Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

Alone together

Photographs by Dave Heath at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

We’re all in this together, yet each of us is alone. Dave Heath learned this harsh existential lesson far too young and has spent a career coming to terms with it through his camera.

Abandoned at four by his teenaged mother and her parents, then rejected by a foster family who accepted two children, only to decide that one was sufficient, Heath grew up in Philadelphia orphanages. Enthralled by Life magazine’s photographic storytelling, he made the camera his confidante, revealing himself completely from behind the lens.

Expressions mute, eyes speak volumes

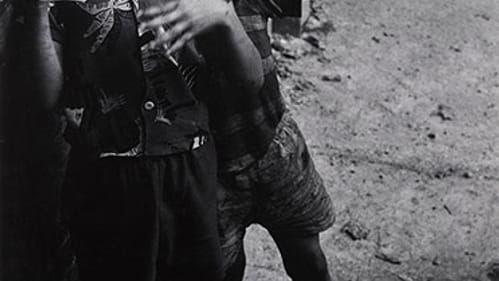

City streets were Heath’s first studio: Philadelphia; Chicago; New York, where he came to prominence; and later Toronto. Isolation is a prevailing theme: Subjects gaze cryptically into the camera, their expressions unreadable. Often they stare beyond the frame, lost in thought. Crowds of individuals populate a single location, but don’t interact; disconnected, in their own worlds.

The dispossessed and alienated are Heath’s subjects, and he wrote his autobiography with their images: children with ragged clothes and dirty faces, stone-faced or crying, hardly ever smiling. A sweet-faced girl with tangled hair and huge light eyes stares out from the cover of Heath’s masterwork A Dialogue with Solitude, as if to say, “Here I am,” and nothing more. In New York City (1962), a small boy backs up against a car fender, face frozen in a howl of tears, and a woman stands nearby, oblivious. Is he injured? Anticipating punishment? Is she his mother? We don’t know. In another photo, two boys stand in an alley, perhaps playing? Then you notice that one has his arm poised over the other, ready to deliver a blow.

Revealing the private face

Heath, who had to find his way alone, photographed passengers looking out of car windows and riding in elevated trains, going who knows where? Many photos are of just one person, and even the group shots set one occupant apart. Faces are expressionless, but their eyes are full of sorrow, uncertainty, loneliness, fear. We recognize that look: the one we all have when our public mask falls away and our faces betray the thoughts that wake us in the middle of the night. We see it in a mirror and are caught off guard. Who is that? Then, recognizing ourselves, we shake it off and look away. But in these intimate portraits, our gaze lingers.

Philadelphia stories

The work that carried Heath from a Philadelphia orphanage to two Guggenheim Fellowships is presented in Multitude, Solitude: The Photographs of Dave Heath at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Organized by the Nelson-Atkins Museum in Kansas City, Missouri, the exhibition covers the 81-year-old artist’s work in the 1950s and ‘60s, a period that culminated in A Dialogue with Solitude, the exhibit and book that brought Heath recognition.

The work is infused with Heath’s characteristic themes: isolation in an advanced, teeming society; life’s disappointment and pain, with the occasional surprise of joy; the struggle for connection; and reconciling ourselves to what can’t be changed. The exhibit begins with a picture of Philadelphia’s City Hall, Untitled (1948). The building is dwarfed in a canyon of office buildings, pressing in on either side. The William Penn statue is the size of a finger, a vulnerable chess piece. Shot in silhouette and, like all of Heath’s work in this period, black-and-white, the City Hall photo is a symbolic fiction because in 1948 and for decades after, no Philadelphia building was taller.

Another image identified as Mummers Parade (1951) shows a group of blacks, dressed in Sunday clothes, gathered on a stoop. Their faces are blank and turned in different directions, with no particular interest or expectancy. A mother holding a child looks mildly displeased, but the rest seem bored. Even a small boy eating a hot dog doesn’t appear to be enjoying the moment. Though a parade is passing by, like many institutions in the middle of the 20th century, Philadelphia’s Mummers Parade was segregated: This group could do nothing more than stand on the sidewalk and watch. Heath, though white, understood: He was an outsider to the core of his being.

In Rochester, New York (1958), a girl walks alone on a sidewalk, about to pass under a railroad trestle. The image instantly reminded me of Norman Rockwell’s painting The Problem We All Live With (1973), about school desegregation: a small girl walks to school between federal marshals, passing beneath a racial epithet scrawled on the wall.

Forever the outsider

Heath left Philadelphia to serve in the Korean War, where he photographed fellow soldiers and his impressions of war. Soon after his return, he departed for Chicago, where he worked as a photographer’s assistant. He began to assemble handmade books, grouping photos into themed essays and putting text to the images, establishing the template he would use in A Dialogue with Solitude.

Relocating to New York in 1957, Heath studied with photojournalist W. Eugene Smith, refining his photo essay technique and adopting Smith’s practice of making fine art prints of his work. He took photos with available light, in the street and at favorite haunts like Washington Square Park and Seven Arts Coffee Gallery, mounting the Dialogue exhibition in 1963. In that same year, he won his first Guggenheim.

Accepting life on its own terms

When Dialogue went to print in 1965, Heath employed the same editorial control he had with earlier creations, selecting, sizing, and laying out every photo, dictating typeface and size, and selecting text from famous authors, such as William Butler Yeats, Hermann Hesse, and T.S. Eliot. Only in the preface did he use his own words:

“Pressed from all sides by the rapid pace of technological progress and increased authoritarian control, many people are caught up in an anguish of alienation. Adrift and without sense of purpose, they are compelled to engage in a dialogue with the inmost depths of their being in a search for renewal.” He concludes, “What I have endeavored to convey in my work is not a sense of futility. . .but an acceptance. . .that the pleasures and joys of life are fleeting and rare.”

The final sections convey a few of those pleasurable moments: In two photos entitled Chicago (1956), a small boy stands, head thrown back in exultation, and two boys mug for the camera. In Fifth Avenue, New York City (1960), a father snuggles his baby to his face, looking over the child’s head protectively, and in Barbara Freed and Her Son Sean, New York City (1959), a toddler heads toward a pair of outstretched female hands. Heath selected the final excerpt from Eliot’s "Journey of the Magi":

All this was a long time ago, I remember,

And I would do it again, but set down

This set down

This: were we led all that way for

Birth or Death?

What, When, Where

Multitude, Solitude: The Photographs of Dave Heath, through February 21, 2016 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia. 215-763-8100 or philamuseum.org.

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.