Stay in the Loop

BSR publishes on a weekly schedule, with an email newsletter every Wednesday and Thursday morning. There’s no paywall, and subscribing is always free.

A door, a bed, and a toilet

Drawing the imagery of death row

Volunteering in prison as an art teacher is hard, and I often ask myself why continue? But recently, a new student joined my class in a closed-security prison. During class, I mention the through-the-mail art program I teach, which brings art projects to prisoners in solitary confinement nationally. At the end of class, Arthur Tyler, the new student, asks if I know any prisoners on Ohio’s death row. I think of participating prisoners on death row — Armando and Robert on California’s death row and others in various states — but I can’t think of anyone on Ohio’s.

When I draw a blank, Arthur quietly says he has just been released from Ohio’s death row, where he was held for 31 years.

Looking at Arthur, I imagine the freedom he must feel even in a freedom-less place like this high-security prison, leaving the room for the bathroom or drinking from the hallway water fountain. This impact of freedom reminds me of John Berger’s essay, “Mouse Story,” in which the narrator describes a mouse leaping from the cage as only a mouse newly freed can leap; a prisoner realizing his dream of freedom, even if it is only freedom into a high-security prison.

I think of Robert Deninno at Pelican Bay State Prison, California, living in solitary confinement for 10 years. After being released into general population of a maximum-security prison this past August, Robert writes to me, I have been smiling so much that my face hurts. I write back, Robert, You may be the only person who thinks living in a maximum-security prison makes for smiling. But that’s not true; several other men have been released from solitary, and for them, seeing the sky becomes a new experience.

But Arthur is not like Robert or the other men from solitary confinement, now living in general, relieved to feel the sun. When the parole board voted unanimously for his release, Arthur anticipated going home — but Ohio governor John Kasich vetoed this vote. I don’t know why. Some speculate releasing Arthur from prison would interfere with the governor’s re-election campaign. As a presidential candidate, Kasich may again veto Arthur’s next parole hearing in April 2016.

Life on death row

In class, I ask Arthur if art might be a means to explore life on death row. I don’t know what I mean by this question. Yet I know drawing can be an excavation of what is seen, so I ask him to keep a visual journal, drawing whatever comes into his head, like visual free associations.

Usually, I hesitate to ask for words from prisoners. In prison, where language can be misinterpreted and used in parole hearings, writing is reduced to platitudes. Prisoners produce purple prose in which they exchange raw experience for the niceties a public or parole board wants to hear. Regardless, I ask Arthur to write the words that come into his head while drawing.

I tell Arthur something I heard from another prisoner on death row: That despite having no future, this person couldn’t think without a future in his thoughts. This forward thinking is not from spiritual need or hope, but because our existence is ontologically structured with future. Walking down death’s row, we think of a future. Arthur was released to this prison two weeks before his scheduled execution.

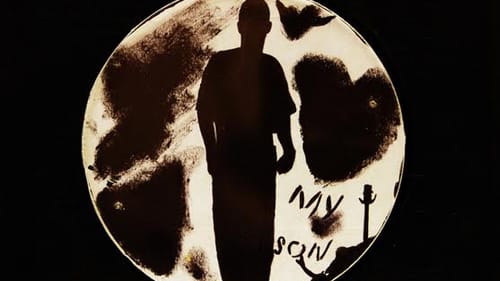

Arthur shows me his drawing and words. There are three images on the paper; a door, a bed, and a toilet — three constant elements of Arthur’s life for 31 years. The words are of hope and survival; sentiments not addressing what either could possibly mean on death row. The words ring of a Hallmark card, albeit one from death row.

“I can only see myself”

I tell Arthur this not to be cruel to his writing but to penetrate beneath the words’ veneer. Arthur looks at the door he has drawn and says, I had no window in the cell; only a door with a small window. And because the window is dark, I can only see myself.

This descriptive analysis is the beginning of what I seek. Not a could-have-been/should-have-been ideal state, but tangible elements upon which meaning is developed through a conversation consisting of a door, a bed, and a toilet.

It is strange that doors are metaphors for opportunity. Most doors are closed, and all doors present a barrier-entrance dichotomy. How does one exist within constant proximity of a locked door? Does the door become a canvas upon which all emotions are projected, thus absorbing the inhabitant’s persona? Or, is it a dark shadow upon the room’s landscape existing with a life of its own in total disregard to the inhabitant?

Life without intimacy

What does a bed say? Does it speak to an intimacy or to a lack? Does it speak to a family or partner long gone?

I don’t know the prisoners’ intimate lives; they don’t tell, and I don’t ask. Once, however, a guard told me, These inmates care more about their bitches in here than their wives. When I asked if this prison intimacy enables compassion that would be missing had the prisoners found no intimacy at all, the guard’s stare tells me my question is stupid, but I am stupider.

Looking at Arthur’s drawing of a death row bed void of any context, I can’t help but wonder how life continues without intimacy; not just sex, but love, hate, frustration, sharing, anxiety, disappointment, joy — feelings demanded in relationship to another person.

What does the toilet suggest? A reminder that no one is self-identical because constant change in daily life flushes away old aspects of self to be exchanged with new? Or that in prison, the plumbing system of change does not work to accommodate a changing self? The prisoner is made to be self-identical, an inmate 24/7. When I ask prisoners if they ever think of themselves not as inmates, the most common answer I get is: When I am sleeping.

I don’t know how these basic elements — a door, a bed, and a toilet — of Arthur’s landscape spoke to him for 31 years. But now that evidence cannot justify Arthur’s years on death row, do they suggest a life wasted?

Sign up for our newsletter

All of the week's new articles, all in one place. Sign up for the free weekly BSR newsletters, and don't miss a conversation.

Treacy Ziegler

Treacy Ziegler