Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Guess who's coming to the resurrection?

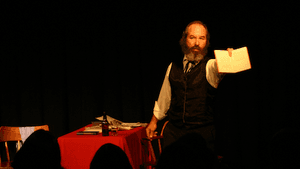

InterAct and Iron Age Theatre present Howard Zinn's 'Marx in Soho'

You don’t expect a full house for a limited engagement, one-person show at 4pm on a Saturday, especially when the subject is a 19th-century political economist and the author is a historian on busman’s holiday as a playwright. But that’s what InterAct Theatre Company, in this co-production with Iron Age Theatre, saw for its staging of Howard Zinn’s Marx in Soho.

What was the draw? Two words: Karl Marx.

Come-to-Jesus moment

Marx has been dead for a long time, literally and figuratively. His economics and political science were taught as gospel in Communist countries before the fall of the Soviet Union, or at least the ghastly distortions of them known as Leninism and Stalinism. In the West, they were merely a heresy to refute, if they bore mentioning at all. Nowadays, at universities, Marx is remembered mostly by a few tenured radicals on life support. Who, then, has resuscitated him for a popular theater audience?

Two words again: Donald Trump.

You knew something was brewing in the election cycle, when millions of voters were not only willing to support a presidential candidate who defined himself openly as a socialist, but also to crowdfund his campaign. Instead, we got The Donald, who in his first full week in office brought a goodly number of citizens into the streets in outrage and disbelief. Some, I suspect, also spilled into InterAct. They weren’t looking for a political alternative so much as a moral symbol, a figure incorruptible, uncompromising, and (perhaps for that reason) quasi-mythical.

About midway through Marx in Soho, Marx (Robert Weick), visiting earth on a brief furlough from the beyond, says that, yes, he knows Jesus there. He looks straight out at the audience and says, “He isn’t coming back.” There was laughter at this. A few lines later, he adds that he has come instead.

Nobody laughed.

Man of the moment

So it is that, against all odds, Karl Marx appears to be a man for our moment. In a country that seems destined to be run by Goldman Sachs executives, Marx is the supreme anticapitalist, the man who’ll have no truck with the enemy. People who’ve never read him, to whom he is hardly a name or even a rumor, know that much about him. And for anyone who wanted to hear the message, Zinn’s hagiographic account (updated to reflect recent events) delivers it loud and clear. If there was any doubt about it being preached, moreover, the spare set (uncredited) featured a winding staircase leading up to a platform, as in a pulpit, which Weick climbed at strategic moments of fire and brimstone.

This wouldn’t make for theater, of course, or not for long, were there no gentler contrasts. Zinn, best known for A People’s History of the United States, a bottom-up look at the long-popular struggle to realize the ideals of American justice, wants us to see Marx, warts and all—or, in this case, boils, from which he suffered painfully.

We see him in his domestic roles as husband, father, and neighbor, being tender and sometimes defensive about his complex and often tense marriage, loving toward his brilliant daughter Eleanor, sorrowful about other offspring lost in childhood, and rueful about missing life’s pleasures in a decidedly Victorian heaven. We see him, too, fighting rude but charismatic anarchist Mikhail Bakunin, his chief rival for supremacy in the 19th-century socialist movement. At one point he rebukes Bakunin for drunkenly urinating out a window. Bakunin believed in spontaneous mass action and dismissed the notion of a revolutionary party as a formula for dictatorship. The subsequent careers of Lenin, Stalin, and Mao showed him to have a point, but Zinn touches on this only passingly. Similarly, he shows Marx exulting over the short-lived Paris Commune of 1871 as a model for true socialism, while ignoring his initial response to it as a strategic mistake.

Then and there meets here and now

A play isn’t a seminar, though, and Zinn’s larger purpose is to humanize Marx while presenting him as a renewed figure for our times—the guy who, for all his own unforced errors and the 20th-century tyrannies that governed in his name, essentially got it right in calling out modern capitalism as inhumane and destructive. In dramatic terms, he’s only partially successful; historical Marx was a far more forceful and commanding figure than presented here, and no doubt an often less likable one. Weick's performance was engaging, nuanced, and powerful when needed, but it lacked the spark of a world-historical figure.

Still, that wasn’t really the point of the performance. For once, audience was more important than play, and what its reaction and presence had to say was that the country is badly in need of focused, impassioned, and unyielding moral vision.

Say what you will about the guy, you get all that in Karl Marx.

[Editor's note: Please see box for additional dates and times during the 2017 Philadelphia Fringe Festival]

What, When, Where

Marx in Soho. By Howard Zinn. John Doyle directed. InterAct Theatre Company. January 28-29, 2017, at the Drake, 302 S. Hicks Street, Philadelphia. (215) 568-8079 or interacttheatre.org.

Also running at the Philadelphia Fringe Festival. September 7 to 22, 2017, Philadelphia Ethical Society, 1906 S. Rittenhouse Square, Philadelphia. Tickets available at FringeArts, 140 N. Columbus Boulevard, Philadelphia, (215) 413-1318, or fringearts.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller