Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

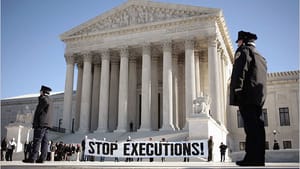

The Nine Lives of Capital Punishment

Evan Mandery’s 'A Wild Justice'

There is a growing consensus that capital punishment is on its way out in the United States, the only developed country in the western world that retains it. In the past six years, six states have abolished it. The number of capital sentences and executions has steadily fallen, and in 2013 were at their lowest levels in many years.

Against this backdrop, Evan J. Mandery’s book A Wild Justice: The Death and Resurrection of Capital Punishment in America appears as a cautionary tale. In the 1960s, as abolition was being enacted across a broad spectrum of western countries, the U.S. appeared to be headed in the same direction. After 1967, a de facto moratorium was in effect, and no person would be executed in America over the next ten years. There had been no rush to abolition by the states nor had the Supreme Court ever cast doubt on the constitutionality of capital punishment. A slow accretion of state cases, however, appeared to be undermining both its rationale and its practice. In 1971, the Supreme Court agreed to hear a number of test cases, including Furman v. Georgia. It certified in its grant of certiorari a single question framed by abolitionists over the preceding decade: “Does the imposition and carrying out of the death penalty in this case constitute cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments?”

There was no particular confidence that the Court would find in the affirmative in Furman, let alone make a broad ruling on its question, for along with the rest of the country it had taken a rightward turn following the election of Richard Nixon as president in 1968 and the installation of a conservative Chief Justice, Warren Burger. When the Court issued its 5-4 decision in June 1972, however, it shocked observers across the board by striking down every capital statute in the country. By a stroke of the pen, the death penalty had ceased to exist in America.

Abolitionists believed they had won. Their euphoria was short-lived. Not only was the Court narrowly divided, but there was no consensus about the basis of its ruling: Each justice issued a separate opinion. The gravamen of the decision, then, was not that capital punishment was unconstitutional per se, but that existing statutes were flawed and defective. If the statutes could be rewritten to satisfy the Court’s new requirements, the death penalty could come back.

It did, with a vengeance. It was one thing to allow the death penalty to expire quietly, or to drive a stake through its heart by clearly declaring it to be unconstitutional under evolving standards of decency, in Oliver Wendell Holmes’s famous phrase. Instead, the Court had stuck a finger in the eye of each of the 31 state legislatures with a capital statute. The backlash was almost instantaneous. Within four years, not only had each of these states passed a new statute, but four other states had joined them. The question was whether these statutes met the Furman test. If even one did, it could serve as a model for all the rest.

The case that brought the death penalty back to life was Gregg v. Georgia (1976), which upheld the new Georgia statute. This time the vote wasn’t close, 7-2, with only the core abolitionist justices, William Brennan and Thurgood Marshall, dissenting. Marshall read his dissent from the bench, a highly unusual practice. Brennan declared that the death penalty was a species of “official murder.” Both men agreed that it denied fundamental human dignity.

Brennan and Marshall remained in the Court’s minority, and their views still do. Ironically, three members of the Gregg majority — Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell, and John Paul Stevens — would eventually come to reject capital punishment entirely. Had their ultimate views matured earlier, as Mandery points out, Gregg might have cinched Furman and marked the true end of the death penalty. Instead, in Mandery’s phrase, it “resurrected” it. The result, to date, has been a further 1,359 executions.

In retrospect, however, Gregg’s actual outcome was a foregone conclusion, given the climate in the country. The state legislatures’ rush to enact the new capital statutes, and the opinion polls that consistently backed them, showed that standards of decency had not evolved as Brennan and Marshall might have wished. Marshall addressed this point by suggesting that public sentiment was uninformed and should not therefore be regarded as “conclusive.” Alas, the public is often uninformed, but in a democracy its opinion is indeed deemed to be conclusive.

Is this the beginning of the end?

The tide that now appears to be running against capital punishment must thus be viewed with great caution. The public may not be so much averse to it as frustrated by the agonizingly slow pace of executions. An untoward event — say, another major terrorist attack — could lead to a demand to streamline the legal procedures that currently hobble it. This would doubtless result in the execution of more factually innocent persons. A sufficiently aroused public, however, could find this an acceptable price. In any case, a future Supreme Court, remembering the outcome of Furman, is likely to tread very warily in these waters. And states that abolish the death penalty today might want it back tomorrow, even without a judicial poke in the eye. It’s happened before.

I think, as Brennan and Marshall did, that capital punishment is the ultimate affront to human dignity. I think it is not only equivalent to the offense it seeks to punish, but far worse. It may be the single worst thing a society can do to its members. For that very reason, however, abolitionists should be very circumspect in hailing what may prove yet another false dawn. The death penalty is deeply rooted in the most atavistic impulses of civilization, and, as opinion polls have shown, countries that have abolished it are not immune to its continuing lure. Even after nine lives, its career may not be done.

What, When, Where

A Wild Justice: The Death and Resurrection of Capital Punishment in America by Evan J. Mandery. W. W. Norton, 2013, $29.95. http://books.wwnorton.com/books/978-0-393-34896-5/

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller