Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

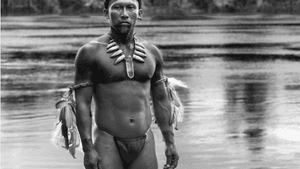

Colonized and colonizers meet in the pre-WWII Amazon

Ciro Guerra's film 'Embrace of the Serpent'

In 1926, the German physicist and future Nobel laureate Werner Heisenberg — later to play an equivocal role in Hitler’s attempt to build an atomic bomb — put forward his Uncertainty Principle, which almost immediately became a postulate of modern physics. Heisenberg’s principle, a sophisticated version of the Evil Eye, stipulated that the mere act of observation alters its object, so that all description is at best approximate and all knowledge is therefore inexact.

If observing subatomic particles in a cloud chamber makes them wriggle, ethnography is a far more ethically challenging enterprise. The student of what used to be called “savage” or “primitive” peoples may try to take the greatest care, but his or her mere presence is inherently destabilizing. The proverbial tribesman who flinches from a camera is operating on sound instinct; what he does not know is that there is no getting away from it, and that the harm has been done whether the shutter clicks at that moment or not.

Embrace of the Serpent, Colombian filmmaker Ciro Guerra’s extraordinary third film, is about such encounters and their disastrous results. It is based very loosely on the diaries of two ethnographers, Theo Koch-Grünberg and Richard Evans Schultes, who investigated the Amazon region in 1909 and 1940, respectively, both in the company of the same guide, an indigenous shaman named Karamakate. Schultes seeks, among other things, evidence of his predecessor’s fate (he survived his journey and lived until 1924). Like Kurtz of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, both men also seek something else in the Amazonian wilderness: themselves.

The best of a bad lot

Jan Bijvoet’s Theo is a mysteriously ailing middle-aged man, sick from the jungle, but sicker within. Although the winding Amazon still seems pristine, it has already been invaded, not by scholars but by Western traders and fortune-hunters who seek to exploit its resources and its indigenous population. Theo is accompanied by Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), a local who wears Western clothing and has been educated as a guide. Manduca sees in Theo the best of a bad lot. Theo is at least willing to recognize humanity in his people, and thus, may be their only hope for survival. His temporizing is met with contempt by a young shaman, Karamakate (Nilbio Torres), who sees him as a traitor to his race, and the white men, for all their destructive rapacity, as fools in a land they can never understand and which will ultimately swallow them. But Karamakate, despite his repugnance, enlists in Theo’s quest in hopes of finding the remnants of his tribe and saving what remains of a sacramental culture.

The film’s first half follows these protagonists and their tense, mutually suspicious relationships. Theo believes that his ailment can be cured by yakruna, a rare medicinal hallucinogen attached to the rubber tree and prized by Western interests. Karamakate agrees to lead him to it in return for help in locating his tribe. Their voyage reveals the devastation European predators have left in their wake, and the folly of all concerned — for Theo, in his doomed search for health and well-being; for Manduca, in his illusion that the white man can be induced to spare his people; for Karamakate, who hopes that he is not alone. In the climactic episode of their journey, they come upon a Catholic mission, inhabited by a crazed monk and the native children he terrorizes. Theo’s attempt to intervene leads to disaster, underscoring the impossibility of any interaction between conquerors and conquered but mutual corruption and destruction.

The film’s second half is necessarily anticlimactic. Richard (Brionne Davis), like Theo, is fixated on yakruna, which with the coming of World War II has military utility. His only hope of tracing Theo lies in engaging the elderly Karamakate (Antonio Bolivar), now resigned to his solitude as the last of an extinct tribe. There is an encounter, parallel to that of the monk and his mission, with a white man “gone native” who has set himself up as the god of a local tribe, its own culture now in ruins. The evocation of Heart of Darkness (and its film adaptation, Apocalypse Now) is clearest here: nothing remains to express such degradation except horror.

Guerra’s film, then, aims to compress the long, genocidal history of the Americas into the story of a treasure hunt that loses its way in a trackless wilderness. Yet the film’s real protagonist is the Amazon itself, the winding serpent of the Americas that, anacondalike, will have the body and spirit of everyone who intrudes on it. Karamakate is the only man who can live on terms with it, but his wisdom will die with him. The film is clearly an elegy for him, and a brutal dirge for the American indigenes slaughtered by their colonizers. But its most emblematic scene has nothing to do with humans: it depicts the devouring of a forest snake by an aquatic serpent under the impassive eyes of a jaguar who observes it. This is the river and its jungle, where life feeds on life, and death is the price of profusion. It is a price that humans are not exempt from paying, and the refusal of it — the mindless destruction of modern Amazonia in the name of clearance and development — brings only death without life.

What, When, Where

Embrace of the Serpent. Ciro Guerra directed. Philadelphia area showtimes.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller