems almost whimsical—like one of those family snapshots where Uncle Ernie cuts people off at the knees. The painting means much more to Wyeth, who points out that the feet (they are his own) are heedlessly trampling down the weed, which for its weedness is still a living thing. Wyeth is talking about man's heedlessness in the face of Nature. But even if you don't know that, even if you don't know that this curious work is something of a self-portrait, it still seems like a typical production from Wyeth the Sage. But then you turn a corner and find yourself confronted by…

Breakup (1994). Say whaa? This is Andrew Wyeth? What are we to make of those blackened claw-like hands impossibly thrusting out of an ice floe? Clearly, there's more to Wyeth than "photographic realism." This little work should put you on your guard against underestimating this artist.

The Lobsterman (1937) is an early Wyeth watercolor that looks amazingly like a Winslow Homer watercolor. Wyeth visited Homer's Prout's Neck studio in Maine, and he clearly didn't go there as a tourist.

Adrift (1982) depicts Walt Anderson, Wyeth’s old Maine friend, asleep in a drifting rowboat. It does suggest (1) death and (2) a Viking funeral—which, as it happens, is exactly what the artist wanted us to take away from the image. Now, some folks may feel that an artist who possesses "the common touch" is common—but I'll still take Adrift over a stack of abstract paintings.

Wind from the Sea (1947). The wind billowing window curtains is always an evocative image. Edward Hopper did something similar in his etching Evening Wind, and even John Huston used it for mood in a scene from his film The Maltese Falcon. But Wyeth saw his billowing curtains as representing the feminine presence of Christina Olsen. I suspect that Hopper just liked the starkness of the scene.

Quaker Ladies (1956). Is Wyeth a "poetic" observer of Nature, à la Ruisdael, or is there something more? Is this what he feels, or what his mind reads into it?

The eerie quality of silent snow

First Snow (Study for Groundhog Day, 1959). Call me an idiot, but I prefer the study to the finished work. Wyeth captures absolutely and for all time the eerie quality of silence that accompanies a fresh snowfall.

Public Sale (1943). This is certainly a crowd-pleasing work of realism, but consider for a moment how the painting's Cinemascope format influences our perception of it. The vertiginously-tilted point-of-view— it could almost be the view enjoyed by one of Wyeth's soaring ravens— and wide focus suggests another, cosmic drama taking place beyond this gathering of farmers to purchase a dead neighbor's belongings. Consider the importance of the season. Of course it's parochial, Symbolism 101, to link winter with death— but would it have worked as well in the summer? Clearly, the neighbor could have died as easily in July as in January. And unless Wyeth set out to create a visually exact memorial of what occurred that day, he could as easily have set his work in the summer as in winter. But as the finished work stands, the starkness of the landscape, the restricted palette of colors, the expanses of sky and land all work together to create a powerful statement on the theme of the vanity of all human endeavors.

Soaring (1942-50). It took Wyeth eight years to create this large tempera painting of ravens in flight, and it's quite an image. It's as accessible as a Disney cartoon and as strange as the very notion of flight. You can get dizzy if you stare at this one long enough.

Take a closer look

Winter (1946). This is the signature image for the show, and it's a good choice because, like Renfield, it puts you through changes. First impression: nice, homey Americana, a country boy racing through a field. But look closer: The mood is grim rather than carefree. The colors are somber. The boy seems distressed. Look closer: The "boy" could be anywhere from 12 to 40. He could well be a man. He could even be Wyeth himself. In fact, Winter arose out of Wyeth's sense of aloneness in the wake of the shocking death of his father. He was not a happy artist at the time, and Winter is not the happy, carefree image it may first appear to be.

Christmas Morning (1944). Here we see Wyeth working in an unfamiliar "surrealist" mode. Think back to Breakup, which almost opens the show. Wyeth is not Sergeant Friday of Dragnet ("Just the fact, ma'am."). But he's not Salvador Dali either, and he works best with a light touch. Christmas Morning seems too obviously poetic to me to succeed as poetry. But the painting proves the extent to which surrealism was in the artistic air in the 1940s.

Faraway (1952). This is a famous image; and the boy— Wyeth's son Jamie, sitting hunched in a field wearing his spiffy Davy Crockett coonskin cap— is an archetypal image of a child's imagination at work.

Buildings have personalities, too

River Cove (1958). The "message" of this large tempera painting is lost on city boys like me. Wyeth wants us to see those delicate tracks left in the sand by a passing heron. But the beauty is all too transient, and the rising tide will erase the bird's tracks. Wyeth himself has gone on record thusly: "Nature is not lyrical and nice. Behind the peace is violence."

Brown Swiss (1957) Another Cinemascope composition. This time Wyeth creates an interesting mood by pushing the Kuerner farmhouse to the extreme left of the painting— almost as though it were attempting to evade our glances— thus accenting the land's brown expanse. Wyeth believes that buildings have personalities of their own—something that only a real estate developer would dispute— and the Kuerner house seems to be fighting just to hang on. The painting is named for the type of cow that Kuerner kept in the empty pasture.

