Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Peter Blume: Nature and Metamorphosis, at PAFA (second review)

The major narrative of 20th-century American art is the rise, triumph, and partial supersession of Abstract Expressionism. Its storyline is the disruption of the genteel tradition represented by such figures as John Singer Sargent by the revolutionary European art currents of the early 1900s, and the gradual evolution of a style that conquered Old Europe and marked the beginning of America’s international cultural hegemony. Europeans had just begun to get the hang of it themselves when it was dethroned by a brash successor, Pop Art, which led in turn . . . well, to nothing in particular. There has been no dominant style in the fine arts — literature and music included — for going on half a century, but instead what looks like an increasingly exhausted recycling of old repertoires.

One effect of this is to make the radical innovations of the early to mid-20th century stand out in bold, heroic relief. Those were the days! From Picasso to Pollock, giants walked the Earth, and we creep in their shadow. The relentless commercialization of our visual culture has contributed to this; Cubism, Expressionism, and whatever fits in between have become auction house (and art shop) brand names. What to do, though, when the brands stop coming?

One result of our, shall we say, cultural pause, is the investigation and reevaluation of earlier figures who don’t fit the grand narrative. Recently, three such artists have gotten a rehearing locally. Charles Burchfield’s luminous landscapes were the subject of a show at the Brandywine Art Museum; Thomas Hart Benton, once scorned as a provincialist realist, has his masterpiece, American Today, on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where it will now permanently hang; and Peter Blume, born Piotr Sorek-Sabel, a stubbornly representationalist painter throughout his long career, has had a major retrospective at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts as well as a trailer show at the New York gallery ACA, which represents his estate.

Artist forgotten and remembered

Blume was once famous, and in the 1930s and 1940s, he was a name to be reckoned with. His best-known painting, The Eternal City, once hung prominently in the Museum of Modern Art’s galleries, but it was quietly removed in 2001, and hadn’t been seen since, until now. Nor had he had a significant show since 1976, sixteen years before his death in 1992.

Amends have been made. The 56 paintings and 103 drawings on display at the Pennsylvania Academy represent a substantial portion of Blume’s output, and, with the 60-odd pieces at the ACA Galleries, they give us as complete a look at the Russian-born artist as we are likely to get. Together, the shows reveal a man who, like Benton, was thoroughly conversant with Modernist techniques without subscribing to the Modernist aesthetic.

What Blume discovered, with Chagall as a precedent, was that the human figure could not only be expressively distorted but, as in Cubism, set free in the visual field. Chagall left other objects more or less as they conventionally appear, but Blume, beginning with his first major painting, South of Scranton, juxtaposed figures and their surroundings in novel ways — in this case, sailors on holiday jumping off their ship into what appears to be the middle of a small-town street. The effect — not only of breaking up space but also narrative — was unsettling, and remains so. In some ways, Blume was developing a more fractured and sophisticated extension of Renaissance art, in which unrelated figures like donors frame the primary image or smaller incidents appear within the principal representation. Blume’s vision was more like the juxtapositions of suggestive but unrelated dream sequences. Surrealism clearly gave him pointers here — Magritte, like Miro, would remain a permanent influence — but magic realism was the effect he ultimately sought.

Theatrical harum-scarum

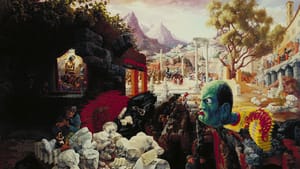

Blume’s next major painting, and his best known, was The Eternal City. Its central figure is a caricatured Mussolini whose head emerges, fiercely glaring, out of an accordionlike contraption that is part jack-in-the-box and part Chinese dragon. The image is superbly right: a theatrical harum-scarum that projects both menace and absurdity.

The Mussolini image springs out of a labyrinth of ruins, beyond which are scenes of crowds being brutalized by soldiers on a plaza, all enclosed against a vista of hills and a fading sky. Set against Mussolini is a Christ enclosed in a red-curtained display window, wearing his crown of thorns but even more mockingly adorned with touristic trinkets — an image (not specifically Christian, but, as in Chagall’s depictions of Jesus, a generic Man of Sorrows) that would recur later in a series of Blume’s works inspired by a trip to Mexico. The Eternal City thus marks a further development in Blume’s art, in which asynchronic images refer to displacements not only in space but time; in short, to history.

From there, it was only a step to the final stage of Blume’s maturation, namely, the creation of mythologies whose images expressed not merely historical but symbolic significance. This in turn responded to the civilizational collapse of World War II, and the Holocaust in particular. The transition appears clearly in The Rock, a major postwar work whose central image is a freestanding mountain peak, peeled back like a fruit and vaguely alluding to the Star of David. The peak flowers on one side, with a heap of bones on an altarlike projection on the other; this is paralleled by the scene of reconstruction that dominates the left side of the canvas and the untouched ruin on the right.  A sweep of figures cutting and working stone moves rhythmically against this, but the unmet question is whether their labors can succeed: whether, that is, the West can be put back together again.

A sweep of figures cutting and working stone moves rhythmically against this, but the unmet question is whether their labors can succeed: whether, that is, the West can be put back together again.

Rock on

Blume would explore this question in one form or another for the remainder of his life. Rock — the source of aspiration and building, as well as the image of natural presence — remained a critical but ambiguous symbol, as in Boulders of Avila, in which Blume portrays himself and his wife Ebie picnicking under an enormous natural overhang that both gives shelter and threatens collapse. But the most compulsive image for him as time went on was that of an apocalyptic deluge, as in Recollection of the Flood (1967-69); From the Metamorphosis (1979); and the series of late paintings, some left unfinished, that begin with Crashing Surf, whose slablike, partially submerged rocks, suggestive of skyscraper towers, are battered by great waves. Never less than vivid, the best of these paintings are haunting and prophetic. Always anchored by a prodigious technique and annotated by the many drawing studies — often quite remarkable works in their own right — they emerge from, they are a legacy that challenges us in a new century that has not yet settled accounts with Blume’s own.

Above right: Crashing Surf (1982, Elisabeth and William Landes, courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, © The Educational Alliance, Inc./Estate of Peter Blume/Licensed by VAGA, New York)

For Anne Fabbri’s review of the PAFA show, click here.

What, When, Where

Peter Blume: Nature and Metamorphosis, through April 5, 2015 at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, 128 North Broad Street, Philadelphia. 215-973-7600 or www.pafa.org.

Peter Blume (1906-1992) through February 14, 2015 at ACA Galleries, 529 West 20th Street, New York. 212-206-8080 or www.acagalleries.com.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Robert Zaller

Robert Zaller