Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Habitats for imagination

The Gershman Y presents Lynne Clibanoff and Amze Emmons

You wouldn’t think noise from a hardhat zone would enhance art, but at the Gershman Gallery, it does. Ambient construction sounds, from buzzing saws to the thunk of piles being driven, are a fitting accompaniment for works by Lynne Clibanoff and Amze Emmons.

Worlds in cigar boxes

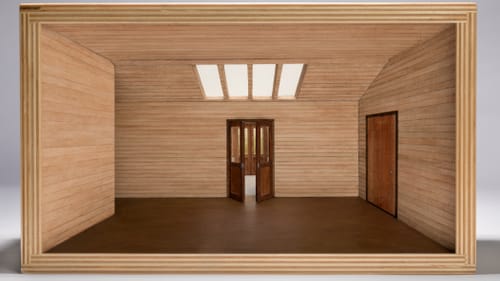

Clibanoff, a Philadelphia-based sculptor, has an architectural bent: She constructs whole worlds the size, if not the shape, of cigar boxes, from little stairwells to miniature interiors. Unfurnished and unpeopled, they are habitats for the imagination.

Places where Clibanoff has visited, traveled, or worked inspired her recent work, such as Jackie’s House, North Side (2016), a woodsy retreat with double doors opening to a glass atrium. It isn’t clear if Dormer (2015) is a model or just a wish, but I hope the all-white, divided-light window exists somewhere.

Vanishing points

The Crypt, Marino Marini Museum, Florence (2015) possesses exquisite detail and more color than many of the works here. From the entrance, dark-blue floors and light-blue walls are visible. Peering into the receding interior, we can just spy four nested doorways curving off to the right, and the core of the crypt, where the floor changes to green-and-yellow stripes. The view, mostly edges and slices, feels like looking through a keyhole.

LeWitt-Kandinsky (2017), meanwhile, feels more like peering through the wrong end of a telescope. Viewers stand at one end of an expansive gallery capped with a vaulted blue and white ceiling. This room narrows as it recedes, ending at a single square smaller than a postage stamp, a barely visible work of art. It would be nice to sip a shrinking potion and, like Alice, go exploring.

Let there be light

As if their size and the way in which the field of view recedes don’t make viewing challenging enough, the little boxes have no internal illumination. In some, Clibanoff inserted Plexiglas skylights for indirect light that changes through the day. The Gershman helpfully provides flashlights, enabling viewers to inspect nooks more fully, or to mimic shifting natural light.

Don’t take the stairs

Then there are Clibanoff’s many staircases, leading we’re not sure where (and in most cases, it’s better that way).

A Little Dark (2012) looks like the steps in every underground garage: Solid concrete treads zigzag up through subterranean depths, probably lit by a flickering fluorescent, saturated in car exhaust and the panic of drivers who forgot their level. Plan for the Future (2012) will resonate with anyone who has seen an old Twilight Zone episode. Its dizzily off-kilter treads are poised to send climbers tumbling into the abyss.

However, the stairway in Down and Out (2011) seems inviting enough. It descends to small wood-and-glass double doors and a garden beyond. There’s probably a snake waiting.

Uninhabited vs. abandoned

While Clibanoff’s worlds appear uninhabited, those of Amze Emmons seem abandoned. Debris collects in his corners, specks drift through his atmosphere, and blow along the ground in his landscapes. It looks like everyone left in a hurry.

The detritus is instantly recognizable to anyone who walks through a city, especially the area around Broad and Pine, where the Gershman sits. Emmons’s drawings lack the grime of our fair, constantly-under-construction city, but he has the details down cold. Take "The Study of Rules Governing Exceptions," a series in which 007 (2015) depicts a pothole filled with hot pink gravel, a spectacular improvement on the sticky black stuff — someone alert the Department of Streets.

Beautiful destruction

In 010 (2015), four pale-orange cones guard a sinkhole. Blue and green timbers lie across the opening and a diagonally striped, vaguely European street sign sticks up out of the hole. As in real life, no one works on this potential ankle-breaker.

Another in the series, instantly familiar if you attended college before the digital age, is 006 (2014), a campus message board. These tubular, wooden upright structures held fringed notices offering tutoring, apartment space, rides to share, textbooks for sale, typing services, and other ancient communications. After the first week of classes, they were messy eyesores. In Emmons’s idealized version, untouched notices flap neatly and rise in a perfect chromatic spectrum, of orange, gold, and yellow. At the edge of the picture, a few cotton-candy-like globs gather, perhaps escaped from a recently filled pothole.

Emmons’s Suitable for Mass Transit (2008) sets another recognizable scene: A sparkling bus canopy with colorful seats is the lone survivor in an urban battlefield. A bunker of dirt rises around it, shards of wood sticking up and lying in piles, like the remains of a neighborhood teardown. Concrete partitions — like those used to funnel traffic — obscure the view. Rubble piles everywhere. We can’t tell if this zone is under construction or demolition, but this much is clear: The buses will arrive either too early or way too late.

What, When, Where

Lynne Clibanoff/Amze Emmons. Through August 27, 2017, at the Gershman Y's Gershman Gallery, 401 S. Broad Street, Philadelphia. (215) 545-4400 or gershmany.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.