Finally, I also want to call your attention to a wonderful pair of nature painting that date from early in Wyeth's career. Winter Fields (1942) and Blackberry Picker (1943) are works of their time— dark, romantic, looking back on the 19th-Century Hudson Valley and Pre-Raphaelite schools that had nurtured Pyle and his student N.C. Wyeth, and forward to the harsher, more brittle look of Wyeth's mature work.

The something inside the nothing

ANDREW MANGRAVITE

My God, when you really begin to see into something, a simple object, and realize the profound meaning of that thing—if you have an emotion about it, there's no end.

—Andrew Wyeth

One of the peculiar things about Modernism was its tendency to cast stones and to keep on casting them until a particular bête noir was dead. Thus it came about that artists who worked within a figurative tradition were roundly denounced as passé. They were ignored or willfully misunderstood, and so it came about that Andrew Wyeth was viewed as a realist—a camera attached to a brush stuck in front of a canvas— and no one bothered to ask such interesting questions as: Why does he paint so many empty spaces?

Here is an artist who titles a view of an empty landscape seen through an open window Love In the Afternoon. Clearly, any love going on must be occurring on the other side of that open window, right? Right— unless, of course, the painter is referring to his love of solitude and the broad "empty" landscape he presents to us.

Wyeth goes down better as you grow older. At 25, I was intensely impatient with the Sage of Chadds Ford. As far as I was concerned, the landscape was ugly, the people were plain, and that was that. Oddly enough, my feelings about Wyeth began to change when, on a whim, I purchased a second-hand copy of the book of his ”Helga” pictures. There are two ways to view the Helga paintings—they are either a classy collection of nudies, or they’re about something else. Technique, perhaps? Yes, Wyeth used a variety of techniques to obtain different effects. But there’s more to the Helga paintings. You look at them and you want to know more—more about subject (what's going on in her mind?), more about the artist (what is he thinking? What is he trying to say?).

Wyeth was the scion of a great tradition in book illustration. The achievements of Howard Pyle and his own father, N.C. Wyeth, were always before him. But what does a really good book illustration do? (Hint: it doesn't necessary describe the events in the text.) Great illustrations raise questions in your mind; they force you to look deeper, to read more into the words.

The uncanny effect of an empty room

I think that I've grown up enough to understand what Wyeth is getting at. It's taken me 30 years, but I can understand now the uncanny effect an empty room can exert. Widow's Walk, where the upper-story windows of the house look like eyes, still strikes me as Wyeth sojourning in Edward-Hopper-Land (he goes there sometimes). But Renfield—in which we see the interior of the same structure— becomes magical. Even the title—Wyeth named the work after Count Dracula's fly- and spider-eating servant— becomes evocative of isolation and strangeness, but with a hint of black humor—there must be lots of flies and spiders up there for Renfield to munch on. But then it turns serious again: Renfield eats the spiders and flies to absorb their souls. Is Wyeth referring perhaps to the souls of the generations of dead widows who must have walked up there? Have they been swallowed up in this empty space?

Interestingly, the Art Museum’s current exhibition offers two "making of" series in which we see the way Wyeth's ultimate vision emerges. He sets out to depict his old fisherman pal Walt Anderson inside his cottage. But as Wyeth continues to restate the idea, Anderson retreats into the background and finally comes to be represented by nothing more than his empty boots. In Sea Boots, the final version of the work, the empty boots stand in the sand with Anderson's house visible in the background. Mere words don't do the image justice. Anderson's house is reduced to its peaked roof looming above the gray sands like a pyramid. Anderson's boots appear to stand in a desert, and the resultant image is both grandiose and homely. It's like a salute to Beau Geste and The Four Feathers. (Remember— this is N.C. Wyeth's boy.)

The series revolving around the creation of Groundhog Day tells a similar tale. What began as a depiction of Anna Kuerner sitting in her kitchen becomes, in a final incarnation, an image of a sun-washed empty room. Shades of Renfield!

Clearly, then, Renfield is not unique in Wyeth's oeuvre. He also painted The Witching Hour and Two If By Sea, and in each case it can be said that he makes "something out of nothing.” But the truth is that Wyeth actually sees the something that abides within the nothing. In short, Wyeth is an American mystic, although I think this term would probably make him uncomfortable. Yet as his own words at the head of this essay attest, Wyeth recognizes that "there's no end" once you realize the meaning of a thing. It's interesting that as America went on a binge of materialism, we pigeonholed this unique personality as a simple recorder of everyday life. As a people, we forgot how to see. Fortunately for us, there are always the Wyeths among who remember, and as Wyeth himself has said: "If a painting is good, it's mostly memory."

A short tour of the Art Museum show

"Andrew Wyeth: Memory and Magic" is a fairly extensive show, so I'll endeavor to take you on my own short tour of it.

As you enter, you are confronted by Trodden Weed, a tempera on panel in which we see a pair of sturdy boots and a hint of a dark coat caught in mid-stride. It seems almost whimsical—like one of those family snapshots where Uncle Ernie cuts people off at the knees. The painting means much more to Wyeth, who points out that the feet (they are his own) are heedlessly trampling down the weed, which for its weedness is still a living thing. Wyeth is talking about man's heedlessness in the face of Nature. But even if you don't know that, even if you don't know that this curious work is something of a self-portrait, it still seems like a typical production from Wyeth the Sage. But then you turn a corner and find yourself confronted by…

Breakup (1994). Say whaa? This is Andrew Wyeth? What are we to make of those blackened claw-like hands impossibly thrusting out of an ice floe? Clearly, there's more to Wyeth than "photographic realism." This little work should put you on your guard against underestimating this artist.

