Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

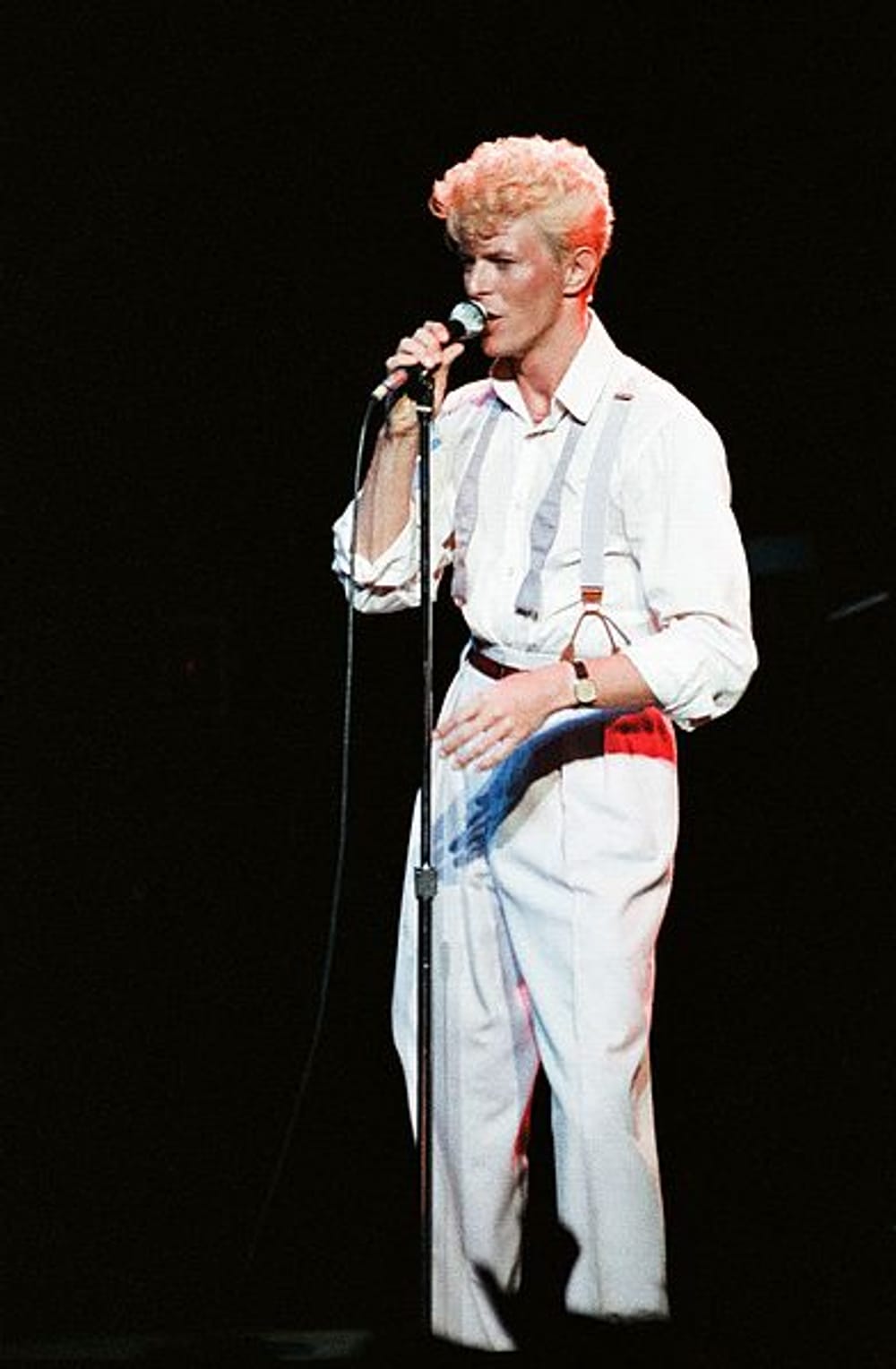

Three things I learned from David Bowie

Long ago, I got over being embarrassed by growing up on pop music. There’s no moral fiber in this accomplishment; it happened at about the same time the classical world got over the fact that composers were growing up on pop music. Then I was liberated by the realization that no one was excessively interested in what I got over or didn’t get over. So it was all good.

