Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

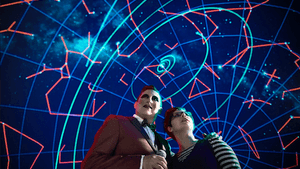

University of the Arts/FringeArts co-production asks, "Why live?"

Philly Fringe 2016: César Alvarez's 'The Elementary Spacetime Show'

“Haven’t you ever been faced with a feeling of void?”

It’s an early line in César Alvarez’s FringeArts Curated world premiere, The Elementary Spacetime Show. It’s simple, but it captures two major and seldom-acknowledged truths of suicidal thoughts.

Those who haven’t experienced depression or other associated mood disorders, addictions, or mental illnesses may gain new understanding from Alvarez’s protagonist, Alameda, a teenage girl who attempts suicide in the musical’s opening scene. The feelings that lead someone to consider, attempt, or complete suicide aren’t always abject misery or sadness.

These are part of the story, but in my experience, suicidal thoughts hinge much more on a state beyond the pain: An inability to imagine what comes next. It’s the absence of the normal sensations of a purpose and a future. It’s like trying to propel your thoughts into next week, next month, or next year, and seeing nothing but blankness.

It’s also notable that Alameda doesn’t just sing about being in the blankness. Instead, she asks that very matter-of-fact question. The lyrics make it seem as if anyone who doesn’t know what she’s talking about is in the minority. It frames her experience as both common and wrenching, a tough truth for something as frightening and stigmatized as suicide.

An urgent topic for teen girls (and everyone else)

Alameda awakens in a “liminal space” (not purgatory, but an “anteroom to the void”). She must win a surreal game show to gain the right to choose a return to her life, or a departure to “the great big black butthole of the universe.” And Alameda is easy to relate to, not a cautionary tale about a mentally ill other.

The Elementary Spacetime Show is timely. According to statistics from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention (AFSP) — which has tips for recognizing risk factors for suicide and getting help — suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, claiming about 42,773 Americans per year. The foundation notes the number is probably higher, with underreporting likely.

That number means an average of 117 suicides per day. There are also an estimated 25 attempts for each completed suicide; the problem goes deeper than the lives lost. In 2014, men accounted for seven out of 10 suicides. Thus, men are four times more likely to die by suicide, but women actually attempt suicide three times as often as men do.

A 2016 NPR story notes that over a near-30-year span (with stark suicide increases in every age group except people over 75), suicide among adolescent girls increased the most. Girls between ages 10 and 14 still make up a small number of overall U.S. suicides, but between 1986 and 2014, suicides in this population tripled over 15 years, from .5 to 1.7 per 100,000 people, also faster than any other group.

“Every time”

As Alvarez’s lyrics make clear, Alameda’s sojourn is never framed as an isolated event. The game unfolds “every time a teenager tries to commit suicide.” Its spangled, raucous, sympathetic host is even weary of the musical numbers, and there are many all-in-a-day’s-work clues from the ensemble and staging that remind us Alameda’s story isn’t unusual, much as we’d like to believe that the risk factors for suicide won’t touch us or our loved ones.

In Alameda’s voice, the show captures a parade of real-life sentiments associated with depression and suicidal thoughts, including a helpless sense of division in oneself. “I don’t want to feel like this,” she sings. “I want to want to live.”

Alameda is also convinced that everyone who loves her would be better off without her. As many depression patients will understand, she says, “on Earth I’m too thin-skinned — everything seems to hurt me more than it hurts everyone else.”

Staging the problem

In its guidelines for journalists reporting on suicide, AFSP urges the media to downplay “big or sensationalistic headlines,” or “prominent placement” of information about methods or locations of suicide. Without proper context, these can worsen the risk, and lead to more suicides.

So it’s fair to ask whether the conspicuous, explicit nature and setting of Alameda’s suicide attempt — not to mention an entire two-hours-plus performance packed with song and dance numbers questioning the value of existence — is a problematic way to present the issue.

Ultimately, the show weaves an odd kind of empathy that is as brash and flamboyant as it is deadpan, and as fatalistic as it is optimistic. For all its sensationalism and stirring harmony, it doesn’t varnish the painful truth of Alameda’s predicament: the history of neglect, substance abuse, and misery that makes her want to cease existing, and what probably awaits her if she goes back to the land of the living. She might wake up institutionalized with a tube in her stomach, handcuffed to the bed.

But Alameda’s creativity, intellect, and determination — even after performing the ultimate act of despair — shine in a story with no easy or obvious solutions. In a totally unconventional tale about the imagined aftermath of suicide, Alvarez finds the truths of mental illness.

What, When, Where

The Elementary Spacetime Show. Through Sept. 24, 2016 at the Arts Bank at the University of the Arts, 601 S. Broad St., Philadelphia. (215) 413-1318 or fringearts.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Alaina Johns

Alaina Johns