Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Women's work

PMA's Another Way of Telling: Women Photographers from the Collection

Do women see differently from men? And what happens when they look through a viewfinder? The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s (PMA) Another Way of Telling: Women Photographers from the Collection considers the question.

Seeing and knowing

One thing is certain: Were it not for Dorothy Norman’s vision, PMA’s photographic collection would not have taken shape as quickly or as impressively as it has.

Philadelphia native Norman (1905-1997), a writer, social activist, arts patron, and accomplished photographer in her own right, was mentored by, and a benefactor of, Alfred Stieglitz, with whom she worked closely in the 1930s and ‘40s. Norman collected photography before the medium was commonly recognized as art, and in 1968 her gift of more than 1,500 photographs to PMA formed the collection’s core in one stroke. Another Way of Telling contains works from Norman’s gift as well as other works from the collection and new acquisitions.

Norman wrote the first full-length biography of Stieglitz and took some of the last images of the legendary photographer. Six small prints are on view depicting Stieglitz and his gallery, An American Place, which Norman helped fund and run. The spare compositions, typical of Norman’s style, imply rather than depict the subject: A pair of gnarled hands (Alfred Stieglitz, Hands, Variant IV); a candlestick telephone before a framed portrait (An American Place, Telephone and Alfred Stieglitz Equivalent); and an empty gallery painted with sunlight and shadow (Walls, An American Place, New York).

Revelations on both sides of the lens

Many works on view are head-and-shoulder portraits of female subjects, which begs the question of why women photographers would portray other women so predictably. The answer is obvious: to show the women behind the faces.

Those behind the lens are revealed as well. In Anne Brigman’s Self-Portrait with Mask (1922), she holds a mask at her shoulder, as though removing it. She turns her face to the side with a curious smile and closes her eyes. Perhaps hiding what she’s thinking?

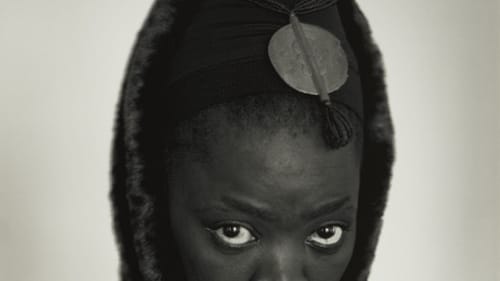

While traveling, Zanele Muholi made impromptu self-portraits, using whatever lighting and props were at hand. In Ntombi II (Hail, the Dark Lioness, 2014), Muholi inclines her head but peers into the camera with upturned eyes, her gaze probing, challenging.

Stella Simon’s Chinese Coat (c. 1920-31) depicts a woman in a beaded coat – but, unlike fashion photography, this picture is all about the person wearing the garment. She is a series of undulating curves – oval face; neck bending over to a round shoulder; arms, hands, and fingers twining around her torso like graceful vines. Simon’s treatment remains relevant a century later, when women in photographs are frequently used as props for whatever is being sold. In Another Way of Telling, women are not props. There are no vacant stares, no forced smiles. On both sides of the lens, women are perfectly at ease and in control.

The camera as power

Made in the time of Rosie the Riveter, Maya Deren’s portrait Carol Janeway (1945) is subversively assertive. Viewed from a distance, Janeway appears to be a mid-20th-century housewife, blond hair pulled back at the nape of her neck, hands on hips, standing before a wall hung with items one would assume are kitchen implements, including two strainers. Closer inspection, however, reveals an axe, a saw, a hammer, and a half-hidden six-shooter. Wonder what the strainers are for?

Hannah Price’s camera is her weapon. As a newcomer to Philadelphia and unaccustomed to the catcalls from men as she walked around town, Price turned the tables. She photographed those who violated her privacy and dignity, producing a series that includes Walking from CVS, West Philly (2010), a portrait of a confused young catcaller astride his bicycle. You can’t help but smile.

Making art, viewing the world

From the early 20th century, the acceptance of photography as an activity for women played off the prevailing stereotypes – women were attentive to detail, had an instinct for beauty, and could put nervous subjects at ease.

Technological advances, such as the development of smaller cameras and celluloid film to replace heavy glass plates, made it easy for women to take and develop pictures. Photography became an accessible creative outlet and, by 1910, 20 percent of U.S. photographers were female. Whether hobbyists or serious artists, they used photography to record and interpret their worlds.

Some illustrated stories from literature, the Bible, and their own imaginations. Julia Margaret Cameron’s Call and Follow, Let Me Die (1867), was inspired by a poem written by her neighbor, Alfred Lord Tennyson. Anne Brigman’s Stardust (1913), a gauzy depiction of a youth in nature that echoes Impressionism, could illustrate a children’s storybook.

Other women recorded the world around them. Before marrying fellow photographer Paul Strand, Hazel Kingsbury Strand documented postwar relief efforts in France for the Red Cross. Dorothea Lange’s Cable Car, San Francisco (1956) captures time and place in a knee-level shot framing just a corner of the tram and a female passenger’s demurely crossed legs.

Perhaps the initial dismissal of photography as art is precisely what enabled women to gain a foothold and excel. Making the most of the path available, women put personal, professional, and creative aspirations on film, extending and elevating the photographic form.

What, When, Where

Another Way of Telling: Women Photographers from the Collection. Through July 16, 2017, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art's Perelman Building, 2525 Pennsylvania Avenue, Philadelphia. (215) 763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.