Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Conscience at work

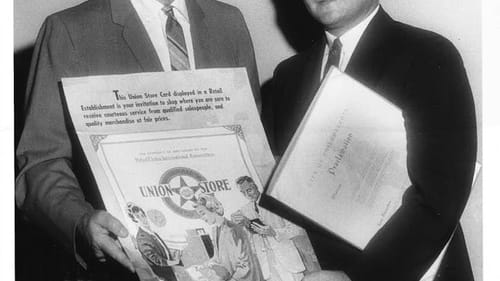

‘A Life in Philadelphia Labor and Politics,’ by Wendell W. Young III

Wendell Young (1938-2013) challenged every union-chief stereotype, as we discover in a new book, The Memoirs of Wendell W. Young III, A Life in Philadelphia Labor and Politics. When he assumed leadership of Philadelphia’s Retail Clerks Union in 1962 at age 24, he was a college graduate from Mayfair whose progressive views would warm Elizabeth Warren’s heart. For the next 40 years, he questioned authority, followed his conscience, built alliances, irritated the powerful, and advocated for the powerless.

Young’s posthumous memoir explores how things got done here in the second half of the 20th century. The book grew from conversations between Young and Francis Ryan, of Rutgers University’s Labor and Employment Relations program, over the last four years of Young’s life. Ryan edited the newly published book.

Refusing to stay out of sight

Coming from a large Catholic family in Northeast Philadelphia, Young began working part-time as a teenager in the local Acme market. When a union representative visited the store, the manager instructed part-timers to stay out of sight so they wouldn’t have to join the union. The manager said it was to save them paying dues.

When Young told his father, who’d once lost a job for participating in a union drive, the elder Young said his son shouldn’t be intimidated by people in power. The next day, Wendell joined the Retail Clerks Local 1357 (later the United Food and Commercial Workers, Local 1776). Within eight years, he was one of the nation’s youngest labor leaders.

Democrats, the Church, and civil rights

Though Northeast Philadelphia was very white and very Republican at the time, Young’s family were liberal Democrats, a distinction he used to his advantage. Before he was 21, the baby-faced Young became the Democratic committeeman for the 35th ward, knocking on doors that had never been approached by a Democrat.

Though an observant Catholic, Young did not hesitate to criticize Archbishop John Krol for living in luxury while paying archdiocesan high-school teachers very low wages. Ultimately, Philadelphia teachers established the first Catholic high-school union in the nation.

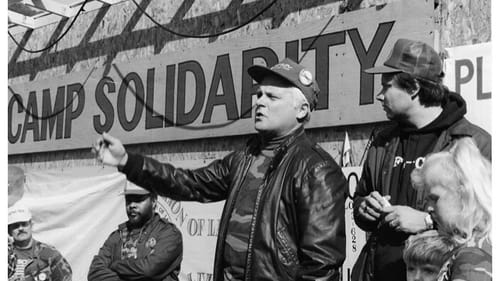

In the 1960s and ‘70s, unlike much of established labor, Young was an early supporter of civil rights, women’s rights, and the antiwar effort. “Wendell makes clear,” Ryan writes, “that in this period, really two labor movements existed in Philadelphia… [Rifts] had always divided industrial from craft unionists along lines of strategy and culture, [but] these tensions intensified in the 1970s as previously unorganized sections of the working class joined the city’s trade unions.”

The ones who couldn’t choose

Young’s positions were driven by ethics, but also by the fact that the Retail Clerks consisted of women, people of color, and part-time workers—groups not usually represented by unions. He knew that “nobody chooses to become a retail clerk as a profession; most come into it out of circumstances,” so he was determined to fight for his members. Young was effective for them, improving wages, benefits, and working conditions; expanding membership; encouraging the development of new unions; and devising creative responses to the rising threats of industrial retrenchment and global trade.

“One thing I had in common with most of the other labor leaders,” Young said, “was an understanding of the ways formal politics had a hand in shaping the kinds of gains we could make for our members.”

Young’s political support was not automatic. It grew out of a commitment to social justice, developed in his upbringing and reinforced by his Jesuit education at St. Joseph’s College, which he said “urged us not to accept things the way they were, but to ask questions, to challenge things, and to try to make life better for people.”

He thought unions should encourage “a true social democracy where everyone had security, decent wages, and equality and opportunity… for all people, not just our members.”

Principled opposition

Young’s principled positions could frustrate even political allies. At the 1968 Democratic Convention in Chicago, he enraged Philadelphia mayor James Tate when he supported the antiwar candidate Eugene McCarthy instead of Hubert Humphrey, the Philadelphia delegation’s choice.

In grocery stores, Young forced management to respect his members through vigilant adherence to contracts, persistent negotiation, and job actions when necessary. When he observed that job classifications with differing pay scales kept African Americans and women in lower-paid positions, he negotiated a single pay scale to increase wages and open opportunities.

People-to-people

In labor and politics, Young preferred conducting business face-to-face. In 1967, traveling in Brazil with a group fostering union development, Young detoured from the carefully managed itinerary. He ventured into impoverished favelas to meet the people living there and encountered poverty far worse than anything he’d seen before. Later he would say, “These Third World conditions I witnessed were the direct result of American policy, which supported corporations and permitted maximum profits to be taken from the country.”

What Young saw in South America caused him to question American intervention in Southeast Asia and he became a strong opponent of the Vietnam War, a stance that earned him the label “Communist” from conservative colleagues.

Ryan provides key historical detail for Young’s wide-ranging and engaging recollections, providing context for readers who didn’t experience these years. For those who did, the memoir offers new perspective on the plight of working people as cities shrank, employers vanished or were absorbed by conglomerates, and competition expanded globally. The book describes how similar and interdependent the inner workings of labor and politics were in the period through the eyes of a man who saw the connections and cultivated them to benefit workers.

What, When, Where

The Memoirs of Wendell W. Young III: A Life in Philadelphia Labor and Politics. By Wendell W. Young III, edited by Francis Ryan. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2019. 296 pages, hardback, $34.95. Click here.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.