The Lobsterman (1937) is an early Wyeth watercolor that looks amazingly like a Winslow Homer watercolor. Wyeth visited Homer's Prout's Neck studio in Maine, and he clearly didn't go there as a tourist.

Adrift (1982) depicts Walt Anderson, Wyeth’s old Maine friend, asleep in a drifting rowboat. It does suggest (1) death and (2) a Viking funeral—which, as it happens, is exactly what the artist wanted us to take away from the image. Now, some folks may feel that an artist who possesses "the common touch" is common—but I'll still take Adrift over a stack of abstract paintings.

Wind from the Sea (1947). The wind billowing window curtains is always an evocative image. Edward Hopper did something similar in his etching Evening Wind, and even John Huston used it for mood in a scene from his film The Maltese Falcon. But Wyeth saw his billowing curtains as representing the feminine presence of Christina Olsen. I suspect that Hopper just liked the starkness of the scene.

Quaker Ladies (1956). Is Wyeth a "poetic" observer of Nature, à la Ruisdael, or is there something more? Is this what he feels, or what his mind reads into it?

The eerie quality of silent snow

First Snow (Study for Groundhog Day, 1959). Call me an idiot, but I prefer the study to the finished work. Wyeth captures absolutely and for all time the eerie quality of silence that accompanies a fresh snowfall.

Public Sale (1943). This is certainly a crowd-pleasing work of realism, but consider for a moment how the painting's Cinemascope format influences our perception of it. The vertiginously-tilted point-of-view— it could almost be the view enjoyed by one of Wyeth's soaring ravens— and wide focus suggests another, cosmic drama taking place beyond this gathering of farmers to purchase a dead neighbor's belongings. Consider the importance of the season. Of course it's parochial, Symbolism 101, to link winter with death— but would it have worked as well in the summer? Clearly, the neighbor could have died as easily in July as in January. And unless Wyeth set out to create a visually exact memorial of what occurred that day, he could as easily have set his work in the summer as in winter. But as the finished work stands, the starkness of the landscape, the restricted palette of colors, the expanses of sky and land all work together to create a powerful statement on the theme of the vanity of all human endeavors.

Soaring (1942-50). It took Wyeth eight years to create this large tempera painting of ravens in flight, and it's quite an image. It's as accessible as a Disney cartoon and as strange as the very notion of flight. You can get dizzy if you stare at this one long enough.

Take a closer look

Winter (1946). This is the signature image for the show, and it's a good choice because, like Renfield, it puts you through changes. First impression: nice, homey Americana, a country boy racing through a field. But look closer: The mood is grim rather than carefree. The colors are somber. The boy seems distressed. Look closer: The "boy" could be anywhere from 12 to 40. He could well be a man. He could even be Wyeth himself. In fact, Winter arose out of Wyeth's sense of aloneness in the wake of the shocking death of his father. He was not a happy artist at the time, and Winter is not the happy, carefree image it may first appear to be.

Christmas Morning (1944). Here we see Wyeth working in an unfamiliar "surrealist" mode. Think back to Breakup, which almost opens the show. Wyeth is not Sergeant Friday of Dragnet ("Just the fact, ma'am."). But he's not Salvador Dali either, and he works best with a light touch. Christmas Morning seems too obviously poetic to me to succeed as poetry. But the painting proves the extent to which surrealism was in the artistic air in the 1940s.

Faraway (1952). This is a famous image; and the boy— Wyeth's son Jamie, sitting hunched in a field wearing his spiffy Davy Crockett coonskin cap— is an archetypal image of a child's imagination at work.

Buildings have personalities, too

River Cove (1958). The "message" of this large tempera painting is lost on city boys like me. Wyeth wants us to see those delicate tracks left in the sand by a passing heron. But the beauty is all too transient, and the rising tide will erase the bird's tracks. Wyeth himself has gone on record thusly: "Nature is not lyrical and nice. Behind the peace is violence."

Brown Swiss (1957) Another Cinemascope composition. This time Wyeth creates an interesting mood by pushing the Kuerner farmhouse to the extreme left of the painting— almost as though it were attempting to evade our glances— thus accenting the land's brown expanse. Wyeth believes that buildings have personalities of their own—something that only a real estate developer would dispute— and the Kuerner house seems to be fighting just to hang on. The painting is named for the type of cow that Kuerner kept in the empty pasture.

Finally, I also want to call your attention to a wonderful pair of nature painting that date from early in Wyeth's career. Winter Fields (1942) and Blackberry Picker (1943) are works of their time— dark, romantic, looking back on the 19th-Century Hudson Valley and Pre-Raphaelite schools that had nurtured Pyle and his student N.C. Wyeth, and forward to the harsher, more brittle look of Wyeth's mature work.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.