Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

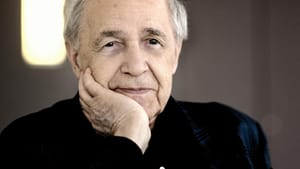

Boulez est mort

Pierre Boulez: An appreciation

When Pierre Boulez was selected to succeed Leonard Bernstein as the music director of the New York Philharmonic in 1971, the choice seemed, superficially, quite harmonious. Both men were composers and educators with vibrant personalities who were committed to expanding the audience for classical music. But a mere prick beneath the surface revealed a wide chasm of aesthetics and temperament between the two. In many ways, Boulez was the anti-Bernstein.

Boulez, who died on January 5th at the age of 90, was always ahead of his time. His tenure in New York was brief and rocky. He broke with many traditions, including chamber music on his programs, arranging pre-talk lectures with composers, and inviting audiences to hear concerts while seated on blankets — he generally strove to expand the traditional notion of what a symphony concert should look like and sound like. Sound familiar? Yes, those are some of the very practices orchestras around the world are using to entice new listeners.

He was a brilliant conductor, with a famously keen ear for the slightest variation in pitch. His podium style was in sharp contrast to the flamboyant Bernstein; he conducted sans baton, and his feet rarely left the ground. The New York critics at the time declared him to be cerebral, even “scientific,” whatever that meant. But his many recordings, absent the visual cues, reveal an honest and passionate artist with an incredible sensitivity to color and texture, and a disciplined feel for pacing that rendered large works by Mahler and Stravinsky with a complete architectural wholeness.

Joyful imagination

The music-loving public may recall Boulez as a conductor, but this was really his day job. His greatest legacy will surely be as a composer, not just one who created remarkably thoughtful work, but as an inspiring leader for a generation of composers and musical thinkers, constantly pushing the art forward with a joyful sense of imagination.

Boulez joyful? It was not the image that was put forth by the music media, and Boulez himself took no great pains to correct his perceived persona as haughty and even angry. His career sprang out of the wasteland of post-World War II Europe, when Schoenberg’s 12-tone technique, which had gone almost completely dormant, was seized upon by the young lions, with Boulez leading the charge. He infamously declared, in 1952, that “any musician who has not experienced — I do not say understood, but truly experienced — the necessity of dodecaphonic music is useless.”

That comment both revolted and frightened many of that time, and in retrospect, it has a callow ring. The late Hans Werner Henze, a great contemporary of Boulez, was driven away from purest dodecaphonic composition by this kind of rhetoric, which reminded him of the very fascism that he had just survived. But I have always relished the gleeful courage of Boulez, his delight in the new, his call to push boundaries outward as a kind of artistic imperative.

Serialism beyond harmony

His own music reflected this philosophy. In yet another bit of youthful flame-throwing, again in 1952, he declared that “Schoenberg est mort,” but I think it is reasonable to accept this as a literal statement (Schoenberg had, in fact, died a year earlier). Surely his implication was that the art of music lives even as individual innovators pass away. His work is deeply indebted to Schoenberg, even as he took the serial technique beyond just harmony, and into the realms of rhythm and form as well.

The simple truism is that all composers wish to be appreciated and write with an individualistic vision of beauty. Boulez had a reputation for creating works that are intentionally difficult (notoriously, his Second Piano Sonata) and indifferent to the appreciation of the listener. This is nonsense. Boulez explored new technical parameters, but always at the service of the expression of beauty. His most celebrated work, "Le marteau sans maître (The hammer without a master)" is certainly complex, but also overtly sensual. It both honors Schoenberg and falls into a Gallic tradition for delicate texture and subtle emotional expression, in the manner of his teacher, Messiaen, but also referencing Debussy, especially in the infusion of Asian musical influences.

Luminosity and integrity

Boulez could be a polarizing figure, but for those who fell into his sphere, he was uniquely inspirational, heroic, even. As a performer, he sought the highest possible artistic standards, revealing the standard repertoire and the music of living composers with luminosity and integrity. As a composer and intellectual leader, he espoused and practiced an esthetic that questioned everything, while simultaneously subsuming the wisdom of all that came before. His life’s work is a model that is sorely in need today, and he will be deeply missed.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.