Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Racial awareness vs. colorblind casting

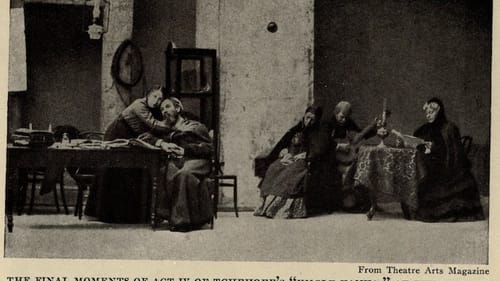

Quintessence Theatre Group's 'Uncle Vanya' and the hybrid classic

Since the inception of drama in ancient Greece, the best plays do not make statements. Instead, they leave the audience with a series of questions on the universal challenges of being human. The United States of America remains divided — and culture has become the front line in these debates. But as democracy is the twin sibling of drama, so too must the theater be a place where we all come together as a community to explore complex questions and cultivate our collective humanity.

The "American quilt"

In his 44-year life at the end of the 19th century, Anton Chekhov wrote four of the world’s greatest plays. His interest was in humankind’s awkwardness, boredom, and innate fallibility. Chekhov insisted that “realism” had no place in theater, nothing could be superfluous, and there was never a barrier between what transpired onstage and the audience. The Russian literati’s inability to pin down Chekhov’s beliefs or intent earned him many negative reviews. It is also why we are still staging his plays today.

I grew up in the Mount Airy section of Philadelphia in the 1980s. During that time in U.S. theater, the classics (specifically Shakespeare) were at the forefront of diversity casting, an opportunity left woefully underexplored in most contemporary U.S. drama at the time. The classics avoided the “realism” of television and championed “colorblind” casting, a term generally applied to the practice of casting actors in plays without regard to race.

Since its founding, Quintessence has strived to reflect the diversity of Philadelphia in our productions. But over the last eight years, my perception of race, gender, and my own privilege has shifted. And while I believe the best actor for a role should get the part, any exercise that asks an audience to ignore race or make race “invisible” in 2017 is inherently problematic for me.

{photo_2}

The American quilt is a pattern of many colors and fabrics. If we hold a mirror up to nature (a gauntlet Shakespeare threw down 400 years ago), we cannot create theater for Philadelphia if our acting ensembles are 80 percent white and performing in a city whose population is 55 percent people of color.

Authenticity and truth

A series of obstacles hamper the goals of inclusive casting for a classical theater in Philadelphia. First, 75 percent of professional actors in Philadelphia are white. Second, we live in the age of “authenticity.” When “authentic” becomes synonymous with “truth” in theater (where an actor must literally be what the character is), the transcendent power of the actor and the audience’s theatrical imagination becomes strangled by realistic representation; theater suffers.

At Quintessence, we are exploring how to conscientiously consider race as part of adapting the classics to contemporary U.S. life. Last summer, I emailed Steven Wright and asked him to play Vanya. If you don’t know Steven Wright, you do not know one of Philadelphia’s best actors. I have seen Steven perform standup comedy, naturalism, Shakespeare, and children’s theater. Wright can make you think, laugh, and cry all at the same time. To me, that is the essence of the Chekhovian actor.

We first met to discuss the project at a coffee shop, and said I wanted the production to embrace the fact that he was African American. We talked through the implications of this choice and, like the process of translating Russian to U.S. English, we felt the added national resonance of race would only enhance this Russian classic for our audience. Once Steve was on board, I felt it was essential that the actors playing his mother and his niece be African-American women.

Segregating our stories

In recent years, I have engaged in many conversations about systemic racism in U.S. institutions (theatrical, educational, political, economic). This process was an opportunity to continue to explore and ask vital questions. In the play’s third act, Uncle Vanya finally stands up to Serebryakov, a celebrated professor and Vanya's brother-in-law. (In this production, the professor is played by Dan Kern.) Vanya has spent his adult life working to support and sustain Serebryakov, and suddenly realizes his idol will never fulfill his promise as one of Russia’s great thinkers. Vanya’s life has been wasted, and he insists on the recognition of his sacrifices and the work he has done to sustain his family and its dreams. He declares Serebryakov a fraud and his worst enemy.

One of the many questions Chekhov’s play asks is why it is okay for one man to spend his life in a sheltered and privileged existence (in this case academia) while others labor and suffer to sustain the economy in which this privilege exists.

As a country, many of our citizens are experiencing epiphanies like Vanya’s, questioning why they have worked for an American dream that will never come true. By casting Steven Wright and Jessica M. Johnson (with Rosalyn Jamal and Daniel Ison supporting them), this production not only tells Chekhov’s story but asks why we remain complacent in the systemic subjugation of our black brothers and sisters.

I believe we (with the assistance of Annie Baker’s incisive translation) have created a powerful, funny, awkward, truthful, and timely American Uncle Vanya. I wish we could have engaged more of Philadelphia’s 1.5 million citizens with our production, or that the Philadelphia Inquirer had deemed seeing one of Philadelphia’s sons, Steven Wright, playing Vanya worthy of press coverage. Without audiences and critics willing to recognize difference while also cherishing what unites us, we will continue to segregate our stories, our artists, and our audiences.

Uncle Vanya ends at the close of a long, hot summer. As we disappear into the darkness of night, the word “gone” rings out, dirgelike, into eternity. The play’s final words are a promise from Sonya, our young and once hopeful heroine. Sonya begs Vanya to believe that when they die, they will at last find rest. She says “We’ll rest” six times. In Russian, Chekhov’s wrote my otdokhnyom, which roughly translates to “we shall breathe easily.” Without changing Chekhov’s intent or Baker’s adaptation, we understand that many Americans feel this lack of air, particularly those within the African-American community. I believe it is our collective challenge and responsibility to combat this suffocation and to ensure that we all find the breath we need before we die.

To read Mark Cofta's review of Quintessence's Uncle Vanya, click here.

What, When, Where

Uncle Vanya. By Anton Chekhov, adapted by Annie Baker, Alexander Burns directed. Quintessence Theatre Group. Through June 18, 2017, at the Sedgwick Theater, 7317 Germantown Avenue, Philadelphia. (215) 987-4450 or quintessencetheatre.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Alexander Burns

Alexander Burns