Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Where the Jewish gentry came to shvitz

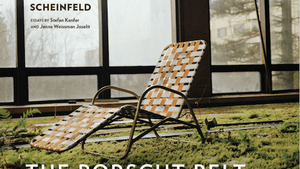

The Gershman Y presents The Borscht Belt, by Marisa Scheinfeld

In the beginning, Marisa Scheinfeld wanted to call her project “Leftover Borscht.”

But a five-year odyssey to document the ruins of the former Jewish vacationland known as the “Borscht Belt” became less an exercise in irony and more a deep dive into themes of death, renewal, memory and change.

A very special homecoming

Scheinfeld, 35, was raised in the Borscht Belt — or rather, what was left of it by the time she was a child. The region, formerly home to 500 hotels and thousands of bungalow colonies, had been a thriving summertime refuge for Jews formerly shunned from “restricted” vacation spots.

By the time Scheinfeld’s family moved upstate from Brooklyn in 1986, just a few of the iconic hotels — Kutsher’s, the Concord — remained. She remembers sauntering past desk clerks with her grandfather, a well-known card shark, to swim in luxe pools, play shuffleboard, and listen to older folks’ stories of the area in its heyday.

But it wasn’t until Scheinfeld was a photography graduate student in California casting about for a thesis project, that a professor advised her, “Shoot what you know.“

"I knew that my hometown had this tremendous past. I knew that past was slipping away. I started to go to as many as I could find: bungalow colonies, hotels, resorts, to photograph them in all four seasons, not move or manipulate anything, in the conditions in which they were left.”

Beautiful ruins

With equal parts patience and chutzpah, armed with a Pentax 645 and Kodak color film, Scheinfeld examined what remained — once-grand hotel entrances now bearded in weeds; a dining room repurposed by local teens into a paintball arena; a swimming pool-turned-marsh, with broken chaise longues crumpled by its side.

“I knew that I would likely find ruins,” Scheinfeld says. “But I couldn’t have imagined the magic and sublime scenes that I found…what a pool looks like in winter or in spring when plants start to grow through the floor. The colors, the textures.”

Eventually, Scheinfeld made 129 photographs, enough to fill a book, The Borscht Belt: Revisiting the Remains of America’s Jewish Vacationland, due out in October. Eighteen of the photographs, along with an array of Borscht Belt memorabilia, are on exhibit at the Gershman Y.

They are arresting, absorbing images: a soap dish in a hotel bathroom, nearly unrecognizable in its deterioration, with moss crawling over the ceramic shelf; a guest room at the Tamarack Lodge, where a salmon-colored dial phone rests on a bare mattress, handset detached as if the caller stepped out mid-conversation and never returned.

Not a single person appears in any of the pictures, yet the images hold echoes of the camaraderie that once was: a dining room at The Pines, round wooden tables upended and splotched with paint; a line of green counter stools from Grossinger’s coffee shop, their once-shiny bases freckled with rust, the padded seats cracked and gray.

Life goes on

And yet, the pictures teem with life, the insistence of nature and the reclamations of time. In a 2011 photograph of the lakefront promenade at the Laurels Country Club, the steely water is home to a queue of ducks. Wildflowers and weeds sprout from what was once a patio at The Pines. Through the window of a guest room at Grossinger’s — reduced to crumbling walls and a fire extinguisher — the viewer can glimpse a bird hovering, mid-flight, in a bouquet of foliage that is coral, chartreuse, and forest green.

At first, Scheinfeld thought she was composing a photographic elegy. “But really, once I really started to consider it more and more, it’s really a commentary on the cycle of life, the metaphor that everything has a birth and a death and all that space in between.”

What happened to unravel the Borscht Belt’s appeal? There’s a royal flush of reasons: affordable air travel that put further-flung vacation spots within reach, assimilation that lessened the need for a Jewish-identified refuge, shifting demographics, changing tastes.

Scheinfeld’s large-scale prints, color saturated and detail rich, remind us that what felt like an era — a few mid-20th-century decades of stand-up comedy in the ballroom and rumba lessons on the south lawn — was really a blip. What’s constant is change.

“If you look at the Catskills in the 1800s, there was this whole movement of painters and writers and musicians who would come up here,” says Scheinfeld. In recent years, Orthodox Jews from New York have begun to vacation in the area; there are proposals to turn some sites into large-scale casinos. “I think it will continue to be a destination. I don’t think it will ever be what it was.”

Memorabilia in two vitrines underscore that theme of transience: a key to the Concord and a small, paper-wrapped bar of Nevele Country Club deodorant soap. There’s also a cluster of plastic picture viewers, souvenirs guests would buy at the end of a festive evening in one or another long-gone ballroom, stamp-sized memories of a night that was, already, starting to fade.

What, When, Where

The Borscht Belt: Revisiting the Remains of America's Jewish Vacationland. By Marisa Scheinfeld. Through Nov. 18, 2016 at the Gershman Y Gallery, 401 S. Broad St., Philadelphia. (215) 545-4400 or gershmany.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Anndee Hochman

Anndee Hochman