Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

The fabric of life

Philly Fringe 2016 review: Ann Hamilton's 'habitus'

Words woven together become a poem; threads, a cloth. Visual artist and MacArthur Fellow Ann Hamilton intermingles text and textile in habitus, a dual-site exhibition and installation for The Fabric Workshop and Museum (FWM).

“We’re rarely, in our lives, without the touch of cloth on our skin,” notes the National Medal of Arts recipient, known internationally for multimedia installations and performance collaborations. From swaddling us moments after birth, to shrouding us in death, cloth is as present as thought. Indeed, much thought and many words have been devoted to cloth, from fabrication methods, to dyeing and stitching, to its uses, and how it makes us feel.

Exhibition: Surveying Philadelphia textile collections

In the exhibition, on view at FWM, Hamilton draws on the history of cloth, dressing three floors in artifacts gathered from museums and collections across the region. There are blankets from Winterthur Museum, a rainbow of dyed remnants from Philadelphia University, a swatch from Marianne Moore’s jacket and the poem she wrote about it, from The Rosenbach of The Free Library of Philadelphia, Amish dolls from the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and more.

Hamilton groups textile and textual artifacts in cases, opening a conversation among items fashioned across centuries, and adds her own explorations of fabric art and the written word.

A book of 17th-century handwritten notes from The Rosenbach rests alongside Slaughter (prototype) (1997), Hamilton’s single organza glove formed from looping silvery thread that spells out a poem by Susan Stewart. It is one of three works from the ongoing collaboration between Hamilton and Stewart, a poet and professor of humanities at Princeton University. In another piece, Hamilton inscribed Stewart’s companion poems “CHANNEL” and “MIRROR” on a ribbon of cloth wound on reels that can be cranked forward and back for reading.

A physical and virtual commonplace

habitus includes several handwritten notebooks of collected wisdom about cloth across the centuries. These collections on color, stitching, spinning and more, known as “commonplaces,” consist of material gathered from disparate sources but focused on a single interest, similar to a scrapbook modern collectors might make.

In essence, the exhibition itself is a commonplace on a grand scale. In addition to items selected and created by Hamilton, the public submitted published writing referencing cloth through the microblogging site tumblr; samples of these are available for taking from authors as wide-ranging as Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (“My ornaments are fruits; my garments leaves, Woven like cloth of old, and crimson dyed”) and Milan Kundera (“By now history is nothing more than the thin thread of what is remembered stretched out over the ocean of what has been forgotten…”).

Immersion: Spinning clouds of cloth

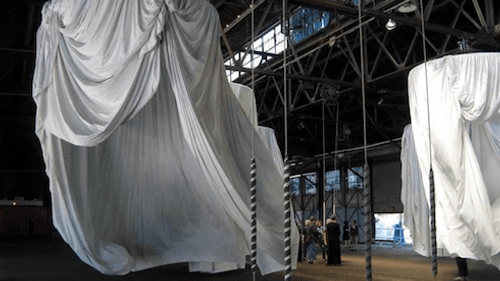

The immersion portion of habitus unfurls at Municipal Pier 9, a weathered storage space on the Philadelphia waterfront, preparation of which required considerable assistance from the Delaware Riverfront Corporation. In this massive area, Hamilton built an environment of a dozen swirling curtains of Tyvek cloth, 30 to 40 feet long and dyed what she calls the “color of atmosphere.”

The curtains hang on circular rods suspended from the shed roof, billowing in the breeze off the river. Each is attached to a pulley, which in turn is connected to two thick bell pulls that descend almost to the floor. Tugging on the ropes rotates the rods, and the curtains circulate, releasing a ghostly whine from small concertinas attached to each apparatus. The ghostly moan evokes the pier’s past, replete with sailors and stevedores.

Initially, visitors are agape at the scale of the space. Soon they step into the cloudbank of drapes, reaching for ropes or running into rotating curtains, to see what it feels like to be surrounded by the whirling, whooshing fabric. Invisible except for shins and shoes, they snap pictures, smile, and laugh.

An ideal location

This is Hamilton’s first major exhibition at FWM, though her collaboration with the institution stretches back to 1999. Philadelphia is the perfect place for an artistic consideration of cloth, as the city was a center of highly skilled textile production for more than a century. The scale of the cloth manufacturing, dyeing, and finishing trades here contributed significantly to Philadelphia’s reputation as the “workshop of the world.”

The first silk spun in the United States was produced here in 1815. Cotton and woolen worsted were made in the city, as well as hosiery and carpets. Frankford was a textile center even before it was formally part of Philadelphia, from the mid-19th century until the 1930s, known for its mills, dye works, and the blankets and calico produced in them. By 1909, more than 100,000 Philadelphians were employed in the city’s mills, more than the Massachusetts cities of Lawrence, Fall River, and Lowell combined.

In assembling habitus, Hamilton has fused Philadelphia’s text and textile traditions in new ways, forcing a reconsideration of the relationship between them, and with ourselves.

What, When, Where

habitus exhibition. Through Jan. 8, 2017 at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, 1214 Arch St., Philadelphia.

habitus installation. Through Oct. 10, 2016 at Municipal Pier 9, 121 N. Columbus Blvd., Philadelphia.

Information for both at (215) 561-8888 or fabricworkshopandmuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.