Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Ties that bind and break

The Resident Ensemble Players present August Wilson’s ‘Fences’

When it comes to the playwright August Wilson, seeing his work once is never enough. Even twice can leave you hungry for more. I certainly felt that way after this spring’s fine productions of Gem of the Ocean and How I Learned What I Learned at the Arden. Luckily, the University of Delaware’s Resident Ensemble Players (REP) closes its season with a strong production of the Pulitzer Prize–winning Fences that captures all the glory and anguish so central to Wilson’s worldview.

Many Fences

The 1987 play stands among Wilson’s most famous and frequently produced dramas—in the past decade alone, it’s been on Broadway with Denzel Washington and Viola Davis (who repeated their roles in a 2016 film adaptation), and in our region at both the Arden and People’s Light. Chronologically the sixth entry in the playwright’s massive Century Cycle, it explores the reality of racism and segregation through generational and family struggles, without much of the supernatural and mystic elements that occupied Wilson’s mind in more speculative plays like Gem or Joe Turner’s Come and Gone.

But just because it trades in realism doesn’t mean it lacks the poetry that distinguishes Wilson’s authorial voice. The dialogue alternately crackles with veracity and swells to arias of near-operatic excess. Director Cameron Knight effortlessly communicates that duality, as the everyday existence of life in 1950s Pittsburgh gives way to conversations—some might even say confrontations—with God that largely go unanswered.

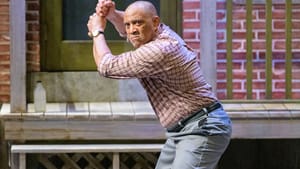

Wilson set Fences at a time when a younger generation of Black Americans saw a path to the end of segregation while older people remained somewhat skeptical. Those viewpoints come through in the relationship between Troy Maxson (Hassan El-Amin), a Negro League baseball star turned garbageman, and his son Cory (Darius Jordan Lee), a promising high-school football player. Troy’s inability to break into the major leagues embittered him—this was before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier—and they breed down to his tense relationship with Cory, who alternately wants to please his father and to build a separate identity for himself.

Family dynamics

El-Amin and Lee project a strong family dynamic, rife with complex emotions and no small amount of unspoken affection. But each actor goes beyond that central bond to create deeply moving character studies that stand on their own. Wilson presents Troy as vain, brash, self-serving, and ultimately self-destructive—all elements that El-Amin depicts effortlessly. Yet he also realizes that Troy should be seductive, so he tempers his portrayal with a strong dose of charm that goes a long way. The audience can feel it, and it helps to understand why his long-suffering wife Rose (Lisa Strum) tolerates his flights of fancy.

More than any actor I’ve previously seen, Lee presents a Cory who is unafraid to stand up to his bullying father, assert his individuality, and signal that the future won’t always look like the past. His climactic confrontation with Troy emerges as the end of an era, with son usurping father and all the psychological pain that kind of role reversal can carry. It feels utterly immediate here.

Precise performances

As he often did, Wilson infuses the supporting structure of his drama with characterful roles, all acted with precision by the REP ensemble. Will Cobbs makes a smooth impression as Troy’s older son Lyons, a small-time con man in a silk shirt (costumes by Andrea Barrier), and Jeorge Bennett Watson brings noble bearing to Jim Bono, Troy’s kindly colleague on the garbage truck.

The part of Gabriel, Troy’s developmentally delayed younger brother, is Wilson’s only concession to the mystical realm in this play—the name is no accident, nor is the fact he carries a trumpet with him wherever he goes. Often his asides stick out against the prevailing tone of naturalism, and not in a positive way, but Knight and actor Jerome Preston Bates manage to integrate the character in a way that doesn’t distract from the proceedings.

Rose has always been the question mark in the equation—at least to me. She remains passive throughout much of the play, largely coming into her own in the wake of a betrayal. Luckily, Strum’s finely calibrated performance imbues the woman with an undeniable inner strength that lets her stand up to Troy in her own quiet way. And once the dam breaks in the second act, there is no turning back. Combined with Lee’s forceful work, mother and son feel more like partners in progress than ever here.

More Wilson

Wilson’s title has literal and metaphorical meaning—we build fences to protect ourselves, our family, our property, but we also erect barriers to our feelings and emotions. In doing so, we run the risk of fencing ourselves into identities that leave us standing alone. That simple revelation comes across with subtle, unadorned poignancy in REP’s production.

Fences appears more often than most Wilson plays, but often it's not as good as it is staged here. (That includes a superb physical production, with true-to-life sets by Stefanie Hansen and moody lighting from Eileen Smitheimer). Even if you feel you’ve had your fill of Wilson this season, take the opportunity to bask in his world and his words once more. You won’t regret it.

What, When, Where

Fences. By August Wilson, directed by Cameron Knight. Through May 12, 2019, at the Thompson Theatre, Roselle Center for the Arts, 110 Orchard Road, Newark, Delaware. (302) 831-2204 or rep.udel.edu.

The Roselle Center for the Arts is an ADA-compliant venue. To learn more about accessibility or request accommodations, call the box office or email [email protected] at least five days prior to your desired performance. Accessible parking spots are available on every floor of the venue’s adjacent parking structure.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Cameron Kelsall

Cameron Kelsall