Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A Wyeth centenary brings out important figures

Brandywine River Museum of Art presents 'Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect'

To celebrate the 100th anniversary of Andrew Wyeth’s birth (1917–2009), the Brandywine River Museum — repository of Wyeth family works and lore — has upped its regional-icon status by mounting the major exhibition Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect.

Taking another look

For some, the Brandywine River Valley is a vacation destination. To others, it’s a scenic day trip. For Andrew Wyeth, it was both home and inspiration.

Beginning with the strong early-1930s watercolors that sold out New York’s famous Macbeth Gallery in two days, the chronological survey (co-curated by Audrey Lewis of the Brandywine and Patricia Junker of the Seattle Art Museum) hits his artistic highlights, but also showcases seldom-seen works from private or family collections.

Wyeth, beloved of audiences and collectors but lambasted by some midcentury art critics, is often viewed as a realistic painter. But the exhibition’s impressive scholarly catalog — jointly published by both museums and Yale University Press — explores the broader and deeper art historical and analytical landscape. That depth is readily apparent when you swap out a “quick-picture walk-by” type of visit and dedicate time to these works.

Putting Wyeth back where he belongs

Wyeth’s supposed “realism” is actually a rich brew of symbolism, narrative painting, and magic realism, often underpinned with the abstraction he was accused of fleeing. The hills, trees, and tiny rills that are his hallmark are (of course) about so much more. But seeing this exhibition opens another window: He loved to paint people. Andrew Wyeth is a monumental and masterful portraitist.

Of the more than 100 works on view, 54 are figural. Some are studies, some are fully realized portraits, but half depict figures, faces, personae. This tally doesn’t include his representations of animals or those works in which there is a significant human force present by inference or made vivid by absence. (Missing here is the famous Christina’s World, which hangs in a busy hallway in New York’s Museum of Modern Art and was not released for this exhibition. Its less-than-stellar location is often considered by arts mavens to be a big-city curatorial snub.)

The artist’s figural focus is unsurprising when you consider his training and artistic DNA. Andrew was the youngest child of powerhouse early-20th-century illustrator N.C. Wyeth, who himself was trained by that powerhouse master of illustration Howard Pyle. Both men painted vibrant, revealing works that were also character studies of heroes and villains in the books they wrote or illustrated.

At 15, Andrew entered his father’s studio to begin formal art studies, and his first assignments focused on the human skeleton and figural drawing. This retrospective is filled with vibrant portraiture from those early days, the first of which is a 1936 pencil sketch of his father that effortlessly captures N.C.’s power and determination.

An independent spirit

Some portraits are watercolor, which the artist used to explore freedom and movement. Some are drybrush, where most of the water is removed from the brush, requiring the artist to manipulate layers of dry pigment. Many are works in tempera, a demanding, precise medium for which Wyeth became well known. Tempera is tricky; it dries quickly and demands speed as well as pinpoint accuracy.

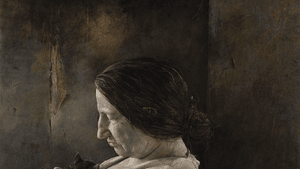

Karl (1948), a telling portrait of Wyeth’s Chadds Ford neighbor Karl Kuerner, is an interior-looking profile with a private and slightly suspicious gaze that might be mistaken for the artist himself. Miss Olson (the famous Christina of that iconic Maine painting) offers an unstinting look at the hardscrabble woman, moved to tenderness as she holds a kitten. And British at Brandywine (1962), one of the most interesting figural renderings, contains an ironically whimsical depiction of toy soldiers sitting in a sunny farmhouse window that looks onto the fields where their real-life counterparts fought and died for independence.

Andrew Wyeth sought — and achieved — independence his whole life. But he was also strongly connected both to the landscapes and people where he lived. In spite of the reticence of his national artistic profile, Wyeth loved to look at and into people in the same way he dissected landscapes. In addition to the catalog, a slim volume that accompanies the exhibition — Andrew Wyeth: People and Places — offers a thoughtful guide into this part of the artist’s life. It contains family photos, an introduction by museum director Thomas Padon, and an essay by Karen Baumgartner, senior researcher of Wyeth’s catalogue raisonné.

Yes, you can see the Brandywine Valley in Wyeth’s magical realist paintings. But you can also see the landscape in the faces of those ineluctable Wyeth people.

In mid-September, Andrew Wyeth: In Retrospect goes to the Seattle Art Museum, after which most of these works will return to the private or family collections from whence they’ve come.

What, When, Where

Andrew Wyeth in Retrospect. Through September 17, 2017, at the Brandywine River Museum of Art, 1 Hoffmans Mill Road, Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania. (610) 388-2700 or brandywine.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Gail Obenreder

Gail Obenreder