I like pop as far as it goes, which isn’t considerably far, normally, but it is fun, and sometimes what you want is fun. But some songs make me go ooh when they enter the room, and they still do. Only recently did I discern the reason; it’s so simple, I don’t know why I didn’t figure it out before. I even wrote about it here and still didn’t connect the dots.

The pop songs that send me have strong downbeats. That’s it. The ne plus ultra of rock is backbeat, but in these tunes backbeat is either absent or is balanced by an aggressive downbeat. It can show up in any pop style, so, something as countrified shuffle as “In the Summertime” by Mungo Jerry (1970) is, in my mind, brother to the funk/swing-band stew of David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” (1983). Well, I was all grown up by 1983, come to think of it, but oh, do I like “Let’s Dance.”

1. Serious moonlight

It happens only once in a long while (except for Paul Simon; with him it’s all the time): a high heater lyric missiles by your head and makes you duck. When you recover, you ask: Where did that come from? “Let’s sway under the moonlight, this serious moonlight” is a fastball at your head. Moonlight is many things to poets, but I don’t ever recall it being described as serious. Bowie liked it so much that he named his Let’s Dance album tour not the Let’s Dance Tour but the Serious Moonlight Tour.

The lyrics jolt beyond moon/June pop rhymes, and the music sweeps past its genre, too. This rock tune is strongly colored with blues (Stevie Ray Vaughan on the baying, reticent lead guitar), funk (the slamming downbeat), and swing (saxes that stutter and echo).

When composing, I look for words that make me duck. And then I try to write music that zigs when it should zag or use red when the words ask for blue.

2. Put on your red shoes and dance the blues

This is another great line, which Bowie declaims all wrong the final time he sings it, which makes it even better. “Put on your red shoes and dance the blues” is how he turns it, emphasizing almost all the wrong syllables. Put is a downbeat, a command, not an invitation. Your is higher than the other words, punching that up a notch. (In working something out, I’m always viewing the lay of the line, seeing what’s higher or lower or louder or softer — because that’s where the emphasis is, whether I realized it when I wrote it or not.)

Your interests me. Not "Put on red shoes" but "You know those shoes, the ones you already have? Yes, put those on." Red, an adjective, gets a strong beat. Everything in this sentence is emphasized except the noun: shoes.

But then, the most egregious wrong. Weak words should fall on weak beats, and the conjunction and is among the weakest of words. But and is on the strongest beat — the downbeat — welded in a double anvil-blow with dance, which makes it even stronger. The entire line’s biggest emphasis is and.

Capital-F funk is what that is in pop, but where else do we see this? Colonial hymns. Nineteenth-century Sacred Harp tunes. The Charles Wesley hymn “And Can it Be that I Should Gain?”: 18th-century words, 19th-century music. Lutheran chorales are knotted through and through with accented eins and unds.

I love “Let’s Dance” all the more because of that and.

Dancing the blues with red shoes, of course, casts against type. Red shoes are glamorous, come-hither, but the blues are the blues, man. You could dance the blues — if you had to — slow, head down, sliding more than stepping. But red shoes scream for attention, and the last thing you want when you have the blues is attention.

You want to be left alone, but the whole point of “Let’s Dance” is that the song walks over to you, sitting there in your doldrums. It stops in front of you, holds a hand out to you, and says,

3. Let’s dance

Good music invites you to dance with it. The composer asks, “Come with me.” It’s Don Giovanni to Zerlina: Andiamo. Who asks, must lead, and when the music’s good, we don’t wait until we’re ready or wallow in our despair. We just get up and follow.

Backbeat? Why not? Downbeat? You bet. Red shoes? Yes. Swing, funk, blues? Yes, yes, yes. And we follow the music, no matter what. "If you say run, I’ll run with you; if you say hide, we’ll hide." That is some serious moonlight.

Good music doesn’t whine that nobody listens to it. Good music doesn’t blame audiences or musicians or marketing or anybody else. Good music doesn’t blame at all. Good music takes charge. It grabs you out of your chair, says, “Let’s dance,” and before you know it, you’re dancing.

And that is what I learned from growing up on pop music — and long ago, I got over being embarrassed by it.

Editor's note: This essay was originally posted on May 6, 2014; we are bringing it out of the archives following Bowie's death on January 10, 2016.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Kile Smith

Kile Smith