Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Moving parts

The Annenberg Center Live and NextMove Dance present Dance Heginbotham

Dance Heginbotham (DH), a company founded in 2011 and based in New York, recently made its Philadelphia debut at the Annenberg. Its namesake, artistic director and choreographer John Heginbotham, has an impressive background, including dancing with Mark Morris Dance Group for 14 years, receiving a Guggenheim Fellowship, and collaborating with musicians from Joshua Bell to Shara Nova. DH’s mission is equally impressive: to move people through dance. The company attempted to achieve this through a program of two very different pieces.

The differences between Twin (2012) and Easy Win (2015) had the potential to be a strength. They reflected opposition in style, movement, music, and theme, with the former’s stark, mechanical elements countering the latter’s emotion and musicality. In a sense, both dances engaged with the concept of control. Twin suggested the tension between human and machine, like several other works I have seen in the last few years. This issue is topical, even prescient, as technology becomes increasingly enmeshed in human life. If we can’t survive without it and robots take our jobs, who is master and who is servant? On the other hand, Easy Win—a dance dedicated to the choreographer’s mother in honor of her 70th birthday—celebrates how passion and music can temporarily possess human bodies and sometimes bring them to joy.

Bodies and machines

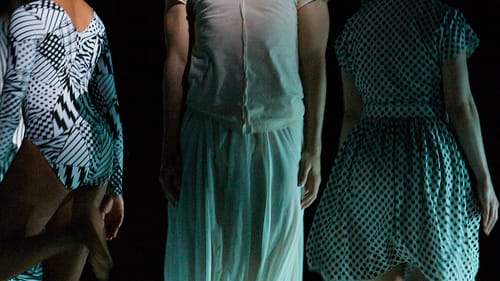

The evening began with Twin’s exploration of the meeting places between the biological and the artificial. Five dancers, in costumes by Maile Okamura in variations on black and white, gathered together and stood still until one placed a hand atop another’s head and spun it to set the group in motion.

John Eirich, Lindsey Jones, Courtney Lopes, Victor Lozano, and Macy Sullivan pranced, cartwheeled, and jerked their arms like automatons to lively electronic music by Aphex Twin. Heginbotham’s creative use of space and tempo enlivened many sequences. The dancers formed two lines across the stage, then shifted into another formation.

The strongest section, a duet comprised of Jones and Lopes, began with the two mimicking a cat clock’s side-to-side eye and tongue movements, their mouths open wide. The dancers’ strength and flawless execution supported Twin’s themes of machines and control. They leapt to their feet from prone positions like battery-powered toys suddenly switched on. Black-and-white geometrical patterns on the long-sleeved leotards they wore bolstered a mechanical image. This duet ended with Jones and Lopes looking like figures from the world inside the computer in the movie Tron (1982), thanks to lighting designer Nicole Pearce’s creative use of pink illumination.

But other segments of Twin were slower and less interesting, such as a solo for Eirich. Wearing a white skirt, he made frustrating progress across the stage, moving a few feet, then crawling or rolling back. I was perplexed by a later sequence in which the five dancers pointed overhead while a sixth, Kristen Foote, stood motionless at the back of the stage. Foote’s odd appearance made more sense when the piece ended, the dancers took their bows, and I could see that she wore a walking cast on one leg. A playbill insert with casting updates had removed her name from the list of Twin’s dancers, probably because of an injury.

Potential to move

Following intermission, Easy Win took the program in another direction. It was performed to live music from pianist Ethan Iverson onstage. Okamura’s costumes, in shades of gray with washed-out orange and yellow accents, offset the stark color scheme of Twin. The mixture of athletic tights, cropped tops, and short, tulle-like skirts also looked more like practice than performance attire, evoking an easier, more natural quality than Twin’s aesthetic of artificial rigidity.

Once again, variations in tempo, level, and synchronicity were the highlights of Heginbotham’s choreography. The opening scene blended synchronous with asynchronous movement. One energetic sequence drew on ballet. I admired arabesques in which dancers turned, creating new shapes, and a series of exuberant barrel turns. Piano notes seemed to send dancers’ legs into high kicks.

Easy Win also dragged in places, including a slower portion performed in red light. But it transitioned into a section that resembled an animated social dance. Dancers formed pairs, and Eirich and Jones performed an elegant lift. Later, pairs looked more like lovers as they rolled across the stage in embraces that formed, broke apart, and reunited.

Easy Win portrayed movement spurred by music and feeling rather than a power cord, forming an interesting counterpoint to Twin. But both works only hinted at images and themes, leaving the audience wondering what they meant to communicate. As a result, DH’s Philadelphia premiere did not move me, but it did leave me inspired by dance’s potential to move, especially when performed by such talented dancers.

What, When, Where

The Philadelphia debut of Dance Heginbotham. Choreography by John Heginbotham, presented by Annenberg Center Live and NextMove Dance. March 15 and 16, 2019, at the Annenberg’s Harold Prince Theater, 3680 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. (215) 422-4580 or annenbergcenter.org.

The Annenberg Center accommodates the needs of individuals with physical disabilities. Find details on accessibility here. The Annenberg has a gender-neutral restroom.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Melissa Strong

Melissa Strong